Zero-downtime schema changes: additive migrations that stay safe

Learn zero-downtime schema changes with additive migrations, safe backfills, and phased rollouts that keep older clients working during releases.

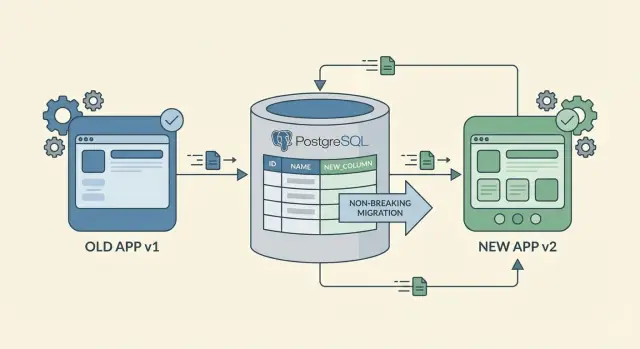

What zero-downtime really means for schema changes

Zero-downtime schema changes don’t mean nothing changes. They mean users can keep working while you update the database and the app, without failures or blocked workflows.

Downtime is any moment your system stops behaving normally. That can look like 500 errors, API timeouts, screens that load but show blank or wrong values, background jobs that crash, or a database that accepts reads but blocks writes because a long migration is holding locks.

A schema change can break more than the main app UI. Common failure points include API clients that expect an old response shape, background jobs that read or write specific columns, reports that query tables directly, third-party integrations, and internal admin scripts that were “working fine yesterday.”

Older mobile apps and cached clients are a frequent problem because you can’t update them instantly. Some users keep an app version for weeks. Others have intermittent connectivity and retry old requests later. Even web clients can behave like “older versions” when a service worker, CDN, or proxy cache holds onto stale code or assumptions.

The real goal isn’t “one big migration that finishes fast.” It’s a sequence of small steps where every step works on its own, even when different clients are on different versions.

A practical definition: you should be able to deploy new code and new schema in any order, and the system still works.

That mindset helps you avoid the classic trap: deploying a new app that expects a new column before the column exists, or deploying a new column that old code can’t handle. Plan changes to be additive first, roll them out in phases, and remove old paths only after you’re sure nothing is using them.

Start with additive changes that don’t break existing code

The safest path to zero-downtime schema changes is to add, not replace. Adding a new column or a new table rarely breaks anything because existing code can keep reading and writing the old shape.

Renames and deletions are the risky moves. A rename is effectively “add new + remove old,” and the “remove old” part is where older clients crash. If you need a rename, treat it as a two-step change: add the new field first, keep the old field for a while, and remove it only after you’re sure nothing depends on it.

When adding columns, start with nullable fields. A nullable column lets old code keep inserting rows without knowing about the new column. If you ultimately want NOT NULL, add it as nullable first, backfill, then enforce NOT NULL later. Defaults can help too, but be careful: adding a default can still touch many rows in some databases, which can slow the change.

Indexes are another “safe but not free” addition. They can make reads faster, but building and maintaining an index can slow writes. Add indexes when you know exactly what query will use them, and consider rolling them out during quieter hours if your database is busy.

A simple rule set for additive database migrations:

- Add new tables or columns first, keep old ones untouched.

- Make new fields optional (nullable) until data is filled.

- Keep old queries and payloads working until clients update.

- Delay constraints (NOT NULL, unique, foreign keys) until after backfills.

Step-by-step rollout plan that keeps old clients working

Treat zero-downtime schema changes as a rollout, not a single deploy. The goal is to let old and new app versions run side by side while the database gradually moves to the new shape.

A practical sequence:

- Add the new schema in a compatible way. Create new columns or tables, allow nulls, and avoid strict constraints that old code can’t satisfy. If you need an index, add it in a way that doesn’t block writes.

- Deploy backend changes that can speak both “languages.” Update the API so it accepts old requests and new requests. Start writing the new field while keeping the old field correct. This “dual write” phase is what makes mixed client versions safe.

- Backfill existing data in small batches. Populate the new column for old rows gradually. Limit batch size, add delays if needed, and track progress so you can pause if load increases.

- Switch reads only after coverage is high. Once most rows are backfilled and you have confidence, change the backend to prefer the new field. Keep a fallback to the old field for a while.

- Remove the old field last, and only when it’s truly unused. Wait until old mobile builds have mostly aged out, logs show no reads of the old field, and you have a clean rollback plan. Then remove the old column and any related code.

Example: you introduce full_name but older clients still send first_name and last_name. For a period, the backend can construct full_name on write, backfill existing users, then later read full_name by default while still supporting older payloads. Only after adoption is clear do you drop the old fields.

Backfills without surprises: how to populate new data safely

A backfill populates a new column or table for existing rows. It’s often the riskiest part of zero-downtime schema changes because it can create heavy database load, long locks, and confusing “half-migrated” behavior.

Start by choosing how you’ll run the backfill. For small datasets, a one-time manual runbook can be fine. For larger datasets, prefer a background worker or scheduled task that can run repeatedly and stop safely.

Batch the work so you control pressure on the database. Don’t update millions of rows in one transaction. Aim for a predictable chunk size and a short pause between batches so normal user traffic stays smooth.

A practical pattern:

- Select a small batch (for example, the next 1,000 rows) using an indexed key.

- Update only what’s missing (avoid re-writing already-backfilled rows).

- Commit quickly, then sleep briefly.

- Record progress (last processed ID or timestamp).

- Retry on failure without starting over.

Make the job restartable. Store a simple progress marker in a dedicated table, and design the job so re-running doesn’t corrupt data. Idempotent updates (for example, update where new_field IS NULL) are your friend.

Validate as you go. Track how many rows are still missing the new value, and add a few sanity checks. For example: no negative balances, timestamps within expected range, status in an allowed set. Spot-check real records by sampling.

Decide what the app should do while the backfill is incomplete. A safe option is fallback reads: if the new field is null, compute or read the old value. Example: you add a new preferred_language column. Until the backfill finishes, the API can return the existing language from profile settings when preferred_language is empty, and only start requiring the new field after completion.

API compatibility rules for mixed client versions

When you ship a schema change, you rarely control every client. Web users update quickly, while older mobile builds can stay active for weeks. That’s why backward compatible APIs matter even if your database migration is “safe.”

Treat new data as optional at first. Add new fields to requests and responses, but don’t require them on day one. If an older client doesn’t send the new field, the server should still accept the request and behave the same way it did yesterday.

Avoid changing the meaning of existing fields. Renaming a field can be fine if you keep the old name working too. Reusing a field for a new meaning is where subtle breakages happen.

Server-side defaults are your safety net. When you introduce a new column like preferred_language, set a default on the server when it’s missing. The API response can include the new field, and older clients should be able to ignore it.

Compatibility rules that prevent most outages:

- Add new fields as optional first, then enforce later after adoption.

- Keep old behavior stable, even if you add a better behavior behind a flag.

- Apply defaults on the server so old clients can omit new fields.

- Assume mixed traffic and test both paths: “new client sends it” and “old client omits it.”

- Keep error messages and error codes stable so monitoring doesn’t suddenly get noisy.

Example: you add company_size to a signup flow. The backend can set a default like “unknown” when the field is missing. Newer clients can send the real value, older clients keep working, and dashboards stay readable.

When your app regenerates: keeping schema and logic in sync

If your platform regenerates the application, you get a clean rebuild of code and configuration. That helps with zero-downtime schema changes because you can make small, additive steps and redeploy often instead of carrying patches for months.

The key is one source of truth. If the database schema changes in one place and business logic changes somewhere else, drift happens fast. Decide where changes are defined, and treat everything else as generated output.

Clear naming reduces accidents during phased rollouts. If you introduce a new field, make it obvious which one is safe for old clients and which one is the new path. For example, naming a new column status_v2 is safer than status_new because it still makes sense six months later.

What to re-test after each regeneration

Even when changes are additive, a rebuild can surface hidden coupling. After every regeneration and deploy, re-check a small set of critical flows:

- Sign up, login, password reset, token refresh.

- Core create and update actions (the ones used most).

- Admin and permission checks.

- Payments and webhooks (for example, Stripe events).

- Notifications and messaging (email/SMS, Telegram).

Plan the migration steps before touching your editor: add the new field, deploy with both fields supported, backfill, switch reads, then retire the old path later. That sequence keeps schema, logic, and generated code moving together so changes stay small, reviewable, and reversible.

Common mistakes that cause outages (and how to avoid them)

Most outages during zero-downtime schema changes aren’t caused by “hard” database work. They come from changing the contract between the database, the API, and clients in the wrong order.

Common traps and safer moves:

- Renaming a column while older code still reads it. Keep the old column, add a new one, and map both for a while (write to both, or use a view). Rename only after you can prove nobody depends on the old name.

- Making a nullable field required too early. Add the column as nullable, ship code that writes it everywhere, backfill old rows, then enforce NOT NULL with a final migration.

- Backfilling in one massive transaction that locks tables. Backfill in small batches, with limits and pauses. Track progress so you can resume safely.

- Switching reads before writes produce the new data. Switch writes first, then backfill, then switch reads. If reads change first, you get empty screens, wrong totals, or “missing field” errors.

- Dropping old fields without proof older clients are gone. Keep old fields longer than you think. Remove only when metrics show older versions are effectively inactive, and you’ve communicated a deprecation window.

If you regenerate your app, it’s tempting to “clean up” names and constraints in one go. Resist that urge. Cleanup is the last step, not the first.

A good rule: if a change can’t be safely rolled forward and rolled back, it isn’t ready for production.

Monitoring and rollback planning for phased migrations

Zero-downtime schema changes succeed or fail on two things: what you watch, and how fast you can stop.

Track signals that reflect real user impact, not just “the deploy finished”:

- API error rate (especially 4xx/5xx spikes on updated endpoints).

- Slow queries (p95 or p99 query time for the tables you touched).

- Write latency (how long inserts and updates take during peak traffic).

- Queue depth (jobs piling up for backfills or event processing).

- Database CPU/IO pressure (any sudden jump after the change).

If you’re doing dual writes (writing both old and new columns or tables), add temporary logging that compares the two. Keep it tight: log only when values differ, include record ID and a short reason code, and sample if volume is high. Create a reminder to remove this logging after the migration so it doesn’t become permanent noise.

Rollback needs to be realistic. Most of the time, you don’t roll back the schema. You roll back the code and keep the additive schema in place.

A practical rollback runbook:

- Revert application logic to the last known good version.

- Disable new reads first, then disable new writes.

- Keep new tables or columns, but stop using them.

- Pause backfills until metrics are stable.

For backfills, build a stop switch you can flip in seconds (feature flag, config value, job pause). Also communicate phases ahead of time: when dual writes start, when backfill runs, when reads switch, and what “stop” looks like so nobody improvises under pressure.

Quick pre-deploy checklist

Right before you ship a schema change, pause and run this quick check. It catches small assumptions that turn into outages with mixed client versions.

- Change is additive, not destructive. The migration adds tables, columns, or indexes only. Nothing is removed, renamed, or made stricter in a way that can reject old writes.

- Reads work with either shape. New server code handles both “new field present” and “new field missing” without errors. Optional values have safe defaults.

- Writes stay compatible. New clients can send new data, old clients can still send old payloads and succeed. If both versions must coexist, the server accepts both formats and produces responses old clients can parse.

- Backfill is safe to stop and start. The job runs in batches, restarts without duplicating or corrupting data, and has a measurable “rows left” number.

- You know the delete date. There’s a concrete rule for when it’s safe to remove legacy fields or logic (for example, after X days plus confirmation that Y% of requests are from updated clients).

If you’re using a regenerating platform, add one more sanity check: generate and deploy a build from the exact model you’re migrating to, then confirm the generated API and business logic still tolerate old records. A common failure is assuming the new schema implies new required logic.

Also write down two quick actions you’ll take if anything looks wrong after deploy: what you’ll monitor (errors, timeouts, backfill progress) and what you’ll roll back first (feature flag off, pause backfill, revert server release). That turns “we’ll react fast” into an actual plan.

Example: adding a new field while older mobile apps are still active

You run an order app. You need a new field, delivery_window, and it will be required for new business rules. The problem is older iOS and Android builds are still in use, and they won’t send that field for days or weeks. If you make the database require it right away, those clients will start failing.

A safe path:

- Phase 1: Add the column as nullable, with no constraints. Keep existing reads and writes unchanged.

- Phase 2: Dual write. New clients (or the backend) write the new field. Older clients keep working because the column allows null.

- Phase 3: Backfill. Populate

delivery_windowfor old rows using a rule (infer from shipping method, or default to “anytime” until the customer edits it). - Phase 4: Switch reads. Update the API and UI to read

delivery_windowfirst, but fall back to the inferred value when it’s missing. - Phase 5: Enforce later. After adoption and backfill are complete, add NOT NULL and remove the fallback.

What users feel during each phase stays boring (that’s the goal):

- Older mobile users can still place orders because the API doesn’t reject missing data.

- New mobile users see the new field, and their choices are saved consistently.

- Support and ops see the field gradually fill in, without sudden gaps.

A simple monitoring gate for each step: track the percentage of new orders where delivery_window is non-null. When it stays consistently high (and validation errors for “missing field” stay near zero), it’s usually safe to move from backfill to enforcing the constraint.

Next steps: build a repeatable migration playbook

A one-off careful rollout isn’t a strategy. Treat schema changes like a routine: same steps, same naming, same sign-offs. Then the next additive change stays boring, even when the app is busy and clients are on different versions.

Keep the playbook short. It should answer: what do we add, how do we ship it safely, and when do we remove the old parts.

A simple template:

- Add only (new column/table/index, new API field that is optional).

- Ship code that can read both old and new shapes.

- Backfill in small batches, with a clear “done” signal.

- Flip behavior with a feature flag or config, not a redeploy.

- Remove old fields/endpoints only after a cutoff date and verification.

Start with a low-risk table (a new optional status, a notes field) and run the full playbook end to end: additive change, backfill, mixed-version clients, then cleanup. That practice run exposes gaps in monitoring, batching, and communication before you attempt a major redesign.

One habit that prevents long-term mess: track “remove later” items like real work. When you add a temporary column, compatibility code, or dual-write logic, create a cleanup ticket immediately with an owner and a date. Keep a small “compatibility debt” note in release docs so it stays visible.

If you build with AppMaster, you can treat regeneration as part of the safety process: model the additive schema, update business logic to handle both old and new fields during the transition, and regenerate so the source code stays clean as requirements change. If you want to see how this workflow fits into a no-code setup that still produces real source code, AppMaster (appmaster.io) is designed around that style of iterative, phased delivery.

The goal isn’t perfection. It’s repeatability: every migration has a plan, a measurement, and an exit ramp. "}

FAQ

Zero-downtime means users can keep working normally while you change the schema and deploy code. That includes avoiding obvious outages, but also avoiding silent breakages like blank screens, wrong values, job crashes, or writes blocked by long locks.

Because many parts of your system depend on the database shape, not just the main UI. Background jobs, reports, admin scripts, integrations, and older mobile apps can still send or expect the old fields long after you deploy new code.

Older mobile builds can stay active for weeks, and some clients retry old requests later. Your API needs to accept both old and new payloads for a while so mixed versions can coexist without errors.

Additive changes usually don’t break existing code because the old schema still exists. Renames and deletions are risky because they remove something old clients still read or write, which turns into crashes or failed requests.

Add the column as nullable first so old code can keep inserting rows. Backfill existing rows in batches, then only after coverage is high and new writes are consistent should you enforce NOT NULL as a final step.

Treat it as a rollout: add compatible schema, deploy code that supports both versions, backfill in small batches, switch reads with a fallback, and remove the old field only when you can prove it’s unused. Each step should be safe on its own.

Run it in small batches with short transactions so you don’t lock tables or spike load. Make it restartable and idempotent by only updating rows that are missing the new value, and track progress so you can pause and resume safely.

Make new fields optional at first and apply defaults on the server when they’re missing. Keep old behavior stable, avoid changing the meaning of existing fields, and test both paths: “new client sends it” and “old client omits it.”

Most of the time you roll back application code, not the schema. Keep the additive columns/tables, disable new reads first, then disable new writes, and pause backfills until metrics stabilize so you can recover quickly without data loss.

Watch user-impact signals like error rates, slow queries, write latency, queue depth, and database CPU/IO after each phase. Move to the next step only when you see steady metrics and high coverage for the new field, then schedule cleanup as real work, not “later.”