Soft delete vs hard delete: choose the right data lifecycle

Soft delete vs hard delete: learn how to keep history, avoid broken references, and still meet privacy deletion requirements with clear rules.

What soft delete and hard delete really mean

“Delete” can mean two very different things. Mixing them up is how teams lose history or fail privacy requests.

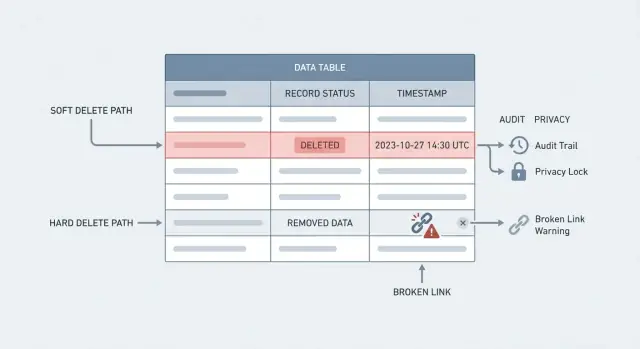

A hard delete is what most people imagine: the row is removed from the database. Query it later and it’s gone. That’s true removal, but it can also break references (like an order that points to a deleted customer) unless you design around it.

A soft delete keeps the row, but marks it as deleted, usually with a field like deleted_at or is_deleted. Your app treats it as gone, but the data is still there for reports, support, and audits.

The tradeoff behind soft delete vs hard delete is simple: history vs true removal. Soft delete protects history and makes “undo” possible. Hard delete reduces what you store, which matters for privacy, security, and legal rules.

Deletes affect more than storage. They change what your team can answer later: a support agent trying to understand a past complaint, finance trying to reconcile billing, or compliance checking who changed what and when. If data disappears too early, reports shift, totals stop matching, and investigations turn into guesswork.

A useful mental model:

- Soft delete hides a record from everyday views but keeps it for traceability.

- Hard delete removes a record permanently and minimizes stored personal data.

- Many real apps use both: keep business records, remove personal identifiers when required.

In practice, you might soft delete a user account to prevent login and keep order history intact, then hard delete (or anonymize) personal fields after a retention period or a verified GDPR right to erasure request.

No tool makes this decision for you. Even if you’re building with a no-code platform like AppMaster, the real work is deciding, per table, what “deleted” means and making sure every screen, report, and API follows the same rule.

The real problems deletes cause in everyday apps

Most teams only notice deletes when something goes wrong. A “simple” delete can erase context, history, and your ability to explain what happened.

Hard deletes are risky because they’re hard to undo. Someone clicks the wrong button, an automated job has a bug, or a support agent follows the wrong playbook. Without clean backups and a clear restore process, that loss becomes permanent, and the business impact shows up fast.

Broken references are the next surprise. You delete a customer, but their orders still exist. Now you have orders pointing at nothing, invoices that can’t show a billing name, and a portal that errors when it tries to load related data. Even with foreign key constraints, the “fix” can be worse: cascading deletes might wipe out far more than you intended.

Analytics and reporting also get messy. When old records disappear, metrics change retroactively. Last month’s conversion rate shifts, lifetime value drops, and trend lines develop gaps nobody can explain. The team starts arguing about numbers instead of making decisions.

Support and compliance are where it hurts most. Customers ask, “Why was I charged?” or “Who changed my plan?” If the record is gone, you can’t reconstruct a timeline. You lose the audit trail that would answer basic questions like what changed, when, and by whom.

Common failure modes behind the soft delete vs hard delete debate:

- Permanent loss from accidental deletes or buggy automation

- Missing parent records that leave children (orders, tickets) orphaned

- Reports that change because historical rows vanish

- Support cases that become unanswerable without history

When soft delete is the better default

Soft delete is usually the safest choice when a record has long-term value or is connected to other data. Instead of removing a row, you mark it as deleted (for example, deleted_at or is_deleted) and hide it from normal views. In a soft delete vs hard delete decision, this default tends to reduce surprises later.

It shines anywhere you need an audit trail in databases. Operations teams often need to answer simple questions like “Who changed this order?” or “Why was this invoice canceled?” If you hard delete too early, you lose evidence that matters for finance, support, and compliance reporting.

Soft delete also makes “undo” possible. Admins can restore a ticket that was closed by mistake, bring back a product that was archived, or recover user-generated content after a false spam report. That kind of restore flow is hard to offer if the data is physically gone.

Relationships are another big reason. Hard deleting a parent row can break foreign key constraints or leave confusing gaps in reports. With soft delete, joins stay stable and historical totals remain consistent (daily revenue, fulfilled orders, response time stats).

Soft delete is a strong default for business records like support tickets, messages, orders, invoices, audit logs, activity history, and user profiles (at least until you confirm final deletion).

Example: a support agent “deletes” an order note that includes a mistake. With soft delete, the note disappears from the normal UI, but supervisors can still review it during a complaint, and finance reports remain explainable.

When hard delete is required

Soft delete is a great default for many apps, but there are times when keeping data (even hidden) is the wrong choice. Hard delete means the record is truly removed, and it’s sometimes the only option that fits legal, security, or cost needs.

The clearest case is privacy and contractual obligations. If a person invokes the GDPR right to erasure, or your contract promises deletion after a set period, “marked as deleted” often doesn’t count. You may need to remove the row, related copies, and any stored identifiers that can point back to the person.

Security is another reason. Some data is too sensitive to keep around: raw access tokens, password reset codes, private keys, one-time verification codes, or unencrypted secrets. Keeping them for history is rarely worth the risk.

Hard delete can also be the right call for scale. If you have massive tables of old events, logs, or telemetry, soft delete quietly grows your database and slows down queries. A planned purge policy keeps the system responsive and costs predictable.

Hard delete is often appropriate for temporary data (caches, sessions, draft imports), short-lived security artifacts (reset tokens, OTPs, invite codes), test/demo accounts, and large historical datasets where only aggregated stats are needed.

A practical approach is to separate “business history” from “personal data.” For example, keep invoices for accounting, but hard-delete (or anonymize) the user profile fields that identify a person.

If your team debates soft delete vs hard delete, use a simple test: if keeping the data creates legal or security risk, hard delete (or irreversible anonymization) should win.

How to model soft delete without surprises

A soft delete works best when it’s boring and predictable. The goal is simple: the record stays in the database, but normal parts of the app act like it’s gone.

Pick one delete signal, and be clear about what it means

You’ll see three common patterns: a deleted_at timestamp, an is_deleted flag, or a status enum. Many teams prefer deleted_at because it answers two questions at once: is it deleted, and when did it happen.

If you already have multiple lifecycle states (active, pending, suspended), a status enum can still work, but keep “deleted” separate from “archived” and “deactivated.” Those are different:

- Deleted: should not appear in normal lists or be usable.

- Archived: kept for history, but still visible in “past” views.

- Deactivated: temporarily disabled, often reversible by the user.

Handle unique fields before they bite you

Soft delete vs hard delete often breaks down on unique fields like email, username, or order number. If a user is “deleted” but their email is still stored and still unique, the same person can’t sign up again.

Two common fixes: either make uniqueness apply only to non-deleted rows, or rewrite the value on delete (for example, append a random suffix). Which you choose depends on privacy and audit needs.

Make filtering rules explicit (and consistent)

Decide what different audiences can see. A common rule set is: regular users never see deleted records, support/admin users can see them with a clear label, and exports/reports include them only when requested.

Don’t rely on “everyone remembers to add the filter.” Put the rule in one place: views, default queries, or your data access layer. If you’re building in AppMaster, that usually means baking the filter into how your endpoints and business processes fetch data, so deleted rows don’t accidentally reappear in a new screen.

Write the meanings down in a short internal note (or schema comments). Future you will thank you when “deleted”, “archived”, and “deactivated” show up in the same meeting.

Keeping references intact: parents, children, and joins

Deletes break apps most often through relationships. A record is rarely alone: users have orders, tickets have comments, projects have files. The tricky part in soft delete vs hard delete is keeping references consistent while still letting the product behave like the item is “gone.”

Foreign keys: choose the failure mode on purpose

Foreign keys protect you from broken references, but each option has a different meaning:

- RESTRICT blocks deletion if children exist.

- SET NULL allows deletion, but detaches children.

- CASCADE deletes children automatically.

- NO ACTION is similar to RESTRICT in many databases, but timing can differ.

If you use soft delete, RESTRICT is often the safest default. You keep the row, so keys stay valid, and you avoid children pointing to nothing.

Soft delete in relationships: hiding without orphaning

Soft delete usually means you don’t change foreign keys. Instead, you filter out deleted parents in the app and in reports. If a customer is soft-deleted, their invoices should still join correctly, but screens shouldn’t show the customer in dropdowns.

For attachments, comments, and activity logs, decide what “delete” means to the user. Some teams keep the shell but remove the risky parts: replace attachment content with a placeholder if privacy requires it, mark comments as from a deleted user (or anonymize the author), and keep activity logs immutable.

Joins and reporting need a clear rule: should deleted rows be included? Many teams keep two standard queries: one “active only” and one “including deleted,” so support and reporting don’t accidentally hide important history.

Step by step: design a data lifecycle that uses both

A practical policy often uses soft delete for day-to-day mistakes and hard delete for legal or privacy needs. If you treat it as one decision (soft delete vs hard delete), you miss the middle ground: keep history for a while, then purge what must go.

A simple 5-part plan

Start by sorting data into a few buckets. “User profile” data is personal, “transactions” are financial records, and “logs” are system history. Each bucket needs different rules.

A short plan that works in most teams:

- Define data groups and owners, and name who approves deletion.

- Set retention and restore rules.

- Decide what gets anonymized instead of removed.

- Add a timed purge step (soft delete now, hard delete later).

- Record an audit event for every delete, restore, and purge (who, when, what, and why).

Make it real with one scenario

Say a customer asks to close their account. Soft delete the user record immediately so they can’t sign in and you don’t break references. Then anonymize personal fields that shouldn’t remain (name, email, phone), while keeping non-personal transaction facts needed for accounting. Finally, a scheduled purge job removes what is still personal after the waiting period.

Common mistakes and traps to avoid

Teams get into trouble not because they chose the wrong approach, but because they apply it unevenly. A common pattern is “soft delete vs hard delete” on paper, but “hide it in one screen and forget the rest” in practice.

One easy mistake: you hide deleted records in the UI, but they still show up through the API, CSV exports, admin tools, or data sync jobs. Users notice quickly when a “deleted” customer appears in an email list or a mobile search result.

Reports and search are another trap. If report queries don’t consistently filter deleted rows, totals drift and dashboards become untrusted. The worst cases are background jobs that re-index or re-send deleted items because they didn’t apply the same rules.

Hard deletes can also go too far. A single cascading delete can wipe orders, invoices, messages, and logs that you actually needed for an audit trail. If you must hard delete, be explicit about what’s allowed to disappear and what must be retained or anonymized.

Unique constraints cause subtle pain with soft delete. If a user deletes their account, then tries to re-sign up with the same email, sign-up can fail if the old row still holds a unique email. Plan for this early.

Compliance teams will ask: can you prove deletion happened, and when? “We think it was deleted” won’t pass many data retention policy reviews. Keep a deletion timestamp, who/what triggered it, and an immutable log entry.

Before you ship, sanity check the full surface area: API, exports, search, reports, and background jobs. Also review cascades table by table, and confirm users can re-create “unique” data like email or username when that’s part of your product promise.

Quick checklist before you ship

Before you pick soft delete vs hard delete, verify the real behavior of your app, not just the schema.

- Restore is safe and predictable. If an admin “undeletes” something, does it return in the right state without reviving data that should stay gone (like revoked access tokens)?

- Queries hide deleted data by default. New screens, exports, and APIs shouldn’t accidentally include deleted rows. Decide on one rule and apply it everywhere.

- References don’t break. Make sure foreign keys and joins can’t produce orphan records or half-empty screens.

- Purge has a schedule and an owner. Soft delete is only half the plan. Define when data is permanently removed, who runs it, and what gets excluded (like active disputes).

- Deletion is logged like any other sensitive action. Record who initiated it, when it happened, and the reason.

Then test the privacy path end to end. Can you fulfill a GDPR right to erasure request across copies, exports, search indexes, analytics tables, and integrations, not just the main database?

A practical way to validate this is to run one “delete user” dry run in staging and follow the data trail.

Example: deleting a user while keeping billing history

A customer writes in: “Please delete my account.” You also have invoices that must remain for accounting and chargeback checks. This is where soft delete vs hard delete becomes practical: you can remove access and personal details while keeping financial records the business must keep.

Separate “the account” from “the billing record.” The account is about login and identity. The billing record is about a transaction that already happened.

A clean approach:

- Soft delete the user account so they can’t sign in and their profile disappears from normal views.

- Keep invoices and payments as active records, but stop tying them to personal fields.

- Anonymize personal data (name, email, phone, address) by replacing it with neutral values like “Deleted User” plus a non-identifying internal reference.

- Hard delete sensitive access items like API tokens, password hashes, sessions, refresh tokens, and remembered devices.

- Keep only what you truly need for compliance and support, and document why.

Support tickets and messages often sit in the middle. If message content includes personal data, you may need to redact parts of the text, remove attachments, and keep the ticket shell (timestamps, category, resolution) for quality tracking. If your product sends messages (email/SMS, Telegram), remove outbound identifiers too, so the person isn’t contacted again.

What can support still see? Usually invoice numbers, dates, amounts, status, and a note that the user was deleted and when. What they can’t see is anything that identifies the person: login email, full name, addresses, saved payment method details, or active sessions.

Next steps: set rules, then implement consistently

Deletion decisions only stick when they’re written down and implemented the same way across the product. Treat soft delete vs hard delete as a policy question first, not a coding trick.

Start with a simple data retention policy anyone on the team can read. It should say what you keep, how long you keep it, and why. “Why” matters because it tells you what wins when two goals clash (for example, support history vs privacy requests).

A good default is often: soft delete for everyday business records (orders, tickets, projects), hard delete for truly sensitive data (tokens, secrets) and anything you shouldn’t retain.

Once the policy is clear, build the flows that enforce it: a “trash” view for restore, a “purge queue” for irreversible deletion after checks, and an audit view showing who did what and when. Make “purge” harder than “delete” so it isn’t used by accident.

If you’re implementing this in AppMaster (appmaster.io), it helps to model soft-delete fields in the Data Designer and centralize delete, restore, and purge logic in one Business Process, so the same rules apply across screens and API endpoints.

FAQ

A hard delete physically removes the row from the database, so future queries can’t find it. A soft delete keeps the row but marks it as deleted (often with deleted_at), so your app hides it in normal screens while preserving history for support, audits, and reporting.

Use soft delete by default for business records you may need to explain later, like orders, invoices, tickets, messages, and account activity. It reduces accidental data loss, keeps relationships intact, and makes a safe “undo” possible without restoring from backups.

Hard delete is best when keeping the data creates privacy or security risk, or when retention rules require true removal. Common examples are password reset tokens, one-time codes, sessions, API tokens, and personal data that must be erased after a verified request or after a retention period.

A deleted_at timestamp is a common choice because it tells you both that the record is deleted and when it happened. It also supports practical workflows like retention windows (purge after 30 days) and audit questions (“when was this removed?”) without needing a separate log just for timing.

Unique fields like email or username often block re-signup if the “deleted” row still holds the unique value. A typical fix is to enforce uniqueness only for non-deleted rows, or to rewrite the unique field during deletion so it no longer collides, depending on your privacy and audit needs.

Hard deleting a parent record can orphan children (like orders) or trigger cascades that delete far more than intended. Soft delete usually avoids broken references because keys stay valid, but you still need consistent filtering so deleted parents don’t appear in dropdowns or user-facing joins.

If you hard delete historical rows, past totals can change, trends can develop gaps, and finance numbers may stop matching what people saw before. Soft delete helps preserve history, but only if reports and analytics queries clearly define whether they include deleted rows and apply that rule consistently.

“Soft deleted” often isn’t enough for right-to-erasure requests because the personal data may still exist in the database and backups. A practical pattern is to remove access immediately, then hard delete or irreversibly anonymize personal identifiers while keeping non-personal transaction facts you must retain for accounting or disputes.

Restoring should bring the record back to a safe, valid state without reviving sensitive items that should stay gone, like sessions or reset tokens. It also needs clear rules for related data, so you don’t restore an account but leave it missing required relationships or permissions.

Centralize delete, restore, and purge behavior so every API, screen, export, and background job applies the same filtering rule. In AppMaster, this is typically done by adding soft-delete fields in the Data Designer and implementing the logic once in a Business Process so new endpoints don’t accidentally expose deleted data.