SLA timers and escalations: maintainable workflow modeling

Learn how to model SLA timers and escalations with clear states, maintainable rules, and simple escalation paths so workflow apps stay easy to change.

Why time-based rules become hard to maintain

Time-based rules usually start simple: “If a ticket has no reply in 2 hours, notify someone.” Then the workflow grows, teams add exceptions, and suddenly nobody is sure what happens when. That’s how SLA timers and escalations turn into a maze.

It helps to name the moving parts clearly.

A timer is the clock you start (or schedule) after an event, like “ticket moved to Waiting for Agent.” An escalation is what you do when that clock hits a threshold, like notifying a lead, changing priority, or reassigning work. A breach is the recorded fact that says, “We missed the SLA,” which you use for reporting, alerts, and follow-up.

Problems show up when time logic is scattered across the app: a few checks in the “update ticket” flow, more checks in a nightly job, and one-off rules added later for a special customer. Each piece makes sense on its own, but together they create surprises.

Typical symptoms:

- The same time calculation gets copied into multiple flows, and fixes don’t reach every copy.

- Edge cases get missed (pause, resume, reassignment, status toggles, weekends vs working hours).

- A rule triggers twice because two paths schedule similar timers.

- Auditing becomes guesswork: you can’t answer “why did this escalate?” without reading the whole app.

- Small changes feel risky, so teams add exceptions instead of fixing the model.

The goal is predictable behavior that stays easy to change later: one clear source of truth for SLA timing, explicit breach states you can report on, and escalation steps you can adjust without hunting through visual logic.

Start by defining the SLA you actually need

Before you build any timers, write down the exact promise you’re measuring. A lot of messy logic comes from trying to cover every possible time rule from day one.

Common SLA types sound similar but measure different things:

- First response: time until a human sends the first meaningful reply.

- Resolution: time until the issue is truly closed.

- Waiting on customer: time you don’t want to count while you’re blocked.

- Internal handoff: time a ticket can sit in a specific queue.

- Reopen SLA: what happens when a “closed” item comes back.

Next, decide what “time” means. Calendar time counts 24/7. Working time counts only defined business hours (for example, Mon-Fri, 9-6). If you don’t truly need working time, avoid it early on. It adds edge cases like holidays, time zones, and partial days.

Then get specific about pauses. A pause isn’t just “status changed.” It’s a rule with an owner. Who can pause it (agent only, system only, customer action)? Which statuses pause it (Waiting on Customer, On Hold, Pending Approval)? What resumes it? When it resumes, do you continue from the remaining time or restart the timer?

Finally, define what a breach means in product terms. A breach should be a concrete thing you can store and query, such as:

- a breach flag (true/false)

- a breach timestamp (when the deadline was missed)

- a breach state (Approaching, Breached, Resolved after breach)

Example: “First response SLA breached” might mean the ticket gets a Breached state, a breached_at timestamp, and an escalation level set to 1.

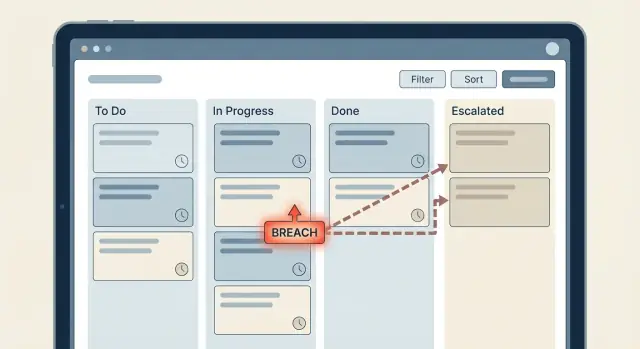

Model SLA as explicit states, not scattered conditions

If you want SLA timers and escalations to stay readable, treat SLA like a small state machine. When the “truth” is spread across tiny checks (if now > due, if priority is high, if last reply is empty), visual logic gets messy fast and small changes break things.

Start with a short, agreed set of SLA states that every workflow step can understand. For many teams, these cover most cases:

- On track

- Warning

- Breached

- Paused

- Completed

A single breached = true/false flag is rarely enough. You still need to know which SLA breached (first response vs resolution), whether it’s currently paused, and whether you already escalated. Without that context, people start re-deriving meaning from comments, timestamps, and status names. That’s where logic becomes fragile.

Make the state explicit and store the timestamps that explain it. Then decisions stay simple: your evaluator reads the record, decides the next state, and everything else reacts to that state.

Useful fields to store alongside the state:

started_atanddue_at(what clock are we running, and when is it due?)breached_at(when did it actually cross the line?)paused_atandpaused_reason(why did the clock stop?)breach_reason(which rule triggered the breach, in plain words)last_escalation_level(so you don’t notify the same level twice)

Example: a ticket moves to “Waiting on customer.” Set SLA state to Paused, record paused_reason = "waiting_on_customer", and stop the timer. When the customer replies, resume by setting a new started_at (or unpausing and recalculating due_at). No hunting through many conditions.

Design an escalation ladder that fits your org

An escalation ladder is a clear plan for what happens when an SLA timer is close to breaching or has breached. The mistake is copying the org chart into the workflow. You want the smallest set of steps that gets a stalled item moving again.

A simple ladder many teams use: the assigned agent (Level 0) gets the first nudge, then the team lead (Level 1) is pulled in, and only after that does it go to a manager (Level 2). It works because it starts where the work can actually be done, and it escalates authority only when needed.

To keep workflow escalation rules maintainable, store escalation thresholds as data, not hardcoded conditions. Put them in a table or settings object: “first reminder after 30 minutes” or “escalate to lead after 2 hours.” When policies change, you update one place instead of editing multiple workflows.

Keep escalations helpful, not noisy

Escalations turn into spam when they fire too often. Add guardrails so each step has a purpose:

- A retry rule (for example, resend to Level 0 once if no action happens).

- A cooldown window (for example, don’t send any escalation notifications for 60 minutes after one is sent).

- A stop condition (cancel future escalations as soon as the item moves to a compliant status).

- A max level (don’t go beyond Level 2 unless a human manually triggers it).

Decide who owns the item after escalation

Notifications alone don’t fix stalled work if responsibility stays fuzzy. Define ownership rules up front: does the ticket remain assigned to the agent, get reassigned to the lead, or move to a shared queue?

Example: after Level 1 escalation, reassign to the team lead and set the original agent as a watcher. That makes it obvious who must act next and prevents the ladder from bouncing the same item between people.

A maintainable pattern: events, evaluator, actions

The easiest way to keep SLA timers and escalations maintainable is to treat them like a small system with three parts: events, an evaluator, and actions. This keeps time logic from spreading across dozens of “if time > X” checks.

1) Events: only record what happened

Events are simple facts that shouldn’t contain timer math. They answer “what changed?” not “what should we do about it?” Typical events include ticket created, agent replied, customer replied, status changed, or a manual pause/resume.

Store these as timestamps and status fields (for example: created_at, last_agent_reply_at, last_customer_reply_at, status, paused_at).

2) Evaluator: one place that computes time and sets state

Make a single “SLA evaluator” step that runs after any event and on a periodic schedule. This evaluator is the only place that computes due_at and remaining time. It reads the current facts, recalculates deadlines, and writes explicit SLA state fields like sla_response_state and sla_resolution_state.

This is where breach state modeling stays clean: the evaluator sets states such as OK, AtRisk, Breached, instead of hiding logic inside notifications.

3) Actions: react to state changes, not time math

Notifications, assignments, and escalations should trigger only when a state changes (for example: OK -> AtRisk). Keep sending messages separate from updating SLA state. Then you can change who gets notified without touching calculations.

Step by step: build timers and escalations in visual logic

A maintainable setup usually looks like this: a few fields on the record, a small policy table, and one evaluator that decides what happens next.

1) Set up data so time logic has one home

Start with the entity that owns the SLA (ticket, order, request). Add explicit timestamps and a single “current SLA state” field. Keep it boring and predictable.

Then add a small policy table that describes rules instead of hardcoding them into many flows. A simple version is one row per priority (P1, P2, P3) with columns for target minutes and escalation thresholds (for example: warn at 80%, breach at 100%). This is the difference between changing one record versus editing five workflows.

2) Run a scheduled evaluator, not dozens of timers

Instead of creating separate timers everywhere, use one scheduled process that checks items periodically (every minute for strict SLAs, every 5 minutes for many teams). The schedule calls one evaluator that:

- selects records that are still active (not closed)

- calculates “now vs due” and derives the next state

- computes the next escalation moment (so you can skip re-checking too often)

- writes back

sla_stateandnext_check_at

This makes SLA timers and escalations easier to reason about because you debug one evaluator, not many timers.

3) Make actions edge-triggered (only on change)

The evaluator should output both the new state and whether it changed. Only fire messages or tasks when the state moves (for example ok -> warning, warning -> breached). If the record stays breached for an hour, you don’t want 12 repeated notifications.

A practical pattern is: store sla_state and last_escalation_level, compare them to newly computed values, and only then call messaging (email/SMS/Telegram) or create an internal task.

Handling pauses, resumes, and status changes

Pauses are where time rules usually get messy. If you don’t model them clearly, your SLA will either keep running when it shouldn’t, or reset when someone clicks the wrong status.

A simple rule: only one status (or a small set) pauses the clock. A common choice is Waiting for customer. When a ticket moves into that status, store a pause_started_at timestamp. When the customer replies and the ticket leaves that status, close the pause by writing a pause_ended_at timestamp and adding the duration to paused_total_seconds.

Don’t just keep a single counter. Capture each pause window (start, end, who or what triggered it) so you have an audit trail. Later, when someone asks why a case breached, you can show that it spent 19 hours waiting on the customer.

Reassignment and normal status changes shouldn’t restart the clock. Keep SLA timestamps separate from ownership fields. For example, sla_started_at and sla_due_at should be set once (on creation, or when SLA policy changes), while reassignment only updates assignee_id. Your evaluator can then compute elapsed time as: now minus sla_started_at minus paused_total_seconds.

Rules that keep SLA timers and escalations predictable:

- Pause only on explicit statuses (like Waiting for customer), not on soft flags.

- Resume only when leaving that status, not on any inbound message.

- Never reset SLA on reassignment; treat it as routing, not a new case.

- Allow manual overrides, but require a reason and limit who can do it.

- Log every status change and pause window.

Example scenario: support ticket with response and resolution SLAs

A simple way to test your design is a support ticket with two SLAs: first response in 30 minutes, and full resolution in 8 hours. This is where logic often breaks if it’s spread across screens and buttons.

Assume each ticket stores: state (New, InProgress, WaitingOnCustomer, Resolved), response_status (Pending, Warning, Breached, Met), resolution_status (Pending, Warning, Breached, Met), plus timestamps like created_at, first_agent_reply_at, and resolved_at.

A realistic timeline:

- 09:00 Ticket created (New). Response timer and resolution timer start.

- 09:10 Assigned to Agent A (still Pending for both SLAs).

- 09:25 No agent reply yet. Response hits 25 minutes and flips to Warning.

- 09:40 Still no reply. Response hits 30 minutes and flips to Breached.

- 09:45 Agent replies. Response becomes Met (even if it was Breached, keep the breach record and mark Met for reporting).

- 10:30 Customer replies with more info. Ticket goes to InProgress, resolution continues.

- 11:00 Agent asks a question. Ticket goes to WaitingOnCustomer and resolution timer pauses.

- 14:00 Customer responds. Ticket returns to InProgress and resolution timer resumes.

- 16:30 Ticket resolved. Resolution becomes Met if total active time is under 8 hours, otherwise Breached.

For escalations, keep one clear chain that triggers on state transitions. For example, when response becomes Warning, notify the assigned agent. When it becomes Breached, notify the team lead and update priority.

At each step, update the same small set of fields so it stays easy to reason about:

- Set

response_statusorresolution_statusto Pending, Warning, Breached, or Met. - Write

*_warning_atand*_breach_attimestamps once, then never overwrite them. - Increment

escalation_level(0, 1, 2) and setescalated_to(Agent, Lead, Manager). - Add an

sla_eventslog row with the event type and who was notified. - If needed, set

priorityanddue_atso the UI and reports reflect the escalation.

The key is that Warning and Breached are explicit states. You can see them in data, audit them, and change the ladder later without hunting down hidden timer checks.

Common traps and how to avoid them

SLA logic gets messy when it spreads. A quick time check added to a button here, a conditional alert there, and soon nobody can explain why a ticket escalated. Keep SLA timers and escalations as a small, central piece of logic that every screen and action relies on.

A common trap is embedding time checks in many places (UI screens, API handlers, manual actions). The fix is to compute SLA status in one evaluator and store the result on the record. Screens should read status, not invent it.

Another trap is letting timers disagree because they use different clocks. If the browser calculates “minutes since created” but the backend uses server time, you’ll see edge cases around sleep, time zones, and daylight changes. Prefer server time for anything that triggers an escalation.

Notifications can also get noisy fast. If you “check every minute and send if overdue,” people may get spammed every minute. Tie messages to transitions instead: “warning sent,” “escalated,” “breached.” Then you send once per step and can audit what happened.

Business hours logic is another source of accidental complexity. If every rule has its own “if weekend then…” branch, updates become painful. Put business-hours math in one function (or one shared block) that returns “SLA minutes consumed so far,” and reuse it.

Finally, don’t rely on recomputing breach from scratch. Store the moment it happened:

- Save

breached_atthe first time you detect a breach, and never overwrite it. - Save

escalation_levelandlast_escalated_atso actions are idempotent. - Save

notified_warning_at(or similar) to prevent repeated alerts.

Example: a ticket hits “Response SLA breached” at 10:07. If you only recompute, a later status change or a pause/resume bug can make it look like the breach happened at 10:42. With breached_at = 10:07, reporting and postmortems stay consistent.

Quick checklist for maintainable SLA logic

Before you add timers and alerts, do one pass with the goal of making the rules readable a month from now.

- Every SLA has clear boundaries. Write down the exact start event, stop event, pause rules, and what counts as a breach. If you can’t point to one event that starts the clock, your logic will spread into random conditions.

- Escalations are a ladder, not a pile of alerts. For each escalation level, define the threshold (like 30m, 2h, 1d), who gets it, a cooldown (so you don’t spam), and the maximum level.

- State changes are logged with context. When an SLA state changes (Running, Paused, Breached, Resolved), store who triggered it, when it happened, and why.

- Scheduled checks are safe to run twice. Your evaluator should be idempotent: if it runs again for the same record, it shouldn’t create duplicate escalations or re-send the same message.

- Notifications come from transitions, not raw time math. Send alerts when the state changes, not when “now - created_at > X” is true.

A practical test: pick one ticket that’s close to breaching and replay its timeline. If you can’t explain what will happen at each status change without reading the whole workflow, your model is too scattered.

Next steps: implement, observe, then refine

Build the smallest useful slice first. Pick one SLA (for example, first response) and one escalation level (for example, notify the team lead). You’ll learn more from a week of real usage than from a perfect design on paper.

Keep thresholds and recipients as data, not logic. Put minutes and hours, business-hours rules, who gets notified, and which queue owns the case into tables or config records. Then the workflow stays stable while the business tweaks numbers and routing.

Plan a simple dashboard view early. You don’t need a big analytics system, just a shared picture of what’s happening right now: on track, warning, breached, escalated.

If you’re building this in a no-code workflow app, it helps to choose a platform that lets you model data, logic, and scheduled evaluators in one place. For example, AppMaster (appmaster.io) supports database modeling, visual business processes, and generating production-ready apps, which fits well with the “events, evaluator, actions” pattern.

Refine safely by iterating in this order:

- Add one more escalation level only after Level 1 behaves well

- Expand from one SLA to two (response and resolution)

- Add pause/resume rules (waiting on customer, on hold)

- Tighten notifications (dedupe, quiet hours, correct recipients)

- Review weekly: adjust thresholds in data, not by rewiring the flow

When you’re ready, build a small version first, then grow it with real feedback and real tickets.

FAQ

Start with a clear definition of the promise you’re measuring, like first response or resolution, and write down the exact start, stop, and pause rules. Then centralize the time math in one evaluator that sets explicit SLA states instead of sprinkling “if now > X” checks across many workflows.

A timer is the clock you start or schedule after an event, such as a ticket moving to a new status. An escalation is the action you take when a threshold is reached, like notifying a lead or changing priority. A breach is the stored fact that the SLA was missed, which you can report on later.

First response measures time until the first meaningful human reply, while resolution measures time until the issue is truly closed. They behave differently around pauses and reopenings, so modeling them separately keeps your rules simpler and your reporting accurate.

Use calendar time by default because it’s simpler and easier to debug. Only add working-time rules if you truly need them, since business hours introduce extra complexity like holidays, time zones, and partial-day calculations.

Model pauses as explicit states tied to specific statuses, like Waiting on Customer, and store when the pause started and ended. When you resume, either continue with remaining time or recalculate due time in one place, but don’t let random status toggles reset the clock.

A single flag hides important context, like which SLA breached, whether it’s paused, and whether you already escalated. Explicit states like On track, Warning, Breached, Paused, and Completed make the system predictable and easier to audit and change.

Store timestamps that explain the state, such as started_at, due_at, breached_at, and pause fields like paused_at and paused_reason. Also store escalation tracking like last_escalation_level so you don’t notify the same level twice.

Create a small ladder that starts with the person who can act, then escalates to a lead, then a manager only if needed. Keep thresholds and recipients as data (like a policy table) so changing escalation timing doesn’t require editing multiple workflows.

Tie notifications to state transitions like OK -> Warning or Warning -> Breached, not to “still overdue” checks. Add simple guardrails like cooldown windows and stop conditions so you send one message per step instead of repeating alerts every scheduled run.

Use a pattern of events, a single evaluator, and actions: events record facts, the evaluator computes deadlines and sets SLA state, and actions react only to state changes. In AppMaster, you can model the data, build the evaluator as a visual business process, and trigger notifications or assignments from the state updates while keeping time math centralized.