Secrets and configuration management for dev, staging, prod

Learn secrets and configuration management across dev, staging, and prod with simple patterns for API keys, SMTP creds, and webhook secrets without leaks.

What problem we are solving

Secrets and configuration management is about keeping sensitive values out of places where they can be copied, cached, or shared by accident.

A secret is anything that grants access or proves identity, like an API key, a database password, an SMTP login, or a webhook signing secret. Normal config is a value that can be public without harm, like a feature flag name, a timeout, or a base URL for a public site.

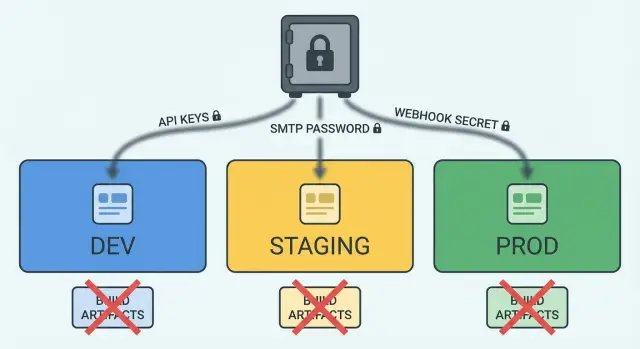

Dev, staging, and prod need different values because they serve different goals. Dev is for fast iteration and safe testing. Staging should look like prod but stay isolated. Prod must be locked down, auditable, and stable. If you reuse the same secrets everywhere, one leak in dev can turn into a breach in prod.

“Leaking into builds” means a secret becomes part of something that gets packaged and shared, such as a compiled backend binary, a mobile app bundle, or a front-end bundle. Once a secret is in a build artifact, it can spread to places you don’t control.

Accidental leaks usually happen through a few predictable paths:

- Hardcoding secrets in source code, samples, or comments

- Committing a local

.envfile or config export to a repo - Baking secrets into front-end or mobile builds that run on user devices

- Printing secrets in logs, crash reports, or build output

- Copying production values into staging “just for a quick test”

A simple example: a developer adds an SMTP password to a config file to “get email working,” then the file gets committed or packaged into a release build. Even if you rotate the password later, the old build may still be sitting in a CI cache, an app store upload, or someone’s download folder.

The goal is straightforward: keep secrets outside code and builds, and inject the right values per environment at runtime or through a secure deployment step.

Basic principles that prevent most leaks

Most of the safety here comes from a few habits you follow every time.

Keep secrets out of code and build outputs. Code spreads. It gets copied, reviewed, logged, cached, and uploaded. Builds spread too: artifacts can end up in CI logs, app bundles, container registries, or shared folders. Treat anything that gets committed or compiled as public.

Separate credentials per environment (least privilege). Your dev key should only work in dev, and it should be limited in what it can do. If a key leaks from a laptop or test server, the damage stays contained. The same idea applies to SMTP users, database passwords, and webhook signing secrets.

Make rotation boring. Assume you will rotate secrets, because you will. Design so you can replace a value without editing code and without rebuilding every app. For many systems, that means reading secrets at runtime (from environment variables or a secret store) and supporting more than one active secret during a transition.

Limit and log access. Secrets should be readable only by the service that needs them, and only in the environment where it runs. Human access should be rare, time-limited, and auditable.

If you want a small rule set that covers most cases:

- Don’t commit secrets or paste them into tickets, chats, or screenshots.

- Use separate credentials for dev, staging, and prod.

- Prefer runtime config over baking values into images or mobile builds.

- Rotate on a schedule and after any suspected exposure.

- Restrict who and what can read secrets, and keep access logs.

These principles apply whether you’re using a traditional code stack or a no-code platform like AppMaster. The safer path is the same: keep secrets outside the build and tightly scoped to where they’re used.

Where secrets leak from most often

Most leaks aren’t “hacks.” They happen during normal work: a quick test, a helpful screenshot, a build that prints too much. A good starting point is knowing where those small slips usually occur.

Source control is the classic one. Someone pastes an API key into a config file “just for now,” commits it, and it spreads through branches, pull requests, and code review comments. Even if you remove it later, the secret can live forever in history or in a copied patch.

Anything you ship to users is another major leak source. Front-end bundles and mobile app binaries are easy to inspect. If a secret is in JavaScript, an iOS/Android app, or a “baked” config, assume it’s public. Client apps can hold public identifiers, but not private keys.

Secrets also leak through “helpful noise” in automation and support. Common examples include CI logs that echo environment variables, debug prints that include SMTP credentials, crash reports that capture configuration and outbound requests, container images and build caches that accidentally store .env files, and support tickets with copied logs or screenshots of settings pages.

A common pattern is a secret entering the build pipeline once, then getting copied everywhere: into a container layer, into a cached artifact, into a log, and into a ticket. The fix is rarely just one tool. It’s a habit: keep secrets out of code, out of builds, and out of anything humans paste into chat.

Common secret types and their risks

It helps to know what kind of secret you’re dealing with, what it can do if it leaks, and where it must never appear.

API keys (Stripe, maps, analytics, and other services) are often “project level” credentials. They identify your app and allow specific actions, like charging a card or reading usage stats. They’re not the same as user tokens. Tokens represent a specific user session and should expire. Many API keys don’t expire on their own, which makes leaks more damaging.

SMTP credentials are usually a username and password for an email server. If those leak, an attacker can send spam from your domain and ruin deliverability. API-based email providers replace raw SMTP passwords with API keys and scoped permissions, which can be safer, but the risk stays high if the key can send email from your account.

Webhook secrets (signing secrets or verification keys) protect inbound requests. If the signing secret leaks, someone can forge “payment succeeded” or “subscription canceled” events and trick your system. The danger isn’t just data exposure. It’s business logic being executed on fake events.

Other high-impact secrets include database URLs (often with embedded passwords), service account credentials, and encryption keys. A leaked database URL can mean full data theft. A leaked encryption key can make past and future data readable, and rotation can be painful.

A quick way to think about impact:

- Can spend money or trigger actions: payments keys, admin API keys, webhook signing secrets

- Can impersonate you: SMTP passwords, email sending keys, messaging bot tokens

- Can expose all data: database credentials, cloud service accounts

- Can break privacy permanently: encryption keys, signing keys

- Often safe to ship: publishable keys meant for the browser (still restrict by domain/app)

Never ship these to client apps (web, iOS, Android): secret API keys, SMTP credentials, database passwords, service accounts, private encryption keys, and webhook signing secrets. If a client needs to call a third-party API, route it through your backend so the secret stays server-side.

Patterns for storing secrets without putting them in builds

A safe default is simple: don’t bake secrets into anything that gets compiled, exported, or shared. Treat builds as public artifacts, even if you think they’re private.

Choose the right container for each environment

For local development, a config file can be fine if it stays out of version control and is easy to replace (for example, a local-only .env style file). For staging and production, prefer a real secret store: your cloud provider’s secret manager, a dedicated vault, or your platform’s protected environment settings.

Environment variables are a good default because they’re easy to inject at runtime and keep separate from the codebase. The key detail is timing: runtime injection is safer than build-time injection because the secret never becomes part of the build output or client bundle.

A practical split that works for many teams:

- Local dev: local env vars or a local secrets file, unique per developer machine

- Staging: a secret manager or protected environment settings, scoped to staging only

- Production: a secret manager with stricter access controls, audit logs, and rotation

Keep naming and boundaries consistent

Use the same key names in every environment so the app behaves the same: SMTP_HOST, SMTP_USER, SMTP_PASS, STRIPE_SECRET_KEY, WEBHOOK_SIGNING_SECRET. Only the values change.

When environments start to matter (payments, email, webhooks), use separate projects or cloud accounts per environment when possible. For example, keep staging Stripe keys and webhook secrets in a staging-only store so a staging mistake can’t touch production.

If you deploy with a platform like AppMaster, prefer runtime environment settings for backend services so secrets stay server-side and aren’t embedded into exported code or client apps.

Step by step setup across dev, staging, and prod

Make it hard to misuse secrets by default.

-

Inventory what you have and where it’s used. Include API keys, SMTP usernames and passwords, webhook signing secrets, database passwords, JWT signing keys, and third-party tokens. For each one, note the owner (team or vendor), the component that reads it (backend, worker, mobile, web), and how often it could realistically be rotated.

-

Create separate values for dev, staging, and prod, plus separate permissions. Dev secrets should be safe to use from laptops and local containers. Staging should look like prod, but never share prod credentials or accounts. Prod should be readable only by the production runtime identity, not by humans by default.

-

Move secrets to runtime configuration, not build time. If a secret is present during a build, it can end up in build logs, Docker layers, client bundles, or crash reports. The simple rule: builds produce artifacts that are safe to copy around; secrets are injected only when the app starts.

-

Use a consistent deployment flow. One approach that keeps teams out of trouble:

- Create one secret store per environment (or a strict namespace per environment).

- Give the application runtime identity read access only to its own environment secrets.

- Inject secrets at startup via environment variables or mounted files, and keep them out of images and front-end bundles.

- Add rotation rules (expiry dates, owner, and a reminder cadence) for every secret.

- Add a hard test: staging deployments must fail if they ever try to read a prod secret.

Lockdown mostly means reducing who and what can read each secret. Avoid shared accounts, avoid long-lived tokens where possible, and keep read permissions narrower than write permissions.

If you use a no-code platform like AppMaster, the same approach holds up: keep third-party credentials in environment-specific runtime settings, and treat generated build artifacts as public inside your team. That single decision prevents a lot of accidental leaks.

Practical patterns for API keys and SMTP credentials

Many leaks happen when an app needs to “send something” and the quickest fix is to paste credentials into the client or into a config file that gets bundled into a build. A good default rule is simple: web and mobile clients should never hold SMTP usernames, SMTP passwords, or provider keys that can send messages.

For email, prefer an email provider’s API key over raw SMTP when you can. API-based sending is easier to scope (only send mail, nothing else), rotate, and monitor. If you must use SMTP, keep it server-side only and make the backend the single place that talks to the mail server.

A practical setup that stays safe:

- Put email sending behind a backend endpoint (for example: “send password reset” or “send invoice”).

- Store the API key or SMTP password as an environment secret on the backend, not in source code or UI settings.

- Use separate credentials for dev, staging, and prod (ideally separate accounts and sender domains).

- Add a staging recipient allowlist so only approved addresses can receive mail.

- Log delivery results (message ID, provider response, recipient domain) but never log credentials or full message bodies.

Separation between staging and prod matters more than people think. A staging system can accidentally spam real customers if it shares the same sender and recipient rules. A simple guard is: in staging, block all outbound email unless the recipient is on an allowlist (for example, your team’s addresses).

Example: you build a customer portal in AppMaster. The mobile app triggers “email me a login code.” The app calls your backend, the backend reads the prod or staging mail secret from its environment, and sends the email. If a tester uses staging, the allowlist prevents messages to real customers, and your logs still show whether the send succeeded without exposing the key.

Webhook secrets: signing, verification, and rotation

Webhook security comes down to one rule: verify every request on the server with a secret that never leaves your backend. If a secret ships to a web or mobile app, it’s no longer a secret.

Signing and verification

Treat a webhook like an incoming card payment: accept nothing until it’s verified. The provider sends a signature header computed from the payload and your shared secret. Your server recomputes the signature and compares it.

A simple verification flow:

- Read the raw request body exactly as received (no reformatting).

- Compute the expected signature using your webhook secret.

- Compare using constant-time comparison.

- Reject missing or invalid signatures with a clear 401 or 403.

- Only then parse JSON and process the event.

Use separate webhook endpoints and separate secrets for dev, staging, and prod. This prevents a dev tool or test system from triggering prod actions, and it makes incidents easier to contain. In AppMaster, that usually means different environment configs for each deployment, with the webhook secret stored as a server-side variable, not in the web or mobile UI.

Replay protection and rotation

Signatures stop tampering, but they don’t automatically stop replay. Add checks that make each request valid only once, or only for a short time window. Common options include a timestamp header with a strict time limit, a nonce, or an idempotency key you store and refuse to process twice.

Plan rotation before you need it. A safe pattern is to support two active secrets for a short overlap: accept either secret for verification while you update the provider, then retire the old one. Keep a clear cutoff time and monitor for old-signature traffic.

Finally, be careful with logs. Webhook payloads often include emails, addresses, or payment metadata. Log event IDs, types, and verification results, but avoid printing full payloads or headers that could expose sensitive data.

Common mistakes and traps to avoid

Most leaks are simple habits that feel convenient during development, then get copied into staging and production.

Treating a local .env file like a safe place forever is a common slip. It’s fine for your laptop, but it becomes dangerous the moment it gets copied into a repo, a shared zip, or a Docker image. If you use .env, make sure it’s ignored by version control and replaced by environment settings in real deployments.

Using the same credentials everywhere is another frequent problem. A single API key reused across dev, staging, and prod means any mistake in dev can become a production incident. Separate keys also make it easier to rotate, revoke, and audit access.

Injecting secrets at build time for web frontends and mobile apps is especially risky. If a secret ends up inside a compiled bundle or an app package, assume it can be extracted. Frontends should receive only public configuration (like a base API URL). Anything sensitive must stay on the server.

Logs are a quiet leak source. A “temporary” debug print can live for months and get shipped. If you need to confirm a value, log only a masked version (for example, the last 4 characters) and remove the statement right away.

Red flags that usually mean trouble

- Secrets appear in Git history, even if later removed.

- One key works in every environment.

- A mobile app contains vendor keys or SMTP passwords.

- Support tickets include full request dumps with headers.

- Values are “hidden” with base64 or in form fields.

Encoding isn’t protection, and hidden fields are still visible to users.

If you’re building with AppMaster, keep sensitive values in environment-level configuration for each deployment target (dev, staging, prod) and pass only non-sensitive settings into client apps. A quick reality check: if the browser can see it, treat it as public.

Quick checklist before you ship

Do a final pass with a “what could leak” mindset. Most incidents are boring: a key pasted into a ticket, a screenshot with a config panel, or a build artifact that quietly includes a secret.

Before you ship, verify these basics:

- Secrets aren’t in your repo history, issues, docs, screenshots, or chat logs. If you ever pasted one, assume it’s compromised and rotate it.

- Your web and mobile builds contain only public settings (like API base URLs or feature flags). Private keys, SMTP passwords, and webhook signing secrets must live server-side or in environment-specific secret stores.

- Staging is isolated from production. It should use its own API keys, its own SMTP account, and test payment/webhook endpoints. Staging should not be able to read prod databases or prod secret managers.

- CI logs, monitoring, and error reports don’t print sensitive values. Check build output, crash reports, and debug logging. Mask tokens and redact headers like

Authorization. - You can rotate and revoke fast without code changes. Make sure secrets are injected at deploy time (environment variables or a secret manager), so a key change is a configuration update, not an emergency rebuild.

If you’re using AppMaster, treat secrets as deployment-time configuration for each environment, not as values baked into UI screens or exported builds. A useful last check is to search compiled artifacts and logs for common patterns like sk_live, Bearer , or SMTP hostnames.

Write down the “kill switch” for each integration: where you disable the key, and who can do it in under five minutes.

Example scenario: payments, email, and webhooks

A three-person team runs a customer portal (web), a companion mobile app, and a small background job that sends receipts and syncs data. They have three environments: dev on laptops, staging for QA, and prod for real users. They want a secrets and configuration setup that doesn’t slow down daily work.

In dev, they only use sandbox payment keys and a test SMTP account. Each developer keeps secrets in local environment variables (or a local untracked file loaded into env vars), so nothing lands in the repo. The web app, mobile app, and background job all read the same variable names, like PAYMENTS_KEY, SMTP_USER, and WEBHOOK_SECRET, but the values differ per environment.

In staging, CI deploys the build, and the platform injects secrets at runtime. Staging uses its own payment account, its own SMTP credentials, and its own webhook signing secret. QA can test real flows without any chance of hitting prod systems.

In prod, the same build artifacts get deployed, but secrets come from a dedicated secrets store (or the cloud provider’s secret manager) and are only available to the running services. The team also sets tighter permissions so only the background job can read SMTP credentials, and only the webhook handler can read the webhook secret.

When a key is exposed (for example, a screenshot shows an API key), they follow a fixed playbook:

- Revoke the exposed key immediately and rotate related secrets.

- Search logs for suspicious use during the exposure window.

- Redeploy services to pick up the new values.

- Document what happened and add a guardrail (like a pre-commit scan).

To keep local work easy, they never share prod secrets. Devs use sandbox accounts, and if they use a no-code tool like AppMaster, they store separate environment values for dev, staging, and prod so the same app logic runs safely everywhere.

Next steps: make it repeatable in your workflow

Treat secrets work like hygiene. The first time is annoying. After that, it should feel routine.

Start by writing down a simple secret map in plain language so anyone can update it:

- What the secret is (API key, SMTP password, webhook secret)

- Where it’s used (service, job, mobile app, vendor dashboard)

- Where it’s stored per environment (dev, staging, prod)

- Who can access it (humans, CI/CD, runtime only)

- How to rotate it (steps and what to monitor)

Next, pick one storage pattern per environment and stick to it. Consistency beats cleverness. For example: developers use a local secret store, staging uses managed secrets with limited access, and production uses the same managed secrets plus tighter audit.

Add a rotation schedule and a small incident plan that people will actually follow:

- Rotate high-risk keys on a calendar (and immediately after staff changes).

- Assume leaks happen: revoke, replace, and confirm traffic recovers.

- Log who rotated what, when, and why.

- Decide the blast radius checks (payments, email sending, webhooks).

If you build with AppMaster (appmaster.io), keep private keys in server-side configuration and deploy per environment so web and mobile builds don’t embed secrets. Then prove the process once with staging: rotate one key end to end (update store, redeploy, verify, revoke old key). After that, repeat it for the next secret.

FAQ

A secret is any value that proves identity or grants access, like API keys, database passwords, SMTP logins, and webhook signing secrets. Config is a value that can be public without harm, like timeouts, feature flag names, or a public site base URL.

If a value would cause damage when copied from a screenshot or a repo, treat it as a secret.

Use separate secrets to keep the blast radius small. If a dev laptop, test server, or staging app leaks a key, you don’t want that key to also unlock production.

Separate environments also let you use safer permissions in dev and staging, and stricter, auditable access in production.

Assume anything compiled, bundled, exported, or uploaded can be copied and inspected later. Keep secrets out of source code and out of build-time variables, and inject them at runtime through environment variables or a secret manager.

If you can swap a secret without rebuilding the app, you’re usually on the safer path.

A local .env file is fine for personal development if it never enters version control and never gets baked into images or artifacts. Put it in ignore rules, and avoid sharing it through chat, tickets, or zip files.

For staging and production, prefer protected environment settings or a secret manager so you don’t rely on files traveling around.

Don’t put private keys, SMTP passwords, database credentials, or webhook signing secrets in any client app. If the code runs on a user device or in a browser, assume attackers can extract values from it.

Instead, route sensitive actions through your backend so the secret stays server-side and the client only sends a request.

Design rotation to be a configuration change, not a code change. Store secrets outside the codebase, redeploy services to pick up new values, and keep a clear owner and reminder cadence for each key.

When possible, allow a short overlap where both old and new secrets work, then retire the old one after traffic confirms the change.

Verify every webhook request on the server using a secret that never leaves the backend. Compute the expected signature from the raw request body exactly as received and compare it safely before you parse and process the event.

Use different webhook endpoints and secrets per environment so test events can’t trigger production actions.

Avoid printing secrets, full headers, or full payloads into logs, build output, or crash reports. If you need troubleshooting, log metadata like event IDs, status codes, and masked values, not credentials.

Treat any pasted log in a ticket or chat as potentially public and redact before sharing.

Staging should mimic production behavior but remain isolated. Use separate vendor accounts or projects where you can, separate SMTP credentials, separate payment keys, and separate webhook secrets.

Add a guardrail so staging cannot read production secret stores or databases, even if someone misconfigures a deployment.

In AppMaster, keep sensitive values in environment-specific runtime settings for each deployment target, not in UI screens or client-side configuration. That helps ensure generated web and mobile builds carry only public settings, while secrets stay on the server.

A good practice is to keep the same variable names across dev, staging, and prod and only change the values per environment.