Multi-channel notification system: templates, retries, prefs

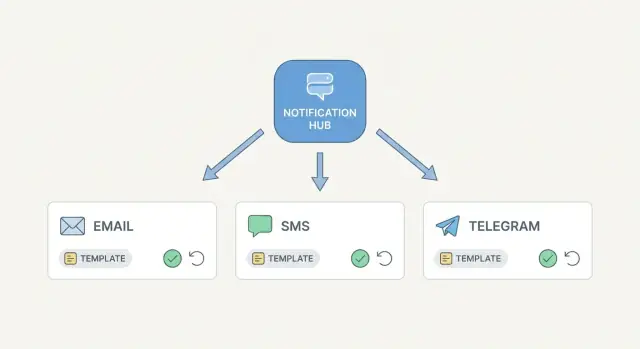

Design a multi-channel notification system for email, SMS, and Telegram with templates, delivery status, retries, and user preferences that stay consistent.

What a single notification system solves

When email, SMS, and Telegram are built as separate features, the cracks show fast. The "same" alert ends up with different wording, different timing, and different rules about who gets it. Support teams then chase three versions of the truth: one in the email provider, one in the SMS gateway, and one in a bot log.

A multi-channel notification system fixes this by treating notifications as one product, not three integrations. One event happens (password reset, invoice paid, server down), and the system decides how to deliver it across channels based on templates, user preferences, and delivery rules. The message can still be formatted differently per channel, but it stays consistent in meaning, data, and tracking.

Most teams end up needing the same foundation, regardless of which channel they started with: versioned templates with variables, delivery status tracking ("sent, delivered, failed, why"), sensible retries and fallbacks, user preferences with consent and quiet hours, and an audit trail so support can see what happened without guessing.

Success looks boring, in a good way. Messages are predictable: the right person gets the right content, at the right time, through the channels they allowed. When something goes wrong, troubleshooting is straightforward because every attempt is recorded with a clear status and a reason code.

A "new login" alert is a good example. You create it once, fill it with the same user, device, and location data, and then deliver it as an email for details, an SMS for urgency, and a Telegram message for quick confirmation. If the SMS provider times out, the system retries on schedule, logs the timeout, and can fall back to another channel instead of dropping the alert.

Core concepts and a simple data model

A multi-channel notification system stays manageable when you separate "why we are notifying" from "how we deliver it." That means a small set of shared objects, plus channel-specific details only where they truly differ.

Start with an event. An event is a named trigger like order_shipped or password_reset. Keep names consistent: lowercase, underscores, and past tense when it fits. Treat the event as the stable contract that templates and preference rules depend on.

From one event, create a notification record. This is the user-facing intent: who it is for, what happened, and what data is needed to render content (order number, delivery date, reset code). Store shared fields here such as user_id, event_name, locale, priority, and scheduled_at.

Then split into messages per channel. A notification might produce 0 to 3 messages (email, SMS, Telegram). Messages hold channel-specific fields such as destination (email address, phone, Telegram chat_id), template_id, and rendered content (subject/body for email, short text for SMS).

Finally, track each send as a delivery attempt. Attempts include provider request_id, timestamps, response codes, and a normalized status. This is what you inspect when a user says, "I never got it."

A simple model often fits in four tables or collections:

- Event (catalog of allowed event names and defaults)

- Notification (one per user intent)

- Message (one per channel)

- DeliveryAttempt (one per try)

Plan idempotency early. Give each notification a deterministic key such as (event_name, user_id, external_ref) so retries from upstream systems don’t create duplicates. If a workflow step re-runs, the idempotency key is what keeps the user from getting two SMS messages.

Store long-term only what you need to audit (event, notification, final status, timestamps). Keep short-term delivery queues and raw provider payloads only as long as you need to operate and troubleshoot.

A practical end-to-end flow (step by step)

A multi-channel notification system works best when it treats "deciding what to send" as separate from "sending it." That keeps your app fast and makes failures easier to handle.

A practical flow looks like this:

-

An event producer creates a notification request. This can be "password reset," "invoice paid," or "ticket updated." The request includes a user ID, message type, and context data (order number, amount, support agent name). Store the request immediately so you have an audit trail.

-

A router loads user and message rules. It looks up user preferences (allowed channels, opt-ins, quiet hours) and message rules (for example: security alerts must try email first). The router decides a channel plan, like Telegram, then SMS, then email.

-

The system enqueues send jobs per channel. Each job contains a template key, channel, and variables. Jobs go to a queue so the user action isn’t blocked by sending.

-

Channel workers deliver via providers. Email goes to SMTP or an email API, SMS goes to an SMS gateway, Telegram goes through your bot. Workers should be idempotent, so retrying the same job doesn’t send duplicates.

-

Status updates flow back into one place. Workers record queued, sent, failed, and when available, delivered. If a provider only confirms "accepted," record that too and treat it differently from delivered.

-

Fallbacks and retries run from the same state. If Telegram fails, the router (or a retry worker) can schedule SMS next without losing context.

Example: a user changes their password. Your backend emits one request with the user and IP address. The router sees the user prefers Telegram, but quiet hours block it at night, so it schedules email now and Telegram in the morning, while tracking both under the same notification record.

If you’re implementing this in AppMaster, keep the request, jobs, and status tables in the Data Designer and express routing and retry logic in the Business Process Editor, with sending handled asynchronously so the UI stays responsive.

Template structure that works across channels

A good template system starts with one idea: you are notifying about an event, not "sending an email" or "sending an SMS." Create one template per event (Password reset, Order shipped, Payment failed), then store channel-specific variants under that same event.

Keep the same variables across every channel variant. If email uses first_name and order_id, SMS and Telegram should use the exact same names. This prevents subtle bugs where one channel renders fine and another shows blanks.

A simple, repeatable template shape

For each event, define a small set of fields per channel:

- Email: subject, preheader (optional), HTML body, text fallback

- SMS: plain text body

- Telegram: plain text body, plus optional buttons or short metadata

The only thing that changes per channel is formatting, not the meaning.

SMS needs special rules because it’s short. Decide up front what happens when content is too long, and make it consistent: set a character limit, choose a truncation rule (cut and add ... or drop optional lines first), avoid long URLs and extra punctuation, and put the key action early (code, deadline, next step).

Locale without copying business logic

Treat language as a parameter, not a separate workflow. Store translations per event and channel, then render with the same variables. The "Order shipped" logic stays the same while subject and body change per locale.

A preview mode pays for itself. Render templates with sample data (including edge cases like a long name) so support can verify email, SMS, and Telegram variants before they go live.

Delivery status you can trust and debug

A notification is only useful if you can answer one question later: what happened to it? A good multi-channel notification system separates the message you intended to send from each attempt to deliver it.

Start with a small set of shared statuses that mean the same thing across email, SMS, and Telegram:

- queued: accepted by your system, waiting for a worker

- sending: a delivery attempt is in progress

- sent: handed off to the provider API successfully

- failed: the attempt ended with an error you can act on

- delivered: you have evidence it reached the user (when possible)

Keep these statuses on the main message record, but track every attempt in a history table. That history is what makes debugging easy: attempt #1 failed (timeout), attempt #2 succeeded, or SMS was fine while email kept bouncing.

What to store per attempt

Normalize provider responses so you can search and group issues even when providers use different words.

- provider_name and provider_message_id

- response_code (a normalized code like TIMEOUT, INVALID_NUMBER, BOUNCED)

- raw_provider_code and raw_error_text (for support cases)

- started_at, finished_at, duration_ms

- channel (email, sms, telegram) and destination (masked)

Plan for partial success. One notification may create three channel messages that share the same parent_id and business context (order_id, ticket_id, alert_type). If SMS is sent but email fails, you still want the full story in one place, not three unrelated incidents.

What "delivered" really means

"Sent" is not "delivered." For Telegram, you may only know the API accepted the message. For SMS and email, delivery often depends on webhooks or provider callbacks, and not all providers are equally reliable.

Define delivered per channel up front. Use webhook-confirmed delivery when available; otherwise treat delivered as unknown and keep reporting sent. That keeps your reporting honest and your support answers consistent.

Retries, fallbacks, and when to stop trying

Retries are where notification systems often go wrong. Retry too fast and you create storms. Retry forever and you create duplicates and support headaches. The goal is simple: try again when it has a real chance to work, and stop when it doesn’t.

Start by classifying failures. A timeout from an email provider, a 502 from an SMS gateway, or a temporary Telegram API error is usually retryable. A malformed email address, a phone number that fails validation, or a Telegram chat that blocked your bot is not. Treating these the same wastes money and floods logs.

A practical retry plan is bounded and uses backoff:

- Attempt 1: send now

- Attempt 2: after 30 seconds

- Attempt 3: after 2 minutes

- Attempt 4: after 10 minutes

- Stop after a max age (for example, 30-60 minutes for alerts)

Stopping needs a real place in your data model. Mark the message as dead-letter (or failed-permanently) once it exceeds retry limits. Keep the last error code and a short error message so support can act without guessing.

Prevent repeated sends after success with idempotency. Create an idempotency key per logical message (often notification_id + user_id + channel). If a provider responds late and you retry, the second attempt should be recognized as a duplicate and skipped.

Fallbacks should be deliberate, not automatic panic. Define escalation rules based on severity and time. Example: a password reset should not fall back to another channel (privacy risk), but a production incident alert might try SMS after two failed Telegram attempts, then email after 10 minutes.

User preferences, consent, and quiet hours

A notification system feels "smart" when it respects people. The simplest way to do that is to let users choose channels per notification type. Many teams split types into buckets like security, account, product, and marketing because the rules and legal requirements differ.

Start with a preference model that works even when a channel isn’t available. A user may have email but no phone number, or they may not have connected Telegram yet. Your multi-channel notification system should treat that as normal, not as an error.

Most systems end up needing a compact set of fields: notification type (security, marketing, billing), allowed channels per type (email, SMS, Telegram), consent per channel (date/time, source, and proof if needed), opt-out reason per channel (user choice, bounced email, "STOP" reply), and a quiet hours rule (start/end plus user time zone).

Quiet hours are where systems often break. Store the user’s time zone (not just an offset) so daylight savings changes don’t surprise anyone. When a message is scheduled during quiet hours, don’t fail it. Mark it as deferred and pick the next allowed send time.

Defaults matter, especially for critical alerts. A common approach is: security notifications ignore quiet hours (but still respect hard opt-outs where required), while non-critical updates follow quiet hours and channel choices.

Example: a password reset should go out immediately to the fastest allowed channel. A weekly digest should wait until morning and skip SMS unless the user explicitly enabled it.

Operations: monitoring, logs, and support workflows

When notifications touch email, SMS, and Telegram, support teams need answers fast: Did we send it, did it arrive, and what failed? A multi-channel notification system should feel like one place to investigate, even if it uses several providers behind the scenes.

Start with a simple admin view that anyone can use. Make it searchable by user, event type, status, and time window, and show the latest attempt first. Each row should reveal the channel, provider response, and the next planned action (retry, fallback, or stopped).

Metrics that catch problems early

Outages rarely show up as a single clean error. Track a small set of numbers and review them regularly:

- Send rate per channel (messages per minute)

- Failure rate per provider and failure code

- Retry rate (how many messages needed a second attempt)

- Time to deliver (queued to delivered, p50 and p95)

- Drop rate (stopped due to user prefs, consent, or max retries)

Correlate everything. Generate a correlation ID when the event happens (like "invoice overdue") and pass it through templating, queueing, provider calls, and status updates. In logs, that ID becomes the thread to follow when one event fans out to multiple channels.

Support-friendly replay without surprises

Replays are essential, but they need guardrails so you don’t spam people or charge twice. A safe replay flow usually means: re-send only a specific message ID (not the whole event batch), show the exact template version and rendered content before sending, require a reason and store who triggered the replay, block replay if the message was already delivered unless explicitly forced, and enforce rate limits per user and per channel.

Security and privacy basics for notifications

A multi-channel notification system touches personal data (emails, phone numbers, chat IDs) and often covers sensitive moments (logins, payments, support). Assume every message body and every log line could be seen later, then design to limit what is stored and who can see it.

Keep sensitive data out of templates whenever you can. A template should be reusable and boring: "Your code is {{code}}" is fine, but avoid embedding full account details, long tokens, or anything that could be used to take over an account. If a message must include a one-time code or reset token, store only what you need to verify it (for example, a hash and an expiry), not the raw value.

When you store or log notification events, mask aggressively. A support agent usually needs to know that a code was sent, not the code itself. The same applies to phone numbers and emails: store the full value for delivery, but show a masked version in most screens.

Minimum controls that prevent most incidents

- Role-based access: only a small set of roles can view message bodies and full recipient info.

- Separate debug access from support access so troubleshooting doesn’t become a privacy leak.

- Protect webhook endpoints: use signed callbacks or shared secrets, validate timestamps, and reject unknown sources.

- Encrypt sensitive fields at rest and use TLS in transit.

- Define retention rules: keep detailed logs briefly, then keep only aggregates or hashed identifiers.

A practical example: if a password reset SMS fails and you fall back to Telegram, store the attempt, provider status, and masked recipient, but avoid storing the reset link itself in your database or logs.

Example scenario: one alert, three channels, real outcomes

A customer, Maya, has two notification types enabled: Password reset and New login. She prefers Telegram first, then email. She only wants SMS as a fallback for password resets.

One evening, Maya requests a password reset. The system creates a single notification record with a stable ID, then expands it into channel attempts based on her current preferences.

What Maya sees is simple: a Telegram message arrives within seconds with a short reset code and an expiration time. Nothing else arrives because Telegram succeeded and no fallback was needed.

What the system records is more detailed:

- Notification: type=PASSWORD_RESET, user_id=Maya, template_version=v4

- Attempt #1: channel=TELEGRAM, status=SENT then DELIVERED

- No email or SMS attempts created (policy: stop after first success)

Later that week, a New login alert is triggered from a new device. Maya’s preferences for login alerts are Telegram only. The system sends Telegram, but the Telegram provider returns a temporary error. The system retries twice with backoff, then marks the attempt as FAILED and stops (no fallback allowed for this alert type).

Now a real failure: Maya requests another password reset while traveling. Telegram is sent, but SMS fallback is configured if Telegram does not deliver within 60 seconds. The SMS provider times out. The system records the timeout, retries once, and the second attempt succeeds. Maya gets the SMS code a minute later.

When Maya contacts support, they search by user and time window and immediately see the attempt history: timestamps, provider response codes, retry count, and the final outcome.

Quick checklist, common mistakes, and next steps

A multi-channel notification system is easier to run when you can answer two questions fast: "What exactly did we try to send?" and "What happened after that?" Use this checklist before you add more channels or events.

Quick checklist

- Clear event names and ownership (for example,

invoice.overdueowned by billing) - Template variables defined once (required vs optional, defaults, formatting rules)

- Statuses agreed up front (created, queued, sent, delivered, failed, suppressed) and what each one means

- Retry limits and backoff (max attempts, spacing, stop rule)

- Retention rules (how long you keep message bodies, provider responses, and status history)

If you do only one thing, write down the difference between sent and delivered in plain words. Sent is what your system did. Delivered is what the provider reports (and it can be delayed or missing). Mixing those two will confuse support teams and stakeholders.

Common mistakes to avoid

- Treating sent as success and reporting inflated delivery rates

- Letting channel-specific templates drift until email, SMS, and Telegram contradict each other

- Retrying without idempotency, causing duplicates when providers time out but later accept the message

- Retrying forever, turning a temporary outage into a noisy incident

- Storing too much personal data in logs and status records "just in case"

Start with one event and one primary channel, then add a second channel as a fallback (not as a parallel blast). Once the flow is stable, expand event by event, keeping templates and variables shared so messages stay consistent.

If you want to build this without hand-coding every piece, AppMaster (appmaster.io) is a practical fit for the core parts: model events, templates, and delivery attempts in the Data Designer, implement routing and retries in the Business Process Editor, and connect email, SMS, and Telegram as integrations while keeping status tracking in one place.