Integration hub design for growing SaaS stacks

Learn integration hub design to centralize credentials, track sync status, and handle errors consistently as your SaaS stack grows across many services.

Why growing SaaS stacks get messy fast

A SaaS stack often starts simple: one CRM, one billing tool, one support inbox. Then the team adds marketing automation, a data warehouse, a second support channel, and a couple of niche tools that "just need a quick sync." Before long, you have a web of point-to-point connections that nobody fully owns.

What breaks first is usually not the data. It's the glue around it.

Credentials end up scattered across personal accounts, shared spreadsheets, and random environment variables. Tokens expire, people leave, and suddenly "the integration" depends on a login nobody can find. Even when security is handled well, rotating secrets becomes painful because every connection has its own setup and its own place to update.

Visibility collapses next. Each integration reports status differently (or not at all). One tool says "connected" while silently failing to sync. Another sends vague emails that get ignored. When a sales rep asks why a customer didn't get provisioned, the answer becomes a scavenger hunt across logs, dashboards, and chat threads.

Support load rises fast because failures are hard to diagnose and easy to repeat. Small issues like rate limits, schema changes, and partial retries turn into long incidents when nobody can see the full path from "event happened" to "data arrived."

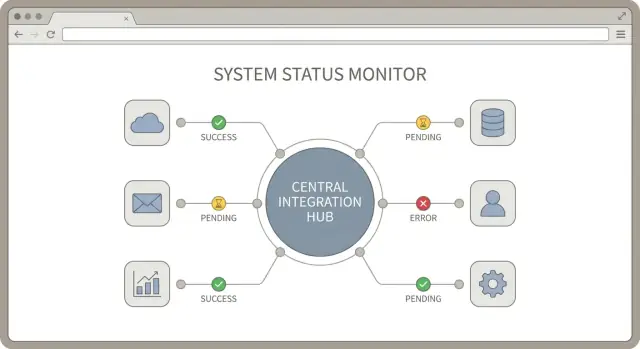

An integration hub is a simple idea: one central place where your connections to third-party services are managed, monitored, and supported. Good integration hub design creates consistent rules for how integrations authenticate, how they report sync status, and how errors are handled.

A practical hub aims for four outcomes: fewer failures (shared retry and validation patterns), faster fixes (easy tracing), safer access (central credential ownership), and lower support effort (standard alerts and messages).

If you build your stack on a platform like AppMaster, the goal is the same: keep integration operations simple enough that a non-specialist can understand what's happening, and a specialist can fix it quickly when it's not.

Map your integration inventory and data flows

Before you make big integration decisions, get a clear picture of what you already connect (or plan to connect). This is the part people skip, and it usually creates surprises later.

Start by listing every third-party service in your stack, even the "small" ones. Include who owns it (a person or team) and whether it's live, planned, or experimental.

Next, separate integrations customers can see from background automations. A user-facing integration might be "Connect your Salesforce account." An internal automation might be "When an invoice is paid in Stripe, mark the customer as active in the database." These have different reliability expectations, and they fail in different ways.

Then map the data flows by asking one question: who needs the data to do their job? Product might need usage events for onboarding. Ops needs account status and provisioning. Finance needs invoices, refunds, and tax fields. Support needs tickets, conversation history, and user identity matches. These needs shape your integration hub more than vendor APIs do.

Finally, set expectations for timing for each flow:

- Real time: user-triggered actions (connect, disconnect, instant updates)

- Near real time: a few minutes is fine (status sync, entitlement updates)

- Daily: reporting, backfills, finance exports

- On demand: support tools and admin actions

Example: "Paid invoice" may need near real time for access control, but daily for finance summaries. Capture that early and your monitoring and error handling become much easier to standardize.

Decide what your integration hub should do

Good integration hub design starts with boundaries. If the hub tries to do everything, it becomes the bottleneck for every team. If it does too little, you end up with a dozen one-off scripts that all behave differently.

Write down what the hub owns and what it doesn't. A practical split is:

- The hub owns connection setup, credential storage, scheduling, and a consistent contract for status and errors.

- Downstream services own business decisions, like which customers should be invoiced or what counts as a qualified lead.

Pick one entry point for all integrations and stick to it. That entry point can be an API (other systems call the hub) or a job runner (the hub runs scheduled pulls and pushes). Using both is fine, but only if they share the same internal pipeline so retries, logging, and alerts behave the same way.

A few decisions keep the hub focused: standardize how integrations are triggered (webhook, schedule, manual rerun), agree on a boundary payload shape (even if partners differ), decide what you persist (raw events, normalized records, both, or neither), define what "done" means (accepted, delivered, confirmed), and assign ownership for partner-specific quirks.

Decide where transformations happen. If you normalize data in the hub, downstream services stay simpler, but the hub needs stronger versioning and tests. If you keep the hub thin and pass raw partner payloads through, each downstream service must learn each partner format. Many teams land in the middle: normalize only shared fields (IDs, timestamps, basic status) and keep domain rules downstream.

Plan for multi-tenant from day one. Decide whether the unit of isolation is a customer, workspace, or org. That choice affects rate limits, credential storage, and backfills. When one customer's Salesforce token expires, you should pause only that tenant's jobs, not the whole pipeline. Tools like AppMaster can help model tenants and workflows visually, but the boundaries still need to be explicit before you build.

Centralize credentials without creating a security risk

A credential vault can either make your life calm or turn into a permanent incident risk. The goal is simple: one place to store access, without giving every system and teammate more power than they need.

OAuth and API keys show up in different places. OAuth is common for user-facing apps like Google, Slack, Microsoft, and many CRMs. A user approves access, and you store an access token plus a refresh token. API keys are more common for server-to-server tools and older APIs. They can be long-lived, which makes safe storage and rotation even more important.

Store everything encrypted and scope it to the right tenant. In a multi-customer product, treat credentials as customer data. Keep strict isolation so a token for Tenant A can never be used for Tenant B, even by mistake. Also store the metadata you'll need later, like which connection it belongs to, when it expires, and what permissions were granted.

Practical rules that prevent most problems:

- Use least-privilege scopes. Ask only for the permissions your sync needs today.

- Keep credentials out of logs, error messages, and support screenshots.

- Rotate keys when possible, and track which systems still use the old key.

- Separate environments. Never reuse production credentials in staging.

- Limit who can view or re-authorize a connection in your admin UI.

Plan for refresh and revocation without breaking sync. For OAuth, refresh should happen automatically in the background, and your hub should handle "token expired" by refreshing once and retrying safely. For revocation (a user disconnects, a security team disables an app, or scopes change), stop the sync, mark the connection as needs_auth, and keep a clear audit trail of what happened.

If you build your hub in AppMaster, treat credentials as a protected data model, keep access in backend-only logic, and expose only connected/disconnected status to the UI. Operators can fix a connection without ever seeing the secret.

Make sync status visible and consistent

When you connect many tools, "is it working?" becomes a daily question. The fix isn't more logs. It's a small, consistent set of sync signals that look the same for every integration. Good integration hub design treats status as a first-class feature.

Start by defining a short list of connection states and using them everywhere: in the admin UI, in alerts, and in support notes. Keep the names plain so a non-technical teammate can act on them.

- connected: credentials are valid and sync is running

- needs_auth: the user must re-authorize (expired token, revoked access)

- paused: intentionally stopped (maintenance, customer request)

- failing: repeated errors and human attention is needed

Track three timestamps per connection: last sync start, last sync success, and last error time. They tell a quick story without digging.

A small per-integration view helps support teams move fast. Each connection page should show the current state, those timestamps, and the last error message in a clean, user-facing format (no stack traces). Add a short recommended action line like "Re-auth required" or "Rate limit, retrying."

Add a few health signals that predict trouble before users notice it: backlog size, retry count, rate limit hits, and last successful throughput (roughly how many items synced last run).

Example: your CRM sync is connected, but backlog is rising and rate limit hits spike. That's not an outage yet, but it's a clear sign to reduce sync frequency or batch requests. If you're building your hub in AppMaster, these status fields map neatly into a Data Designer model and a simple support dashboard UI your team can use daily.

Design the data sync flow step by step

A reliable sync is more about repeatable steps than fancy logic. Start with one clear execution model, then add complexity only where you need it.

1) Choose how work enters the hub

Most teams use a mix, but each connector should have a primary trigger so it's easy to reason about:

- Events (webhooks) for near real time changes

- Jobs for actions you must run to completion (like "create invoice, then mark paid")

- Scheduled pulls for systems that can't push, or for safety backfills

If you're building in AppMaster, this often maps to a webhook endpoint, a background process, and a scheduled task, all feeding the same internal pipeline.

2) Normalize first, then process

Different vendors name the same thing in different ways (customerId vs contact_id, status strings, date formats). Convert every incoming payload into one internal format before you apply business rules. It keeps the rest of your hub simpler and makes connector changes less painful.

3) Make every write idempotent

Retries are normal. Your hub should be able to run the same action twice without creating duplicates. A common approach is to store an external ID and a "last processed version" (timestamp, sequence number, or event ID). If you see the same item again, you skip or update safely.

4) Queue work and put a ceiling on waiting

Third-party APIs can be slow or hang. Put normalized tasks onto a durable queue, then process them with explicit timeouts. If a call takes too long, fail it, record why, and retry later instead of blocking everything else.

5) Respect rate limits on purpose

Handle limits with both backoff and per-connector throttling. Back off on 429/5xx responses with a capped retry schedule, set separate concurrency limits per connector (CRM is not billing), and add jitter to avoid retry bursts.

Example: a "new paid invoice" arrives from billing via webhook, gets normalized and queued, then creates or updates the matching account in your CRM. If the CRM rate limits you, that connector slows down without delaying support ticket syncs.

Error handling your team can actually support

A hub that "sometimes fails" is worse than no hub. The fix is a shared way to describe errors, decide what happens next, and tell non-technical admins what to do.

Start with a standard error shape that every connector returns, even if third-party payloads differ. That keeps your UI, alerts, and support playbooks consistent.

- code: stable identifier (for example,

RATE_LIMIT) - message: short, readable summary

- retryable: true/false

- context: safe metadata (integration name, endpoint, record ID)

- provider_details: sanitized snippet for troubleshooting

Then classify failures into a few buckets (keep it small): auth, validation, timeout, rate limit, and outage.

Attach clear retry rules to each bucket. Rate limits get delayed retries with backoff. Timeouts can retry quickly a small number of times. Validation is manual until data is fixed. Auth pauses the integration and asks an admin to reconnect.

Keep raw third-party responses, but store them safely. Redact secrets (tokens, API keys, full card data) before saving. If it can grant access, it doesn't belong in logs.

Write two messages per error: one for admins and one for engineers. An admin message might be: "Salesforce connection expired. Reconnect to resume syncing." The engineer view can include the sanitized response, request ID, and the step that failed. This is where a consistent hub pays off, whether you implement flows in code or with a visual tool like AppMaster's Business Process Editor.

Common traps and how to avoid them

Many integration projects fail for boring reasons. The hub works in a demo, then falls apart when you add more tenants, more data types, and more edge cases.

One big trap is mixing connection logic with business logic. When "how to talk to the API" sits in the same code path as "what a customer record means," every new rule risks breaking the connector. Keep adapters focused on auth, paging, rate limits, and mapping. Keep business rules in a separate layer that you can test without hitting third-party APIs.

Another common issue is treating tenant state as global. In a B2B product, each tenant needs its own tokens, cursors, and sync checkpoints. If you store "last sync time" in one shared place, one customer can overwrite another and you get missing updates or cross-tenant data leaks.

Five traps that show up again and again, plus the simple fix:

- Connection logic and business logic are tangled. Fix: create a clear adapter boundary (connect, fetch, push, transform), then run business rules after the adapter.

- Tokens are stored once and reused across tenants. Fix: store credentials and refresh tokens per tenant, and rotate them safely.

- Retries run forever. Fix: use capped retries with backoff, and stop after a clear limit.

- Every error is treated as retryable. Fix: classify errors and surface auth problems immediately.

- No audit trail exists. Fix: write audit logs for who synced what, when, and why it failed, including request IDs and external object IDs.

Retries deserve special care. If a create call times out, retrying can create duplicates unless you use idempotency keys or a strong upsert strategy. If the third-party API doesn't support idempotency, track a local write ledger so you can detect and avoid repeated writes.

Don't skip audit logs. When support asks why a record is missing, you need an answer in minutes, not a guess. Even if you build your hub with a visual tool like AppMaster, make logs and per-tenant state first-class.

Quick checklist for a reliable integration hub

A good integration hub is boring in the best way: it connects, reports its health clearly, and fails in ways your team can understand.

Security and connection basics

Start by checking how each integration authenticates and what you do with those credentials. Ask for the smallest set of permissions that still lets the job run (read-only where possible). Store secrets in a dedicated secret store or encrypted vault and rotate them without code changes. Make sure logs and error messages never include tokens, API keys, refresh tokens, or raw headers.

Once credentials are safe, confirm that every customer connection has a single, clear source of truth.

Visibility, retries, and support readiness

Operational clarity is what keeps integrations manageable when you have dozens of customers and many third-party services.

Track connection state per customer (connected, needs_auth, paused, failing) and expose it in the admin UI. Record a last successful sync timestamp per object or per sync job, not just "we ran something yesterday." Make the last error easy to find with context: which customer, which integration, which step, which external request, and what happened next.

Keep retries bounded (max attempts and a cutoff window), and design writes to be idempotent so reruns don't create duplicates. Set a support goal: someone on the team should be able to locate the latest failure and its details in under two minutes without reading code.

If you're building the hub UI and status tracking quickly, a platform like AppMaster can help you ship an internal dashboard and workflow logic fast while still generating production-ready code.

A realistic example: three integrations, one hub

Picture a SaaS product that needs three common integrations: Stripe for billing events, HubSpot for sales handoffs, and Zendesk for support tickets. Instead of wiring each tool directly to your app, route them through one integration hub.

Onboarding starts in the admin panel. An admin clicks "Connect Stripe", "Connect HubSpot", and "Connect Zendesk". Each connector stores credentials in the hub, not in random scripts or employee laptops. Then the hub runs an initial import:

- Stripe: customers, subscriptions, invoices (plus webhook setup for new events)

- HubSpot: companies, contacts, deals

- Zendesk: organizations, users, recent tickets

After import, the first sync kicks off. The hub writes a sync record for each connector so everyone sees the same story. A simple admin view answers most questions: connection state, last successful sync time, current job (importing, syncing, idle), error summary and code, and next scheduled run.

Now it's a busy hour and Stripe rate limits your API calls. Instead of failing the whole system, the Stripe connector marks the job as retrying, stores partial progress (for example, "invoices up to 10:40"), and backs off. HubSpot and Zendesk keep syncing.

Support gets a ticket: "Billing looks stale." They open the hub and see Stripe in failing with a rate limit error. Resolution is procedural:

- Re-auth Stripe only if the token is actually invalid

- Replay the last failed job from the saved checkpoint

- Confirm success by checking last sync time and a small spot-check (one invoice, one subscription)

If you build on a platform like AppMaster, this flow maps cleanly to visual logic (job states, retries, admin screens) while still generating real backend code for production.

Next steps: build iteratively and keep operations simple

Good integration hub design is less about building everything at once and more about making each new connection predictable. Start with a small set of shared rules every connector must follow, even if the first version feels "too simple."

Begin with consistency: standard states for sync jobs (pending, running, succeeded, failed), a short set of error categories (auth, rate limit, validation, upstream outage, unknown), and audit logs that answer who ran what, when, and with which records. If you can't trust status and logs, dashboards and alerts will just create noise.

Add connectors one at a time using the same templates and conventions. Each connector should reuse the same credential flow, the same retry rules, and the same way of writing status updates. That repetition is what keeps the hub supportable when you have ten integrations instead of three.

A practical rollout plan:

- Pick 1 pilot tenant with real usage and clear success criteria

- Build 1 connector end to end, including status and logs

- Run it for a week, fix the top 3 failure modes, then document the rules

- Add the next connector using the same rules, not custom fixes

- Expand to more tenants gradually, with a simple rollback plan

Introduce dashboards and alerts only after the underlying status data is correct. Start with one screen that shows last sync time, last result, next run, and the latest error message with category.

If you prefer a no-code approach, you can model the data, build sync logic, and expose status screens in AppMaster, then deploy to your cloud or export source code. Keep the first version boring and observable, then improve performance and edge cases once operations are stable.

FAQ

Start with a simple inventory: every third-party tool, who owns it, and whether it’s live or planned. Then write down the data that moves between systems and why it matters to a team (support, finance, ops). That map will tell you what needs real time behavior, what can run daily, and what needs the strongest monitoring.

Own the shared plumbing: connection setup, credential storage, scheduling/triggers, consistent status reporting, and consistent error handling. Keep business decisions outside the hub, so you don’t have to change connector code every time product rules change. This boundary keeps the hub useful without becoming a bottleneck.

Use one primary entry point per connector so it’s easy to reason about failures. Webhooks are best when you need near real time updates, scheduled pulls work when providers can’t push events, and job-style workflows are good when you must run steps in order. Whatever you choose, keep retries, logging, and status updates the same across all triggers.

Treat credentials as customer data and store them encrypted with strict tenant isolation. Don’t expose tokens in logs, UI screens, or support screenshots, and don’t reuse production secrets in staging. Also store the metadata you’ll need to operate safely, like expiration time, scopes, and which tenant and connection a token belongs to.

OAuth is best when customers need to connect their own accounts and you want revocable access with scoped permissions. API keys can be simpler for server-to-server integrations but are often long-lived, so rotation and access control matter more. If you can choose, prefer OAuth for user-facing connections and keep keys tightly limited and regularly rotated.

Keep tenant state separate for everything: tokens, cursors, checkpoints, retry counters, and backfill progress. A failure for one tenant should pause only that tenant’s jobs, not the entire connector. This isolation prevents cross-tenant data leaks and makes support issues easier to contain.

Use a small set of plain states across every connector, such as connected, needs_auth, paused, and failing. Record three timestamps per connection: last sync start, last sync success, and last error time. With those signals, most “is it working?” questions can be answered without reading logs.

Make every write idempotent so retries don’t create duplicates. Typically that means storing an external object ID plus a “last processed” marker, and performing upserts instead of blind creates. If the provider doesn’t support safe idempotency, keep a local write ledger so you can detect repeated attempts before you write again.

Handle rate limits deliberately: throttle per connector, back off on 429 and transient errors, and add jitter so retries don’t pile up at the same time. Keep work in a durable queue with timeouts so slow API calls don’t block other integrations. The goal is to slow down one connector without stalling the whole hub.

If you want a no-code approach, model connections, tenants, and status fields in AppMaster’s Data Designer, then implement sync workflows in the Business Process Editor. Keep credentials in backend-only logic and expose only safe status and action prompts in the UI. You can ship an internal operations dashboard quickly and still deploy as production-ready generated code.