Incident management app for IT teams: workflows to postmortems

Plan and build an incident management app for IT teams with severity workflows, clear ownership, timelines, and postmortems in one internal tool.

What problem an internal incident app actually solves

When an outage hits, most teams grab whatever is open: a chat thread, an email chain, maybe a spreadsheet someone updates when they have a minute. Under pressure, that setup breaks in the same ways every time: ownership gets fuzzy, timestamps go missing, and decisions disappear into the scroll.

A simple incident management app fixes the basics. It gives you one place where the incident lives, with a clear owner, a severity level everyone agrees on, and a timeline of what happened and when. That single record matters because the same questions come up in every incident: Who is leading? When did it start? What’s the current status? What’s already been tried?

Without that shared record, handoffs waste time. Support tells customers one thing while engineering is doing another. Managers ask for updates that pull responders away from the fix. Afterward, nobody can rebuild the timeline with confidence, so the postmortem turns into guesswork.

The goal isn’t to replace your monitoring, chat, or ticketing. Alerts can still start elsewhere. The point is to capture the decision trail and keep humans aligned.

IT operations and on-call engineers use it to coordinate response. Support uses it to give accurate updates quickly. Managers use it to see progress without interrupting responders.

Example scenario: a P1 outage from alert to closure

At 9:12 AM, monitoring flags a spike in 500 errors on the customer portal. A support agent also reports, “Login fails for most users.” The on-call IT lead opens a P1 incident in the incident app and attaches the first alert plus a screenshot from support.

With a P1, behavior changes fast. The incident owner pulls in the backend owner, the database owner, and a support liaison. Non-essential work pauses. Planned deployments stop. The team agrees on an update cadence (for example, every 15 minutes). A shared call starts, but the incident record remains the source of truth.

By 9:18 AM, someone asks, “What changed?” The timeline shows a deploy at 8:57 AM, but it doesn’t say what was deployed. The backend owner rolls back anyway. Errors drop, then return. Now the team suspects the database.

Most delays show up in a few predictable places: unclear handoffs (“I thought you were checking that”), missing context (recent changes, known risks, current owner), and scattered updates across chat, tickets, and email.

At 9:41 AM, the database owner finds a runaway query started by a scheduled job. They disable the job, restart the affected service, and confirm recovery. Severity is downgraded to P2 for monitoring.

Good closure isn’t “it works again.” It’s a clean record: a minute-by-minute timeline, the final root cause, who made which decision, what was paused, and follow-up work with owners and due dates. That’s how a stressful P1 turns into learning instead of repeat pain.

Data model: the simplest structure that still works

A good incident tool is mostly a good data model. If records are vague, people will argue about what the incident is, when it started, and what’s still open.

Keep the core entities close to how IT teams already talk:

- Incident: the container for what happened

- Service: what the business runs (API, database, VPN, billing)

- User: responders and stakeholders

- Update: short status notes over time

- Task: concrete work during the incident (and after)

- Postmortem: one write-up tied to the incident, with action items

To prevent confusion later, give the Incident a few structured fields that are always filled in. Free text helps, but it shouldn’t be the only source of truth. A practical minimum is: a clear title, impact (what users experience), affected services, start time, current status, and severity.

Relationships matter more than extra fields. One incident should have many updates and many tasks, plus a many-to-many link to services (because outages often hit multiple systems). A postmortem should be one-to-one with an incident, so there’s a single final story.

Example: a “Checkout errors” incident links to Services “Payments API” and “PostgreSQL,” has updates every 15 minutes, and tasks like “Roll back deploy” and “Add retry guard.” Later, the postmortem captures root cause and creates longer-term tasks.

Severity levels and response targets

When people are stressed, they need simple labels that mean the same thing to everyone. Define P1 to P4 in plain language and show the definition right next to the severity field.

- P1 (Critical): Core service is down or data loss is likely. Many users blocked.

- P2 (High): Major feature is broken, but there’s a workaround or limited blast radius.

- P3 (Medium): Non-urgent issue, small group affected, minimal business impact.

- P4 (Low): Cosmetic or minor bug, schedule for later.

Response targets should read like commitments. A simple baseline (adjust to your reality):

| Severity | First response (ack) | First update | Update frequency |

|---|---|---|---|

| P1 | 5 min | 15 min | every 30 min |

| P2 | 15 min | 30 min | every 60 min |

| P3 | 4 hours | 1 business day | daily |

| P4 | 2 business days | 1 week | weekly |

Keep escalation rules mechanical. If a P2 misses its update cadence or impact grows, the system should prompt a severity review. To avoid thrash, limit who can change severity (often the incident owner or incident commander), while still letting anyone request a review in a comment.

A quick impact matrix also helps teams pick severity fast. Capture it as a few required fields: users affected, revenue risk, safety, compliance/security, and whether a workaround exists.

Workflow states that guide people during stress

During an incident, people don’t need more options. They need a small set of states that make the next step obvious.

Start with the steps you already follow on a good day, then keep the list short. If you have more than 6 or 7 states, teams will argue about wording instead of fixing the issue.

A practical set:

- New: alert received, not yet confirmed

- Acknowledged: someone owns it, first response started

- Investigating: confirm impact, narrow likely cause

- Mitigating: actions in progress to reduce impact

- Monitoring: service looks stable, watching for relapse

- Resolved: service restored, ready for review

Each status needs clear entry and exit rules. For example:

- You can’t move to Acknowledged until an owner is set and the next action is written in one sentence.

- You can’t move to Mitigating until at least one concrete mitigation task exists (rollback, feature flag off, capacity added).

Use transitions to enforce the fields people forget. A common rule: you can’t close an incident without a short root cause summary and at least one follow-up item. If “RCA: TBD” is allowed, it tends to stay that way.

The incident page should answer three questions at a glance: who owns this, what the next action is, and when the last update was posted.

Assignment and escalation rules

When an incident is noisy, the fastest way to lose time is vague ownership. Your app should make one person clearly responsible, while still making it easy for others to help.

A simple pattern that holds up:

- Primary owner: drives the response, posts updates, decides next steps

- Helpers: take tasks (diagnostics, rollback, comms) and report back

- Approver: a lead who can approve risky actions

Assignment should be explicit and auditable. Track who set the owner, who accepted it, and every change after that. “Accepted” matters, because assigning someone who’s asleep or offline isn’t real ownership.

On-call vs team-based assignment usually depends on severity. For P1/P2, default to on-call rotation so there’s always a named owner. For lower severities, team-based assignment can work, but still require a single primary owner within a short window.

Plan for vacations and outages in your human process, not just your systems. If the assigned person is marked unavailable, route to a secondary on-call or team lead. Keep it automatic, but visible so it can be corrected quickly.

Escalation should trigger on both severity and silence. A useful starting point:

- P1: escalate if no owner acceptance in 5 minutes

- P1/P2: escalate if no update in 15 to 30 minutes

- Any severity: escalate if the state stays “Investigating” beyond the response target

Timelines, updates, and notifications

A good timeline is shared memory. During an incident, context disappears fast. If you capture the right moments in one place, handoffs get easier and the postmortem is mostly written before anyone opens a document.

What the timeline should capture

Keep the timeline opinionated. Don’t turn it into a chat log. Most teams rely on a small set of entries: detection, acknowledgement, key mitigation steps, restore, and closure.

Each entry needs a timestamp, an author, and a short plain description. Someone joining late should be able to read five entries and understand what’s going on.

Update types that keep things clear

Different updates serve different audiences. It helps when entries have a type, such as internal note (raw details), customer-facing update (safe wording), decision (why you chose option A), and handoff (what the next person must know).

Reminders should follow severity, not personal preference. If the timer hits, ping the current owner first, then escalate if it’s missed repeatedly.

Notifications should be targeted and predictable. A small rule set is usually enough: notify on creation, severity change, restore, and overdue updates. Avoid notifying the whole company for every change.

Postmortems that lead to real follow-up work

A postmortem should do two jobs: explain what happened in plain language, and make the same failure less likely next time.

Keep the write-up short, and force the output into actions. A practical structure includes: summary, customer impact, root cause, fixes applied, and follow-ups.

Follow-ups are the point. Don’t leave them as a paragraph at the end. Turn each follow-up into a tracked task with an owner and a due date, even if the due date is “next sprint.” That’s the difference between “we should improve monitoring” and “Alex adds a DB connection saturation alert by Friday.”

Tags make postmortems useful later. Add 1 to 3 themes to every incident (monitoring gap, deployment, capacity, process). After a month, you can answer basic questions like whether most P1s come from releases or missing alerts.

Evidence should be easy to attach, not mandatory. Support optional fields for screenshots, log snippets, and references to external systems (ticket IDs, chat threads, vendor case numbers). Keep it lightweight so people will actually fill it out.

Step-by-step: building the mini-system as one internal app

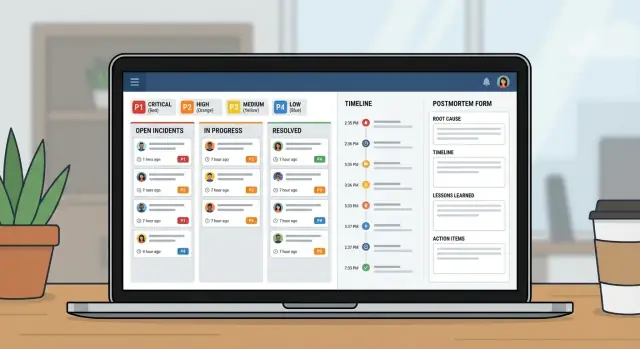

Treat this like a small product, not a spreadsheet with extra columns. A good incident app is really three views: what’s happening now, what to do next, and what to learn afterward.

Start by sketching the screens people will open under pressure:

- Queue: open incidents with a couple of filters (Open, Needs update, Waiting on vendor, Closed)

- Incident page: severity, owner, current status, timeline, tasks, and the latest update

- Postmortem page: impact, root cause, action items, owners

Build the data model and permissions together. If everyone can edit everything, history gets messy. A common approach is: broad view access for IT, controlled state/severity changes, responders can add updates, and a clear owner for postmortem approval.

Then add workflow rules that prevent half-filled incidents. Required fields should depend on state. You might allow “New” with just title and reporter, but require “Mitigating” to include an impact summary, and require “Resolved” to include a root cause summary plus at least one follow-up task.

Finally, test by replaying 2 to 3 past incidents. Have one person act as incident commander and one as a responder. You’ll quickly see which statuses are unclear, which fields people skip, and where you need better defaults.

Common mistakes and how to avoid them

Most incident systems fail for simple reasons: people can’t remember the rules when they’re stressed, and the app doesn’t capture the facts you need later.

Mistake 1: Too many severities or statuses

If you have six severity levels and ten states, people will guess. Keep severities to 3 to 4 and keep states focused on what someone should do next.

Mistake 2: No single owner

When everyone is “watching it,” nobody is driving it. Require one named owner before the incident can move forward, and make handoffs explicit.

Mistake 3: Timelines you can’t trust

If “what happened when” relies on chat history, postmortems become arguments. Auto-capture opened, acknowledged, mitigated, and resolved timestamps, and keep timeline entries short.

Also avoid closing with vague root cause notes like “network issue.” Require one clear root cause statement plus at least one concrete next step.

Launch checklist and next steps

Before you roll this out to the whole IT org, stress test the basics. If people can’t find the right button in the first two minutes, they’ll fall back to chat threads and spreadsheets.

Focus on a short set of launch checks: roles and permissions, clear severity definitions, enforced ownership, reminder rules, and an escalation path when response targets are missed.

Pilot with one team and a few services that generate frequent alerts. Run it for two weeks, then adjust based on real incidents.

If you want to build this as a single internal tool without stitching together spreadsheets and separate apps, AppMaster (appmaster.io) is one option. It lets you create a data model, workflow rules, and web/mobile interfaces in one place, which fits well with an incident queue, incident page, and postmortem tracking.

FAQ

It replaces scattered updates with one shared record that answers the basics fast: who owns the incident, what users are seeing, what’s been tried, and what happens next. That reduces time lost to handoffs, conflicting messages, and “can you summarize?” interruptions.

Start the incident as soon as you believe there’s real customer or business impact, even if the root cause is unclear. You can open it with a draft title and “impact unknown,” then tighten the details as you confirm severity and scope.

Keep it small and structured: a clear title, impact summary, affected service(s), start time, current status, severity, and a single owner. Add updates and tasks as the situation evolves, but don’t rely on free text for the core facts.

Use 3 to 4 levels with plain meanings that don’t require debate. A good default is P1 for core outage or data-loss risk, P2 for major feature impact with some workaround or limited scope, P3 for smaller-impact issues, and P4 for minor or cosmetic problems.

Make the targets feel like commitments, not guesses: time to acknowledge, time to first update, and an update cadence. Then trigger reminders and escalation when the cadence is missed, because “silence” is often the real failure during incidents.

Aim for about six: New, Acknowledged, Investigating, Mitigating, Monitoring, and Resolved. Each state should make the next step obvious, and transitions should enforce what people forget under stress, like requiring an owner before Acknowledged or requiring a root cause summary before closure.

Require one primary owner who is accountable for driving the response and posting updates. Track acceptance explicitly so you don’t “assign” someone who’s offline, and make handoffs a recorded event so the next person doesn’t restart the investigation from scratch.

Capture only the moments that matter: detection, acknowledgement, key decisions, mitigation steps, restore, and closure, each with a timestamp and author. Treat it as shared memory, not a chat transcript, so someone joining late can catch up in minutes.

Keep it short and action-focused: what happened, customer impact, root cause, what you changed during mitigation, and follow-up items with owners and due dates. The write-up is useful, but the tracked tasks are what stop the same incident from repeating.

Yes, if you model incidents, updates, tasks, services, and postmortems as real data and enforce workflow rules in the app. With AppMaster, teams can build that data model plus web/mobile screens and state-based validations in one place, so the process doesn’t fall back to spreadsheets under pressure.