File uploads at scale: validation, storage, and access

File uploads at scale need clear validation, tidy storage paths, expiring download links, and strong permissions to protect user files.

What makes user file uploads hard at scale

User uploads feel simple with a handful of test users. They get hard when real people start sending real files: large photos, scanned PDFs, and mystery documents with the wrong extension. At that point, file uploads at scale stop being a button on a form and turn into a safety and operations problem.

The first cracks usually show up in three places: security, cost, and privacy. Attackers try to upload malware, users upload files your app can’t open, and teams accidentally expose sensitive documents through a public URL. Storage bills grow, and bandwidth grows too when the same file gets downloaded again and again.

Images and PDFs create different problems. Images can be huge, come in many formats, and often include hidden metadata (like location). You also need thumbnails and resizing to keep the app fast. PDFs are tricky to preview safely, can include embedded content, and often contain sensitive records (invoices, IDs, contracts) that shouldn’t be broadly accessible.

At scale, you’re usually dealing with more users uploading at the same time, bigger files and more total storage, more downloads and retries from unstable networks, and more rules: different teams, roles, and retention needs.

The goal isn’t uploads that work. The goal is safe uploads that stay easy to manage months later: clear rules, predictable storage paths, audit-friendly metadata, and access controls that match how your business actually shares files.

Map your file types and who should access them

Before you tune storage or security, get clear on what people will upload and who is allowed to see it. Most upload problems at scale aren’t really storage issues. They’re mismatched expectations about access, retention, and risk.

Start by listing real file categories, not just documents and images. An avatar behaves very differently from a contract PDF, and a support screenshot is different from a monthly report.

One practical way to map uploads is to tie each category to an access pattern:

- Avatars and public profile images are often readable by many people, and editable only by the owner.

- Receipts and invoices are private by default, shared only with finance roles or the account owner.

- Contracts and compliance files are highly restricted and often need audit trails and stricter retention rules.

- Reports and exports can be shared within a team but should be scoped to the right workspace or customer.

- Ticket attachments are usually private to the ticket participants and sometimes time-limited.

Then take a quick risk snapshot. Uploads can hide malware, leak sensitive data (IDs, bank info, medical details), or expose broken permissions where guessing a URL grants access. That’s why file uploads at scale are as much about file access control as they are about bytes.

Performance matters too. Large PDFs, high-resolution images, and flaky mobile networks cause partial uploads and retries. Decide up front which uploads must succeed reliably (invoices, IDs) and which are optional (a profile banner).

For each file type, answer a few questions early so you don’t have to rewrite later:

- Who can upload, view, replace, and delete it?

- Is it private, shared within a group, or public?

- Should access expire or be revocable instantly?

- What happens if the upload is interrupted and retried?

- How long do you keep it, and who can export it?

If you build with a tool like AppMaster, treat these answers as product rules first, then implement them in your data model and endpoints so permissions stay consistent across web and mobile.

File upload validation rules that prevent problems early

If you want file uploads at scale to stay safe and predictable, validation is your first line of defense. Good rules stop bad files before they hit storage, and they reduce support tickets because users get clear feedback.

Start with an allowlist, not a blocklist. Check the filename extension and also verify the MIME type from the uploaded content. Relying on extension alone is easy to bypass. Relying on MIME alone can be inconsistent across devices.

Size limits should match the file type and your product rules. Images might be fine at 5 to 10 MB, while PDFs may need a higher cap. Videos are a different problem entirely and usually need their own pipeline. If you have paid tiers, tie limits to the plan so you can say, “Your plan allows up to 10 MB PDFs,” instead of showing a vague error.

Some files need deeper checks. For images, validate width and height (and sometimes aspect ratio) to avoid giant uploads that slow down pages. For PDFs, page count can matter when your use case expects a small range.

Rename files on upload. User filenames often include spaces, emojis, or repeated names like scan.pdf. Use a generated ID plus a safe extension, and store the original name in metadata for display.

A validation baseline that works for many apps looks like this:

- Allowlist types (extension + MIME), reject everything else.

- Set max size per type (and optionally per plan).

- Validate image dimensions and reject extreme sizes.

- Validate PDF page count when your use case expects it.

- Rename to a safe, unique filename and keep the original as metadata.

When validation fails, show one clear message the user can act on, like “PDFs must be under 20 MB and 50 pages.” At the same time, log the technical details for admins (detected MIME, size, user ID, and reason). In AppMaster, these checks can live in your Business Process so every upload path follows the same rules.

Data model for uploads and file metadata

A good data model makes uploads boring. The goal is to track who owns a file, what it’s for, and whether it’s safe to use, without tying your app to one storage vendor.

A reliable pattern is a two-step flow. First, create an upload record in your database and return an upload ID. Second, upload the binary to storage using that ID. This avoids mystery files sitting in a bucket with no matching row, and it lets you enforce permissions before any bytes move.

A simple uploads table (or collection) is usually enough. In AppMaster, this maps cleanly to a PostgreSQL model in the Data Designer and can be used across web and mobile apps.

Store what you’ll actually need later for support and audits:

- Owner reference (

user_id) and scope (org_idorteam_id) - Purpose (avatar, invoice_pdf, ticket_attachment)

- Original filename, detected MIME type, and

size_bytes - Storage pointer (bucket/container,

object_key) plus checksum (optional) - Timestamps (

created_at,uploaded_at) and the uploader’s IP/device (optional)

Keep the state model small so it stays readable. Four states cover most products:

pending: record exists, upload not completeduploaded: bytes storedverified: passed checks and ready to useblocked: failed checks or policy

Plan cleanup from day one. Abandoned pending uploads happen when users close a tab or lose connection. A daily job can delete storage objects for expired pending rows, mark rows as canceled for reporting, remove old blocked items after a retention window, and keep verified files until business rules say otherwise.

This model gives you traceability and control without adding complexity.

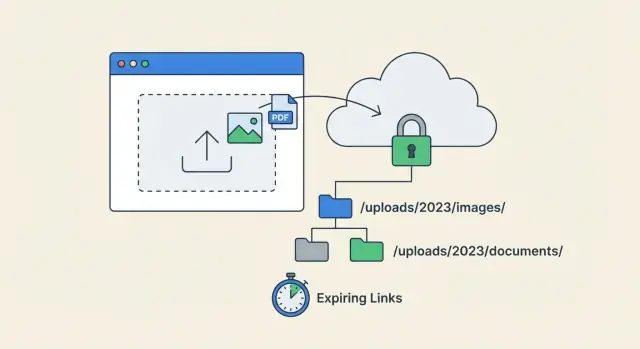

Storage organization that stays tidy over time

When file uploads at scale start piling up, the biggest risk isn’t storage cost. It’s mess. If your team can’t tell what a file is, who it belongs to, and whether it’s still current, you’ll ship bugs and leak data.

Pick one predictable folder strategy and stick to it. Many teams organize by tenant (company), then by purpose, then by date. Others do tenant, user, purpose. The exact choice matters less than consistency. Dates help keep directories from growing without bound and make cleanup jobs simpler.

Avoid putting personal data in paths or filenames. Don’t embed email addresses, full names, invoice numbers, or phone numbers. Use random IDs instead. If you need to search by human meaning, store that in database metadata, not in the object key.

Keep originals and derivatives separate so rules stay clear. Store the original upload once, and store thumbnails or previews under a different prefix. That makes it easier to apply different retention policies and permissions (a preview might be allowed in more places than the original).

A simple, durable naming approach:

- Partition by tenant ID (or workspace ID)

- Add a purpose prefix (avatars, invoices, attachments)

- Add a time bucket (YYYY/MM)

- Use an opaque file ID as the filename

- Store derivatives under a separate prefix (previews, thumbnails)

Decide how you’ll handle versions. If users can replace files, either overwrite the same object key (simple, no history) or create a new version and mark the old one as inactive (more audit-friendly). Many teams keep history for compliance documents and overwrite for profile pictures.

Write your naming rules down. In AppMaster, treat it like any shared convention: keep it in your project docs so backend logic, UI builders, and future integrations all generate the same paths.

Permissions and access control patterns

With file uploads at scale, permissions are where small shortcuts turn into big incidents. Start with deny-by-default: every uploaded file is private until a rule explicitly allows access.

It helps to separate two questions: who can see the record, and who can fetch the bytes. Those aren’t the same. Many apps should let someone view metadata (file name, size, uploaded date) without being able to download the file.

Common access patterns

Pick one primary pattern per file type, then add exceptions carefully:

- Owner-only: only the uploader (and service accounts) can download.

- Team-based: workspace/project members can download.

- Role-based: roles like Finance or HR can download across teams.

- Share-by-link: a special token grants download, usually with an expiry and scope.

Edge cases need clear rules, not one-off fixes. Decide how admins work (global access or only certain categories), how support gets temporary access (time-boxed and logged), and what happens when a user is deleted (keep files for compliance, reassign ownership, or delete).

Treat metadata and downloads separately

A simple pattern is two checks: (1) can the user read the upload record, (2) can the user request a download response. That second check is where you enforce “private unless allowed,” even if someone guesses an ID.

For sensitive documents, log access. At minimum, record who downloaded (user ID and role), what they downloaded (file ID and type), when it happened (timestamp), why it was allowed (policy result, share token, admin override), and where it came from (IP or device, if appropriate).

In AppMaster, these rules often live in the Business Process Editor: one flow for listing upload metadata, and a stricter flow for generating a download response.

Expiring download links: safer downloads without friction

Expiring download links are a good middle ground between “anyone with the URL can download forever” and “users must log in every time.” They work well for one-off downloads, sharing a document by email, or giving temporary access to a contractor. At scale, they also reduce support issues because you can grant access without opening up your entire storage.

Two common patterns:

- Signed URLs expire automatically. They’re simple and fast, but revocation is hard if the link is already out in the wild.

- A token-based download endpoint gives you more control. The link contains a short token, your app checks permissions on every request, and then serves or redirects to the file.

A practical setup:

- Use short expirations for shared links (10 to 60 minutes) and refresh on demand.

- Keep longer expirations only for trusted, logged-in sessions (for example, “Download again” generates a new link).

- Scope links tightly: one file, one user (or recipient), one action (view vs download).

- Log link creation and usage so you can trace leaks without guessing.

Scope matters because view usually means inline display, while download implies saving a copy. If you need both, create separate links with separate rules.

Plan for revocation. If a user loses access (refund, role change, contract ends), signed URLs alone might not be enough. With a token endpoint, you can invalidate tokens immediately. With signed URLs, keep expirations short and rotate signing keys only when necessary (key rotation revokes everything, so use it carefully).

Example: a customer portal invoice link emailed to an accountant expires in 30 minutes, allows view-only, and is tied to that invoice ID plus the customer account. If the customer is removed from the account, the token is rejected even if the email is forwarded.

Step-by-step: a scalable upload flow

A reliable upload flow separates three concerns: what you allow, where bytes go, and who can fetch them later. When those are mixed together, small edge cases turn into production incidents.

A practical flow for images, PDFs, and most user-generated files:

- Define purpose-based rules. For each purpose (avatar, invoice, ID document), set allowed types, max size, and any extra checks like max pages.

- Create an upload request on your backend. The client asks for permission to upload. The backend returns an upload target (such as an object storage key plus a short-lived token) and creates a new upload row with

pending. - Upload bytes to storage, then confirm. The client uploads to object storage, then calls your backend to confirm completion. The backend checks the expected key and basic properties, then marks the row

uploaded. - Run async verification. In the background, verify the real file type (ideally including magic bytes), enforce size, extract safe metadata (dimensions, page count), and optionally run malware scanning. If it fails, mark the upload

blockedand prevent downloads. - Serve downloads through policy. On download, verify the user has access to the file’s owning entity (user, org, ticket, order). Then proxy the download or return expiring download links to keep storage private.

Add cleanup. Delete abandoned pending uploads after a short window, and remove unreferenced files (for example, a user uploaded an image but never saved the form).

If you build this in AppMaster, model uploads as their own entity with a status field and owner references, then enforce the same permission checks in every download Business Process.

Example: invoices in a customer portal

A customer portal where users upload invoices as PDFs sounds simple until you have thousands of companies, multiple roles, and the same invoice replaced three times.

For storage organization, keep the raw file in a predictable path that matches how people search. For example: invoices/<company_id>/<yyyy-mm>/<upload_id>.pdf. The company and month make cleanup and reporting easier, while upload_id avoids collisions when two files share the same name.

In the database, store metadata that explains what the file is and who can access it:

company_idandbilling_monthuploaded_by_user_idanduploaded_atoriginal_filenameandcontent_typesize_bytesand checksum (optional)- status (active, replaced, quarantined)

Now sharing: a billing manager wants to send one invoice to an external accountant for 24 hours. Instead of changing global permissions, generate an expiring download link tied to that specific invoice, with a strict expiry time and a single purpose (download only). When the accountant clicks it, your app checks the token, confirms it isn’t expired, and then serves the file.

If a user uploads the wrong PDF or replaces a file, don’t overwrite the old object. Mark the previous record as replaced, keep it for audit, and point the invoice entry to the new upload_id. If you need to honor retention rules, you can delete replaced files later with a scheduled job.

When support gets a “cannot download” ticket, metadata helps diagnose quickly: is the link expired, is the invoice marked replaced, does the user belong to the right company, or was the file flagged as quarantined? In AppMaster, these checks can live in a Business Process so every download follows the same rules.

Common mistakes and how to avoid them

When teams first handle file uploads at scale, the bugs are rarely mysterious. They come from a few predictable shortcuts that look fine in a demo and hurt later.

- Trusting only the file extension or only the MIME type. Attackers can rename files, and browsers can lie. Check both, and also verify magic bytes server-side.

- Using public storage and hoping permissions are enough. A public bucket/container turns every missed rule into a data leak. Keep storage private by default and gate access through your app.

- Putting user-provided names in storage paths or URLs. Names like invoice_john_smith.pdf leak personal info and make guessing easier. Use random IDs for object keys, store the display name as metadata.

- Mixing tenant files in the same path without strong checks. A path like /uploads/2026/01/ isn’t a permission model. Always verify tenant and user rights before returning a download.

- Skipping cleanup for failed or abandoned uploads. Multi-part uploads and retries leave junk behind. Add a background job that removes pending uploads that never completed.

One mistake teams forget is having no plan for retries and duplicates. Mobile networks drop. Users tap twice. Your system should treat “upload the same file again” as normal.

A practical approach is to generate an upload ID first, then accept chunks or a single file, and mark the record verified only after validation passes. If the same upload is repeated, return the existing record instead of creating a second copy.

If you build this in AppMaster, keep the core rules in one place (backend logic) so your web and mobile apps behave the same, even when the UI changes.

Quick checklist before you ship

Before you open uploads to real users, do a quick pass on the basics. Most issues with file uploads at scale come from small gaps that only show up after you have many users, many files, and many edge cases.

- Allowlist file types and set size limits per use case (avatars vs invoices). Validate both the extension and the real content type.

- Save upload metadata in your database: who owns it (user, team, account), what it’s for, and a clear status like

pending,verified, orblocked. - Keep storage private by default, and enforce permission checks on every download (don’t rely on hidden URLs).

- Use expiring download links when sharing is needed, and keep lifetimes short (minutes or hours, not days).

- Avoid personal data in paths and filenames. Use random IDs, and show a friendly display name in the UI instead.

Have an answer for abandoned uploads. It’s normal for users to start an upload and never finish, or to replace files often.

A simple cleanup plan:

- Delete orphaned files that never reached

verifiedafter a set time. - Keep a retention window for replaced files, then remove them.

- Log key events (upload, validation, download, delete) so support can investigate.

If you’re building this in AppMaster, store metadata in PostgreSQL via the Data Designer, enforce checks in the Business Process Editor, and generate short-lived download tokens before serving files.

Next steps: ship safely, then improve in small steps

The fastest way to get to a safe release is to pick one upload approach and stick to it. Decide whether files go through your backend first, or upload directly to object storage with a short-lived token. Then write down the exact steps and who owns each one (client, backend, storage). Consistency beats cleverness when you’re dealing with file uploads at scale.

Start with strict defaults. Limit file types to what you truly need, keep size limits conservative, and require authentication for anything that isn’t meant to be public. If users ask for larger files or more formats, loosen one rule at a time and measure the impact.

Add basic monitoring early so problems show up quickly:

- Upload failure rate (by device, browser, and file type)

- Average and p95 upload size

- Time to upload (especially on mobile networks)

- Storage growth per day or per week

- Download errors (including expired or forbidden links)

If this upload system is part of a bigger app, keep the data model and permissions close to your business logic. Teams using AppMaster often put upload records in PostgreSQL, implement validation and file access control in Business Processes, and reuse the same logic across backend, web app, and native mobile apps.

One useful next improvement is adding previews for common formats, audit logs for sensitive documents, or simple retention rules (for example, auto-delete temporary uploads after 30 days). Small, steady upgrades keep the system reliable as usage grows.

FAQ

Start by writing down the real categories you expect: avatars, invoices, contracts, ticket attachments, exports, and so on. For each category, decide who can upload, who can view, who can replace or delete, whether sharing should expire, and how long you keep it. Those decisions drive your database model and permission checks, so you don’t rebuild everything later.

Use an allowlist and check both the filename extension and the detected MIME type from the content. Set clear size limits per file purpose, and add deeper checks where they matter, like image dimensions or PDF page count. Rename files to a generated ID and store the original name as metadata so you avoid collisions and unsafe filenames.

Extensions are easy to fake, and MIME types can be inconsistent across devices and browsers. Checking both catches a lot of obvious spoofing, but for higher-risk uploads you should also verify the file signature (magic bytes) on the server during verification. Treat anything that fails as blocked and prevent downloads until it’s reviewed or removed.

Create a database record first and return an upload ID, then upload the bytes and confirm completion. This prevents “mystery files” in storage with no owner or purpose, and it lets you enforce permissions before any data moves. It also makes cleanup straightforward because you can find abandoned pending uploads reliably.

Make storage private by default and gate access through your app’s permission logic. Keep object keys predictable but not personal, using tenant or workspace IDs plus an opaque upload ID, and store human-friendly details in the database. Separate originals from derivatives like thumbnails so retention and permissions don’t get tangled.

Treat metadata access and byte access as different permissions. Many users can be allowed to see that a file exists without being allowed to download it. Always enforce a deny-by-default rule on downloads, log access for sensitive documents, and avoid “security by unguessable URL” as your main control.

Signed URLs are fast and simple, but once a link is shared you usually can’t revoke it until it expires. A token-based download endpoint lets you check permissions on every request and revoke access immediately by invalidating tokens. In practice, short expirations plus tight scoping to one file and one action reduces risk without adding much friction.

Design for retries as normal behavior: mobile connections drop, users refresh, and uploads get duplicated. Generate an upload ID first, accept the upload against that ID, and make the confirm step idempotent so repeating it doesn’t create extra copies. If you want to reduce duplicates further, store a checksum after upload and detect re-uploads of the same content for the same purpose.

Pending uploads will accumulate when users abandon a form or lose connection, so schedule cleanup from day one. Expire and delete old pending records and their storage objects, and keep blocked items only as long as you need for investigation. For replaced documents, keep a retention window for audit needs, then remove old versions automatically.

Model uploads as their own entity in PostgreSQL with status, owner, scope, and purpose fields, then enforce rules in one backend flow so web and mobile behave the same. Put validation and verification steps into a Business Process so every upload path applies the same allowlist, limits, and status transitions. Serve downloads through a stricter Business Process that checks permissions and issues short-lived download tokens when sharing is needed.