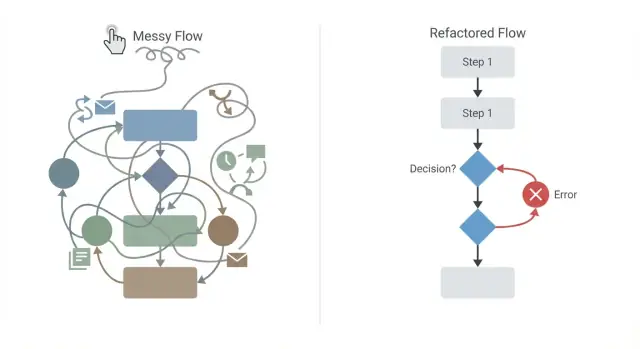

Drag-and-drop process design mistakes and how to refactor

Drag-and-drop process design mistakes can make workflows hard to change and easy to break. Learn common anti-patterns and practical refactoring steps.

Why drag-and-drop workflows go wrong

Visual process editors feel safe because you can see the whole flow. But the diagram can still lie. A workflow can look tidy and fail in production once real users, real data, and real timing issues show up.

A lot of problems come from treating the diagram like a checklist instead of what it really is: a program. Blocks still contain logic. They still create state, branch, retry, and trigger side effects. When those parts aren’t made explicit, “small” edits can quietly change behavior.

A workflow anti-pattern is a repeatable bad shape that keeps causing trouble. It’s not a single bug. It’s a habit, like hiding important state in variables set in one corner of the diagram and used somewhere else, or letting the flow grow until no one can reason about it.

The symptoms are familiar:

- The same input produces different results across runs

- Debugging turns into guesswork because you can’t tell where a value changed

- Small edits break unrelated paths

- Fixes add more branches instead of reducing them

- Failures leave partial updates (some steps succeeded, others didn’t)

Start with what’s cheap and visible: clearer naming, tighter grouping, removing dead paths, and making each step’s inputs and outputs obvious. In platforms like AppMaster, that often means keeping a Business Process focused, so each block does one job and passes data in the open.

Then plan deeper refactors for structural issues: untangling spaghetti flows, centralizing decisions, and adding compensation for partial success. The goal isn’t a prettier diagram. It’s a workflow that behaves the same way every time, and stays safe to change when requirements shift.

Hidden state: the quiet source of surprises

Many visual workflow failures start with one invisible problem: state you rely on, but never clearly name.

State is anything your workflow needs to remember to behave correctly. That includes variables (like customer_id), flags (like is_verified), timers and retries, and also state outside your diagram: a database row, a CRM record, a payment status, or a message that’s already been sent.

Hidden state appears when that “memory” lives somewhere you don’t expect. Common examples are node settings that quietly behave like variables, implicit defaults you never set on purpose, or side effects that change data without making it obvious. A step that “checks” something but also updates a status field is a classic trap.

It often works until you make a small edit. You move a node, reuse a subflow, change a default, or add a new branch. Suddenly the workflow starts behaving “randomly” because a variable gets overwritten, a flag was never reset, or an external system returns a slightly different value.

Where state hides (even in clean-looking diagrams)

State tends to hide in:

- Node settings that act like variables (hardcoded IDs, default statuses)

- Implicit outputs from earlier steps (“use last result”)

- “Read” steps that also write (DB updates, status changes)

- External systems (payments, email/SMS providers, CRMs) that remember past actions

- Timers and retries that keep running after a branch changes

The rule that prevents most surprises

Make state explicit and named. If a value matters later, store it in a clearly named variable, set it in one place, and reset it when you’re done.

For example, in AppMaster’s Business Process Editor, treat every important output as a first-class variable, not something you “know” is available because a node ran earlier. A small change like renaming status to payment_status, and setting it only after a confirmed payment response, can save hours of debugging when the flow changes next month.

Spaghetti flows: when the diagram becomes unreadable

A spaghetti flow is a visual process where connectors cross everywhere, steps loop back in surprising places, and conditions are nested so deep that nobody can explain the happy path without zooming and scrolling. If your diagram feels like a subway map drawn on a napkin, you’re already paying the price.

This makes reviews unreliable. People miss edge cases, approvals take longer, and a change in one corner can break something far away. During an incident, it’s hard to answer basic questions like “Which step ran last?” or “Why did we enter this branch?”

Spaghetti usually grows from good intentions: copy-pasting a working branch “just once,” adding quick fixes under pressure, layering exception handling as nested conditions, jumping backward to earlier steps instead of creating a reusable sub-process, or mixing business rules, data formatting, and notifications inside the same block.

A common example is onboarding. It starts clean, then grows separate branches for free trials, partner referrals, manual review, and “VIP” handling. After a few sprints, the diagram has multiple back-edges to “Collect docs” and several different places that send the welcome email.

A healthier target is simple: one main path for the common case, plus clear side paths for exceptions. In tools like AppMaster’s Business Process Editor, that often means extracting repeated logic into a reusable sub-process, naming branches by intent (“Needs manual review”), and keeping loops explicit and limited.

Decision overload and duplicated rules

A common pattern is a long chain of condition nodes: check A, then check A again later, then check B in three different places. It starts as “just one more rule,” then the workflow becomes a maze where small changes have big side effects.

The bigger risk is scattered rules that slowly disagree. One path approves an application because a credit score is high. Another path blocks the same application because an older step still treats “missing phone number” as a hard stop. Both decisions might be “reasonable” locally, but together they produce inconsistent outcomes.

Why duplicated checks cause conflicts

When the same rule is repeated across the diagram, people update one copy and miss the others. Over time you get checks that look similar but aren’t: one says “country = US,” another says “country in (US, CA),” and a third uses “currency = USD” as a proxy. The workflow still runs, but it stops being predictable.

A good refactor is to consolidate decisions into one clearly named decision step that produces a small set of outcomes. In tools like AppMaster’s Business Process Editor, that often means grouping related checks into a single decision block and making the branches meaningful.

Keep the outcomes simple, for example:

- Approved

- Needs info

- Rejected

- Manual review

Then route everything through that single decision point instead of sprinkling mini-decisions throughout the flow. If a rule changes, you update it once.

A concrete example: a signup verification workflow checks email format in three places (before OTP, after OTP, and before account creation). Move all validation into one “Validate request” decision. If it’s “Needs info,” route to one message step that tells the user exactly what’s missing, instead of failing later with a generic error.

Missing compensation steps after partial success

One of the most expensive mistakes is assuming every workflow either fully succeeds or fully fails. Real flows often succeed halfway. If a later step breaks, you’re left with a mess: money captured, messages sent, records created, but no clean way to back out.

Example: you charge a customer’s card, then try to create the order. The payment succeeds, but order creation fails because an inventory service times out. Now support gets the angry email, finance sees the charge, and your system has no matching order to fulfill.

Compensation is the “undo” (or “make it safe”) path that runs when something fails after partial success. It doesn’t need to be perfect, but it must be intentional. Typical approaches include reversing the action (refund, cancel, delete a draft), converting the result into a safe state (mark “Payment captured, fulfillment pending”), routing to manual review with context, and using idempotency checks so retries don’t double-charge or double-send.

Where you place compensation matters. Don’t hide all cleanup in a single “error” box at the end of the diagram. Put it next to the risky step, while you still have the data you need (payment ID, reservation token, external request ID). In tools like AppMaster, that usually means saving those IDs right after the call, then branching immediately on success vs failure.

A useful rule: every step that talks to an external system should answer two questions before you move on: “What did we change?” and “How do we undo or contain it if the next step fails?”

Weak error handling around external calls

Many failures show up the moment your workflow leaves your system. External calls fail in messy ways: slow responses, temporary outages, duplicate requests, and partial success. If your diagram assumes “call succeeded” and keeps going, users eventually see missing data, double charges, or notifications sent at the wrong time.

Start by marking steps that can fail for reasons you don’t control: external APIs, payments and refunds (for example, Stripe), messages (email/SMS, Telegram), file operations, and cloud services.

Two traps are especially common: missing timeouts and blind retries. Without a timeout, one slow request can freeze the whole process. With retries but no rules, you can make things worse, like sending the same message three times or creating duplicates in a third-party system.

This is where idempotency matters. In plain terms, an idempotent action is safe to run again. If the workflow repeats a step, it shouldn’t create a second charge, a second order, or a second “welcome” message.

A practical fix is to store a request key and a status before you call out. In AppMaster’s Business Process Editor, that can be as simple as writing a record like “payment_attempt: key=XYZ, status=pending,” then updating it to “success” or “failed” after the response. If the workflow hits the step again, check that record first and decide what to do.

A reliable pattern looks like this:

- Set a timeout and retry limits (and define what errors are retryable)

- Save a request key and current status before the call

- Make the external call

- On success, write the result and mark status as completed

- On failure, log the error and route to a user-friendly recovery path

Overloaded steps and unclear responsibilities

A common mistake is building a single step that quietly does four jobs: validate input, calculate values, write to the database, and notify people. It feels efficient, but it makes changes risky. When something breaks, you don’t know which part caused it, and you can’t safely reuse it elsewhere.

How to spot an overloaded step

A step is overloaded when its name is vague (like “Handle order”) and you can’t describe its output in one sentence. Another red flag is a long list of inputs that are only used by “some part” of the step.

Overloaded steps often mix:

- Validation and mutation (save/update)

- Business rules and presentation (formatting messages)

- Multiple external calls in one place

- Several side effects without a clear order

- Unclear success criteria (what does “done” mean?)

Refactor into small blocks with clear contracts

Split the big step into smaller, named blocks where each block has one job and a clear input and output. A simple naming pattern helps: verbs for steps (Validate Address, Calculate Total, Create Invoice, Send Confirmation) and nouns for data objects.

Use consistent names for inputs and outputs, too. For example, prefer “OrderDraft” (before saving) and “OrderRecord” (after saving) rather than “order1/order2” or “payload/result”. It makes the diagram readable even months later.

When you repeat a pattern, extract it into a reusable subflow. In AppMaster’s Business Process Editor, this often looks like moving “Validate -> Normalize -> Persist” into a shared block used by multiple workflows.

Example: an onboarding workflow that “creates user, sets permissions, sends email, and logs audit” can become four steps plus a reusable “Write Audit Event” subflow. That makes testing simpler, edits safer, and surprises rarer.

How to refactor a messy workflow step by step

Most workflow problems come from adding “just one more” rule or connector until nobody can predict what happens. Refactoring is about making the flow readable again, and making every side effect and failure case visible.

Start by drawing the happy path as one clear line from start to finish. If the main goal is “approve an order,” that line should show only the essential steps needed when everything goes right.

Then work in small passes:

- Redraw the happy path as a single forward path with consistent step names (verb + object)

- List every side effect (sending emails, charging cards, creating records) and make each one its own explicit step

- For each side effect, add its failure path right next to it, including compensation when you already changed something

- Replace repeated conditions with one decision point and route from there

- Extract repeated chunks into subflows, and rename variables so their meaning is obvious (

payment_statusbeatsflag2)

A fast way to spot hidden complexity is to ask: “If this step runs twice, what breaks?” If the answer is “we might double-charge” or “we might send two emails,” you need clearer state and idempotent behavior.

Example: an onboarding workflow creates an account, assigns a plan, charges Stripe, and sends a welcome message. If charging succeeds but the welcome message fails, you don’t want a paid user stuck with no access. Add a nearby compensation branch: mark the user as pending_welcome, retry messaging, and if retries fail, refund and revert the plan.

In AppMaster, this cleanup is easier when you keep the Business Process Editor flow shallow: small steps, clear variable names, and subflows for “Charge payment” or “Send notification” that you can reuse everywhere.

Common refactoring traps to avoid

Refactoring visual workflows should make the process easier to understand and safer to change. But some fixes add new complexity, especially under time pressure.

One trap is keeping old paths alive “just in case” with no clear switch, version marker, or retirement date. People keep testing the old route, support keeps referencing it, and soon you’re maintaining two processes. If you need a gradual rollout, make it explicit: name the new path, gate it with one visible decision, and plan when the old one will be deleted.

Temporary flags are another slow leak. A flag created for debugging or a one-week migration often becomes permanent, and every new change has to consider it. Treat flags like perishable items: document why they exist, name an owner, and set a removal date.

A third trap is adding one-off exceptions instead of changing the model. If you keep inserting “special case” nodes, the diagram grows sideways and rules become impossible to predict. When the same exception shows up twice, it usually means the data model or the process states need an update.

Finally, don’t hide business rules inside unrelated nodes just to make it work. It’s tempting, especially in visual editors, but later nobody can find the rule.

Warning signs:

- Two paths that do the same job with small differences

- Flags with unclear meaning (like “temp2” or “useNewLogic”)

- Exceptions that only one person can explain

- Rules split across many nodes without a clear source of truth

- “Fix” nodes added after failures instead of improving the earlier step

Example: if VIP customers need a different approval, don’t add hidden checks in three places. Add a clear “Customer type” decision once, and route from there.

Quick checklist before you ship

Most issues show up right before launch: someone runs the flow with real data, and the diagram does something nobody can explain.

Do a walkthrough out loud. If the happy path needs a long story, the flow probably has hidden state, duplicated rules, or too many branches that should be grouped.

A quick pre-ship check

- Explain the happy path in one breath: trigger, main steps, finish line

- Make every side effect its own visible step (charging, sending messages, updating records, creating tickets)

- For each side effect, decide what happens on failure and how you undo partial success (refund, cancel, rollback, or mark for manual review)

- Check variables and flags: clear names, one obvious place where each is set, and no mystery defaults

- Hunt for copy-paste logic: the same check in multiple branches, or the same mapping repeated with small changes

One simple test that catches most issues

Run the flow with three cases: a normal success, a likely failure (like a payment decline), and a weird edge case (missing optional data). Watch for any step that “sort of works” and leaves the system half-done.

In a tool like AppMaster’s Business Process Editor, this often turns into a clean refactor: pull repeated checks into one shared step, make side effects explicit nodes, and add a clear compensation path right next to each risky call.

A realistic example: onboarding flow refactor

Imagine a customer onboarding workflow that does three things: verifies the user’s identity, creates their account, and starts a paid subscription. It sounds simple, but it often becomes a flow that “usually works” until something fails.

The messy version

The first version grows step by step. A “Verified” checkbox gets added, then a “NeedsReview” flag, then more flags. Checks like “if verified” appear in several places because each new feature adds its own branch.

Soon the workflow looks like this: verify identity, create user, charge card, send welcome email, create workspace, then jump back to re-check verification because a later step depends on it. If charging succeeds but workspace creation fails, there’s no rollback. The customer is billed, but their account is half-created, and support tickets follow.

The refactor

A cleaner design starts by making state visible and controlled. Replace scattered flags with a single explicit onboarding status (for example: Draft, Verified, Subscribed, Active, Failed). Then put the “should we continue?” logic in one decision point.

Refactor goals that usually fix the pain fast:

- One decision gate that reads the explicit status and routes the next step

- No repeated checks across the diagram, only reusable validation blocks

- Compensation for partial success (refund payment, cancel subscription, delete workspace draft)

- A clear failed path that records why, then stops safely

After that, model the data and workflow together. If “Subscribed” is true, store the subscription ID, payment ID, and provider response in one place so compensation can run without guessing.

Finally, test failure cases on purpose: verification timeouts, payment success but email failure, workspace creation errors, and duplicate webhook events.

If you’re building these workflows in AppMaster, it helps to keep business logic in reusable Business Processes and let the platform regenerate clean code as requirements change, so old branches don’t linger. If you want to prototype the refactor quickly (with backend, web, and mobile pieces in one place), AppMaster on appmaster.io is designed for exactly this kind of end-to-end workflow build.