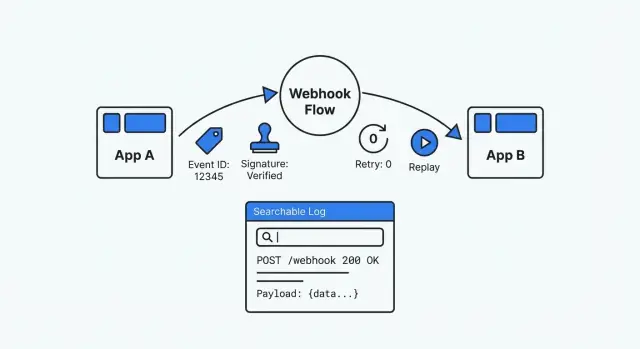

Debug webhook integrations: signatures, retries, replay, event logs

Learn to debug webhook integrations by standardizing signatures, handling retries safely, enabling replay, and keeping event logs that are easy to search.

Why webhook integrations turn into a black box

A webhook is just one app calling your app when something happens. A payment provider tells you “payment succeeded”, a form tool says “new submission”, or a CRM reports “deal updated”. It feels simple until something breaks and you realize there’s no screen to open, no obvious history, and no safe way to replay what happened.

That’s why webhook issues are so frustrating. The request arrives (or doesn’t). Your system processes it (or fails). The first signal is often a vague ticket like “customers can’t check out” or “the status didn’t update”. If the provider retries, you might get duplicates. If they change a payload field, your parser can break for only some accounts.

Common symptoms:

- “Missing” events where you can’t tell if they were never sent or just not processed

- Duplicate deliveries that create duplicate side effects (two invoices, two emails, two status changes)

- Payload changes (new fields, missing fields, wrong types) that only fail sometimes

- Signature checks that pass in one environment and fail in another

A debuggable webhook setup is the opposite of guesswork. It’s traceable (you can find every delivery and what you did with it), repeatable (you can safely replay a past event), and verifiable (you can prove authenticity and processing results). When someone asks “what happened to this event?”, you should be able to answer with evidence in minutes.

If you build apps on a platform like AppMaster, this mindset matters even more. Visual logic is quick to change, but you still need a clear event history and safe replay so external systems never become a black box.

The minimum data you need to make webhooks observable

When you’re debugging under pressure, you need the same basics every time: a record you can trust, search, and replay. Without that, every webhook becomes a one-off mystery.

Decide what a single webhook “event” means in your system. Treat it like a receipt: one incoming request equals one stored event, even if processing happens later.

At minimum, store:

- Event ID: use the provider’s ID when available; otherwise generate one.

- Trusted receipt data: when you received it, and what sent it (provider name, endpoint, IP if you keep it). Keep

received_atseparate from timestamps inside the payload. - Processing status plus a reason: use a small set of states (received, verified, handled, failed) and store a short failure reason.

- Raw request and a parsed view: save raw body and headers exactly as received (for audits and signature checks), plus a parsed JSON view for search and support.

- Correlation keys: one or two fields you can search by (order_id, invoice_id, user_id, ticket_id).

Example: a payments provider sends “payment_succeeded” but your customer still shows unpaid. If your event log includes the raw request, you can confirm the signature and see the exact amount and currency. If it also includes invoice_id, support can find the event from the invoice, see it’s stuck in “failed”, and hand engineering a clear error reason.

In AppMaster, one practical approach is a “WebhookEvent” table in the Data Designer, with a Business Process updating status as each step completes. The tool isn’t the point. The consistent record is.

Standardize event structure so logs are readable

If every provider sends a different payload shape, your logs will always feel messy. A stable event “envelope” makes debugging faster because you can scan for the same fields every time, even when the data changes.

A useful envelope typically includes:

id(unique event id)type(clear event name likeinvoice.paid)created_at(when the event happened, not when you received it)data(the business payload)version(likev1)

Here’s a simple example you can log and store as-is:

{

"id": "evt_01H...",

"type": "payment.failed",

"created_at": "2026-01-25T10:12:30Z",

"version": "v1",

"correlation": {"order_id": "A-10492", "customer_id": "C-883"},

"data": {"amount": 4990, "currency": "USD", "reason": "insufficient_funds"}

}

Pick one naming style (snake_case or camelCase) and stick to it. Be strict about types too: don’t make amount a string sometimes and a number other times.

Versioning is your safety net. When you need to change fields, publish v2 while keeping v1 working for a while. It prevents support incidents and makes upgrades much easier to debug.

Signature verification that is consistent and testable

Signatures keep your webhook endpoint from becoming an open door. Without verification, anyone who learns your URL can send fake events, and attackers can try to tamper with real requests.

The most common pattern is an HMAC signature with a shared secret. The sender signs the raw request body (best) or a canonical string. You recompute the HMAC and compare. Many providers include a timestamp in what they sign so captured requests can’t be replayed later.

A verification routine should be boring and consistent:

- Read the raw body exactly as received (before JSON parsing).

- Recompute the signature using the provider’s algorithm and your secret.

- Compare with a constant-time function.

- Reject old timestamps (use a short window, like a few minutes).

- Fail closed: if anything is missing or malformed, treat it as invalid.

Make it testable. Put verification in one small function and write tests with known-good and known-bad samples. A common time sink is signing parsed JSON instead of raw bytes.

Plan for secret rotation from day one. Support two active secrets during transitions: try the newest first, then fall back to the previous secret.

When verification fails, log enough to debug without leaking secrets: provider name, timestamp (and whether it was too old), signature version, request/correlation ID, and a short hash of the raw body (not the body itself).

Retries and idempotency without duplicate side effects

Retries are normal. Providers retry on timeouts, network hiccups, or 5xx responses. Even if your system did the work, the provider may not have received your response in time, so the same event can show up again.

Decide up front what responses mean “retry” vs “stop”. Many teams use rules like:

- 2xx: accepted, stop retrying

- 4xx: configuration or request problem, usually stop retrying

- 408/429/5xx: temporary failure or rate limit, retry

Idempotency means you can safely handle the same event more than once without repeating side effects (charging twice, creating duplicate orders, sending two emails). Treat webhooks as at-least-once delivery.

A practical pattern is to store each incoming event’s unique ID with the outcome of processing. On repeat delivery:

- If it was successful, return 2xx and do nothing.

- If it failed, retry internal processing (or return a retryable status).

- If it’s in progress, avoid parallel work and return a short “accepted” response.

For internal retries, use exponential backoff and cap attempts. After the cap, move the event to a “needs review” state with the last error. In AppMaster, this maps cleanly to a small table for event IDs and statuses, plus a Business Process that schedules retries and routes repeated failures.

Replay tools that help support teams fix issues fast

Retries are automatic. Replay is intentional.

A replay tool turns “we think it sent” into a repeatable test with the exact same payload. It’s also only safe when two things are true: idempotency and an audit trail. Idempotency prevents double charging, double shipping, or double emailing. The audit trail shows what was replayed, by whom, and what happened.

Single-event replay vs time-range replay

Single-event replay is the common support case: one customer, one failed event, re-deliver it after a fix. Time-range replay is for incidents: a provider outage in a specific window and you need to re-send everything that failed.

Keep selection simple: filter by event type, time range, and status (failed, timed out, or delivered but unacknowledged), then replay one event or a batch.

Guardrails that prevent accidents

Replay should be powerful, but not dangerous. A few guardrails help:

- Role-based access

- Rate limits per destination

- Required reason note stored with the audit record

- Optional approval for large batch replays

- A dry-run mode that validates without sending

After replay, show results next to the original event: success, still failing (with the latest error), or ignored (duplicate detected via idempotency).

Event logs that are useful during incidents

When a webhook breaks during an incident, you need answers in minutes. A good log tells a clear story: what arrived, what you did with it, and where it stopped.

Store the raw request exactly as received: timestamp, path, method, headers, and raw body. That raw payload is your ground truth when vendors change fields or your parser misreads data. Mask sensitive values before saving (authorization headers, tokens, and any personal or payment data you don’t need).

Raw data alone isn’t enough. Also store a parsed, searchable view: event type, external event ID, customer/account identifiers, related object IDs (invoice_id, order_id), and your internal correlation ID. This is what lets support find “all events for customer 8142” without opening every payload.

During processing, keep a short step timeline with consistent wording, for example: “validated signature”, “mapped fields”, “checked idempotency”, “updated records”, “queued follow-ups”.

Retention matters. Keep enough history to cover real delays and disputes, but don’t hoard indefinitely. Consider deleting or anonymizing raw payloads first while keeping lightweight metadata longer.

Step-by-step: build a debuggable webhook pipeline

Build the receiver like a small pipeline with clear checkpoints. Every request becomes a stored event, every processing run becomes an attempt, and every failure becomes searchable.

Receiver pipeline

Treat the HTTP endpoint as intake only. Do the minimum work up front, then move processing to a worker so timeouts don’t turn into mystery behavior.

- Capture headers, raw body, receipt timestamp, and provider.

- Verify the signature (or store a clear “failed verification” status).

- Enqueue processing keyed by a stable event ID.

- Process in a worker with idempotency checks and business actions.

- Record the final result (success/failure) and a useful error message.

In practice, you’ll want two core records: one row per webhook event, and one row per processing attempt.

A solid event model includes: event_id, provider, received_at, signature_status, payload_hash, payload_json (or raw payload), current_status, last_error, next_retry_at. Attempt records can store: attempt_number, started_at, finished_at, http_status (if applicable), error_code, error_text.

Once the data exists, add a small admin page so support can search by event ID, customer ID, or time range, and filter by status. Keep it boring and fast.

Set alerts on patterns, not one-off failures. For example: “provider failed 10 times in 5 minutes” or “event stuck in failed”.

Sender expectations

If you control the sending side, standardize three things: always include an event ID, always sign the payload the same way, and publish a retry policy in plain language. It prevents endless back-and-forth when a partner says “we sent it” and your system shows nothing.

Example: payments webhook from 'failed' to 'fixed' with replay

A common pattern is a Stripe webhook that does two things: creates an Order record, then sends a receipt via email/SMS. It sounds simple until one event fails and nobody knows whether the customer was charged, whether the order exists, or whether the receipt went out.

Here’s a realistic failure: you rotate your Stripe signing secret. For a few minutes, your endpoint still verifies with the old secret, so Stripe delivers events but your server rejects them with a 401/400. The dashboard shows “webhook failed”, while your app logs only say “invalid signature”.

Good logs make the cause obvious. For the failed event, the record should show a stable event ID plus enough verification detail to pinpoint the mismatch: signature version, signature timestamp, verification result, and a clear reject reason (wrong secret vs timestamp drift). During rotation, it also helps to log which secret was attempted (for example “current” vs “previous”), not the raw secret.

Once the secret is fixed and both “current” and “previous” are accepted for a short window, you still have to handle the backlog. A replay tool turns that into a quick task:

- Find the event by event_id.

- Confirm the failure reason is resolved.

- Replay the event.

- Verify idempotency: the Order is created once, the receipt is sent once.

- Add the replay result and timestamps to the ticket.

Common mistakes and how to avoid them

Most webhook problems feel mysterious because systems only record the final error. Treat every delivery like a small incident report: what arrived, what you decided, and what happened next.

A few mistakes show up over and over:

- Logging only exceptions instead of the full lifecycle (received, verified, queued, processed, failed, retried)

- Saving full payloads and headers without masking, then discovering you captured secrets or personal data

- Handling retries like brand-new events, causing double charges or duplicate messages

- Returning 200 OK before the event is durably stored, so dashboards look green while work dies later

Practical fixes:

- Store a minimal, searchable request record plus status changes.

- Mask sensitive fields by default and restrict access to raw payloads.

- Enforce idempotency at the database level, not only in code.

- Acknowledge only after the event is safely stored.

- Build replay as a supported flow, not a one-off script.

If you’re using AppMaster, these pieces fit naturally into the platform: an event table in the Data Designer, a status-driven Business Process for verification and processing, and an admin UI for search and replay.

Quick checklist and next steps

Aim for the same basics every time:

- Every event has a unique event_id, and you store the raw payload as received.

- Signature verification runs on every request, and failures include a clear reason.

- Retries are predictable, and handlers are idempotent.

- Replay is restricted to authorized roles and leaves an audit trail.

- Logs are searchable by event_id, provider id, status, and time, with a short “what happened” summary.

Missing just one of these can still turn an integration into a black box. If you don’t store the raw payload, you can’t prove what the provider sent. If signature failures aren’t specific, you’ll waste hours arguing about whose fault it is.

If you want to build this quickly without hand-coding every component, AppMaster (appmaster.io) can help you assemble the data model, processing flows, and admin UI in one place, while still generating real source code for the final app.