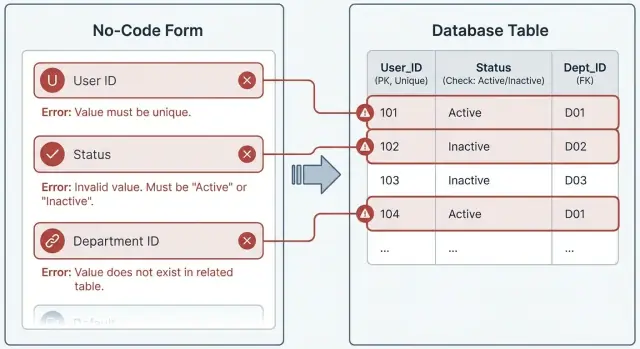

Database constraints for form validation in no-code apps

Use database constraints for form validation to block bad data early, show clear errors, and keep no-code apps consistent across teams.

Why bad form data spreads so quickly

Bad data rarely stays in one place. One wrong value entered in a form can get copied, referenced, and trusted by every part of the app that touches it.

It often starts small: someone types an email with a trailing space, selects the wrong customer, or enters a negative quantity because the field allows it. The form accepts it, so the system treats it as true.

After that, the ripple happens fast. Reports show the wrong totals, automations run on the wrong records, and customer messages pull messy fields and look unprofessional. Teams then create workarounds like private spreadsheets, which creates even more mismatch. Worst of all, the same bad value often comes back later because it appears as an option or gets copied into new records.

Fixing data later is slow and risky because cleanup is rarely one edit. You have to find every place the bad value traveled, update related records, and re-check anything that depends on it. One “simple” correction can break workflows, trigger duplicate notifications, or muddy audit history.

The point of database constraints for form validation is to stop that chain reaction at the first step. When the database refuses impossible or inconsistent data, you prevent silent failures and get a clear moment to show helpful feedback in the UI.

Picture an internal order form built in a no-code tool like AppMaster. If an order is saved with a missing customer link or a duplicate order number, it can poison invoices, shipping tasks, and revenue reports. Catching it at submit time keeps everything downstream clean and saves painful cleanup later.

Database constraints, explained without jargon

Database constraints are simple rules that live in the database. They run every time data is saved, no matter where it comes from: a web form, a mobile screen, an import, or an API call. If a rule is broken, the database refuses the save.

That’s the big difference from UI-only validation. A form can check fields before you hit Save, but those checks are easy to miss or bypass. Another screen might forget the same rule. An automation might write directly to the database. Soon you have data that looks fine in one place and breaks reports in another.

When people talk about database constraints for form validation, they mean this: let the database be the final judge, and let the UI guide the user so they rarely hit that wall.

Most real apps can cover a lot of ground with three basics:

- Unique: “This value must be one of a kind.” Example: email, employee ID, invoice number.

- Check: “This condition must be true.” Example: quantity > 0, start_date <= end_date.

- Foreign key: “This must point to a real record in another table.” Example: every order must reference an existing customer.

Constraints matter even more in no-code apps because you usually have more than one way to create or update data. You might have a web app for admins, a mobile app for field staff, and automated processes writing records behind the scenes. Constraints keep all of those paths consistent.

They also make errors clearer when you design for them. Instead of letting bad data slip in and fixing it later, you can show a focused message like “That invoice number already exists” or “Please select a valid customer” and keep the database clean from day one.

From constraint to clear, human error messages

Constraints are great at stopping bad data, but raw database errors are usually written for developers, not for the person filling out a form. The goal is simple: keep the rule in the database, then translate the failure into a message that explains what happened and what to do next.

Treat each constraint as a small “error contract” with two parts: what’s wrong, and how to fix it. Your UI stays friendly without weakening the data rules.

A few translations that work well:

-

Bad: “Unique constraint violation on users_email_key”

-

Good: “This email is already in use. Try signing in or use a different email.”

-

Bad: “Check constraint failed: order_total_positive”

-

Good: “Total must be greater than 0. Add at least one item or adjust the quantity.”

-

Bad: “Foreign key violation on customer_id”

-

Good: “Choose a valid customer. If they’re new, create the customer first.”

Where you show the message matters as much as the words. Put a single-field error right next to the field. For cross-field rules (like “end date must be after start date”), a form-level banner is often clearer.

Keep the set of message styles small. Inline field text for most issues, a small banner for cross-field rules, and a toast for short confirmations (not detailed fixes) is usually enough.

Also keep wording consistent across web and mobile. If your web form says “Choose a valid customer,” your mobile app shouldn’t say “Invalid FK.” Use the same short verbs (“Choose,” “Enter,” “Remove”) and the same tone, so users learn what to expect.

If you’re building in AppMaster, this mapping is something you design intentionally: the database stays strict, while the UI logic turns failures into calm, specific guidance.

Step-by-step: build the rules first, then the form

If you design the form first, you end up chasing edge cases forever. If you design the data rules first, the UI becomes simpler because it’s reflecting rules that already exist in the database.

A practical build order:

- Write down the few fields that really matter. Define “valid” in plain words. Example: “Email must be unique,” “Quantity must be 1 or more,” “Every order must belong to a customer.”

- Model the tables and relationships. Decide what belongs to what before drawing screens.

- Add constraints for the non-negotiable rules. Use unique constraints for duplicates, check constraints for must-always-be-true rules, and foreign keys for relationships.

- Build the UI to match the constraints. Mark required fields, use the right input types, and add simple hints. The UI should guide people, but the database stays the final gate.

- Try to break it on purpose. Paste messy values, attempt duplicates, and select missing related records. Then improve labels and error text until it’s obvious what to fix.

Quick example

Say you’re building an internal “New Order” form. You might let a user search by customer name, but the database should only accept a real Customer ID (foreign key). In the UI, that becomes a searchable picker. If the user submits without picking a customer, the message can simply say “Choose a customer” instead of failing later with a confusing save error.

This keeps rules consistent across web and mobile forms without repeating fragile logic everywhere.

Unique constraints that prevent duplicates people actually create

A unique constraint is the simplest way to stop “same thing, different entry” from piling up. It makes the database refuse a duplicate value, even if the form missed it.

Use unique constraints for values people naturally repeat by accident: emails, usernames, invoice numbers, asset tags, employee IDs, or ticket numbers pasted from spreadsheets.

The first decision is scope. Some values must be unique across the whole system (a username). Others only need to be unique inside a parent group (an invoice number per organization, or an asset tag per warehouse). Choose the scope on purpose so you don’t block valid data.

A practical way to think about it:

- Global unique: one value, one record anywhere (username, public handle)

- Per-organization unique: unique within a company/team (invoice_number + org_id)

- Per-location unique: unique within a site (asset_tag + location_id)

How you handle the conflict matters as much as the rule. When a unique constraint fails, don’t just say “already exists.” Say what collided and what the user can do next. For example: “Invoice number 1047 already exists for Acme Co. Try 1047-2, or open the existing invoice.” If your UI can safely reference the existing record, a small hint like created date or owner can help the user recover without exposing sensitive details.

Edits need special care. A common mistake is treating an update like a new record and flagging a “duplicate” against itself. Make sure your save logic recognizes the current record so it doesn’t compare the row to itself.

In AppMaster, define the unique rule in the Data Designer first, then mirror it in the form with a friendly message. The database remains the final gatekeeper, and your UI stays honest because it’s explaining a real rule.

Check constraints for rules that must always be true

A check constraint is a rule the database enforces on every row, every time. If someone enters a value that breaks the rule, the save fails. This is exactly what you want for rules that should never be violated, even if data is created from different screens, imports, or automations.

The best checks are simple and predictable. If a user can’t guess the rule, they’ll keep hitting errors and blame the form. Keep checks focused on facts, not complicated policy.

Common check constraints that pay off quickly:

- Ranges: quantity between 1 and 1000, age between 13 and 120

- Allowed states: status must be Draft, Submitted, Approved, or Rejected

- Positive numbers: amount > 0, discount between 0 and 100

- Date order: end_date >= start_date

- Simple logic: if status = Approved then approved_at is not null

The trick that makes checks feel friendly is how you phrase the UI message. Don’t echo the constraint name. Tell the user what to change.

Good patterns:

- “Quantity must be between 1 and 1000.”

- “Choose a status: Draft, Submitted, Approved, or Rejected.”

- “End date must be the same as or later than the start date.”

- “Amount must be greater than 0.”

In a no-code builder like AppMaster, it’s fine to mirror the same checks in the form for instant feedback, but keep the database check constraint as the final guardrail. That way, if a new screen is added later, the rule still holds.

Foreign keys that keep relationships real

A foreign key (FK) enforces a simple promise: if a field says it points to another record, that other record must exist. If an Order has a CustomerId, the database refuses any order that references a customer that isn’t in the Customers table.

This matters because relationship fields are where “almost correct” data shows up. Someone types a customer name slightly wrong, pastes an old ID, or selects a record that was deleted yesterday. Without an FK, those mistakes look fine until reporting, invoicing, or support work breaks.

The UI pattern is straightforward: replace free text with safe choices. Instead of a text input for “Customer,” use a select, search, or autocomplete that writes the customer’s ID behind the scenes. In a no-code builder (for example, using AppMaster UI components tied to your models), that usually means binding a dropdown or search list to the Customers table and saving the selected record reference, not the label.

When the referenced record is missing or deleted, decide the behavior upfront. Most teams land on one of these approaches:

- Prevent deletion while related records exist (common for customers, products, departments)

- Archive instead of deleting (keep history without breaking relationships)

- Cascade delete only when it’s truly safe (rare for business data)

- Set the reference to empty only when the relationship is optional

Also plan the “create related record” flow. A form shouldn’t force users to leave, create a customer somewhere else, then come back and retype everything. A practical approach is a “New customer” action that creates the customer first, then returns the new ID and selects it automatically.

If an FK fails, don’t show a raw database message. Say what happened in plain language: “Please choose an existing customer (the selected customer no longer exists).” That single sentence prevents a broken relationship from spreading.

Handling constraint failures in the UI flow

Good forms catch mistakes early, but they shouldn’t pretend they’re the final judge. The UI helps the user move faster; the database guarantees nothing bad gets saved.

Client-side checks are for the obvious stuff: a required field is empty, an email is missing the @, or a number is wildly out of range. Showing those immediately makes the form feel responsive and reduces failed submissions.

Server-side checks are where constraints do their real work. Even if the UI misses something (or two people submit at the same time), the database blocks duplicates, invalid values, and broken relationships.

When a constraint error comes back from the server, keep the response predictable:

- Keep all user input in the form. Don’t reset the page.

- Highlight the field that caused the issue and add a short message nearby.

- If the issue involves multiple fields, show a top message and still mark the best matching field.

- Offer a safe next action: edit the value, or open the existing record if that makes sense.

Finally, log what happened so you can improve the form. Capture the constraint name, the table/field, and the user action that triggered it. If one constraint fails often, add a small hint in the UI or an extra client-side check. A sudden spike can also signal a confusing screen or a broken integration.

Example: an internal order form that stays clean over time

Consider a simple internal tool used by sales and support: a “Create Order” form. It looks harmless, but it touches the most important tables in your database. If the form accepts bad inputs even once, those mistakes spread into invoices, shipping, refunds, and reports.

The clean way to build it is to let database rules lead the UI. The form becomes a friendly front end for rules that keep holding up, even when someone imports data or edits records elsewhere.

Here’s what the Order table enforces:

- Unique order number: each

order_numbermust be different. - Checks for always-true rules:

quantity > 0,unit_price >= 0, and maybeunit_price <= 100000. - Foreign key to Customer: every order must point to a real customer record.

Now see what happens in real use.

A rep types an order number from memory and accidentally reuses one. The save fails on the unique constraint. Instead of a vague “save failed,” the UI can show: “Order number already exists. Use the next available number or search the existing order.”

Later, a customer record is merged or deleted while someone still has the form open. They hit Save with the old customer selected. The foreign key blocks it. A good UI response is: “That customer is no longer available. Refresh the customer list and choose another.” Then you reload the Customer dropdown and keep the rest of the form intact so the user doesn’t lose their work.

Over time, this pattern keeps orders consistent without relying on everyone to be careful every day.

Common mistakes that cause confusing errors and dirty data

The fastest way to get messy data is to rely on UI-only rules. A required field in a form helps, but it doesn’t protect imports, integrations, admin edits, or a second screen that writes to the same table. If the database accepts bad values, they’ll show up everywhere later.

Another common mistake is writing constraints that are too strict for real life. A check that sounds correct on day one can block normal use cases a week later, like refunds, partial shipments, or phone numbers from other countries. A good rule is: constrain what must always be true, not what is usually true.

Updates often get overlooked. Unique collisions on edit are classic: a user opens a record, changes an unrelated field, and the save fails because a “unique” value changed elsewhere. Status transitions are another trap. If a record can move from Draft to Approved to Cancelled, make sure your checks allow the full path, not just the final state.

Foreign keys fail in the most avoidable way: letting people type IDs. If the UI allows free text for a related record, you’ll end up with broken relationships. Prefer selectors that bind to existing records, then keep the foreign key in the database as the final guard.

Finally, raw database errors create panic and support tickets. You can keep strict constraints and still show human messages.

A short fix list:

- Keep constraints as the source of truth, not just form rules

- Design checks around real workflows, including exceptions

- Handle edits and transitions, not only “create”

- Use pickers for relationships, not typed identifiers

- Map constraint failures to friendly, field-level messages

Quick checklist and next steps for no-code teams

Before you ship a form, assume it’ll be used in a hurry, on a bad day, with copied data. The safest approach is database constraints for form validation, so the database enforces the truth even if the UI misses something.

Quick checks before launch

Run these checks on every form that writes to your database:

- Duplicates: identify what must be unique (email, order number, external ID) and confirm the unique rule exists

- Missing relations: confirm every required relationship is enforced (for example, an Order must have a Customer)

- Invalid ranges: add checks for values that must stay within bounds (quantity > 0, discount between 0 and 100)

- Required fields: ensure “must have” data is enforced at the database level, not only with UI required flags

- Safe defaults: decide what should auto-fill (status = "Draft") so people don’t guess

Then test like a user, not like a builder: do one clean submission end-to-end, then try to break it with duplicates, missing relations, out-of-range numbers, blank required fields, and wrong-type inputs.

Next steps in AppMaster

If you’re building on AppMaster (appmaster.io), model the rules first in the Data Designer (unique, check, and foreign keys), then build the form in the web or mobile UI builder and connect the save logic in the Business Process Editor. When a constraint fails, catch the error and map it to one clear action: what to change and where.

Keep error text consistent and calm. Avoid blame. Prefer “Use a unique email address” over “Email is invalid.” If you can, show the conflicting value or the required range so the fix is obvious.

Pick one real form (like “Create Customer” or “New Order”), build it end-to-end, then validate it with messy sample data from your team’s day-to-day work.

FAQ

Start with database constraints because they protect every write path: web forms, mobile screens, imports, and API calls. UI validation is still useful for faster feedback, but the database should be the final gate so bad values can’t sneak in through a different screen or automation.

Focus on the basics that stop most real-world data damage: unique for duplicates, check for must-always-be-true rules, and foreign keys for real relationships. Add only the rules you’re confident should never be violated, even during imports or edge cases.

Use a unique constraint when a value should identify one record within the chosen scope, like an email, invoice number, or employee ID. Decide the scope first (global vs per organization/location) so you don’t block valid repeats that are normal in your business.

Keep check constraints simple and predictable, like ranges, positive numbers, or date ordering. If users can’t guess the rule from the field label, they’ll hit errors repeatedly, so phrase the UI guidance clearly and avoid checks that encode complicated policy.

A foreign key prevents “almost correct” references, like an order pointing to a customer that doesn’t exist anymore. In the UI, avoid free-text relationship fields; use a picker or search that saves the related record’s ID so the relationship stays valid.

Treat each constraint like an “error contract”: translate the technical failure into a sentence that says what happened and what to do next. For example, replace a raw unique violation with “This email is already in use. Use a different email or sign in.”

Show single-field errors right next to the field and keep the user’s input intact so they can fix it quickly. For cross-field rules (like start/end dates), use a short form-level message and still highlight the most relevant field so the fix is obvious.

Client-side checks should catch obvious issues early (empty required fields, basic formatting) to reduce failed submissions. The database still needs constraints for race conditions and alternate write paths, like two users submitting the same invoice number at the same time.

Don’t rely on UI-only rules, don’t make constraints stricter than real workflows, and don’t forget updates and status transitions. Also avoid letting users type IDs for relationships; use selectors and keep the database constraint as the backstop.

Model your data and constraints first in the Data Designer, then build the form and map constraint failures to friendly messages in your UI flow. In AppMaster, that usually means defining unique/check/FK rules in the model, wiring saves in the Business Process Editor, and keeping error text consistent across web and mobile; if you want to move fast, try building one high-impact form end-to-end and attempt to break it with messy sample data.