Data retention policies for business apps: windows and workflows

Learn how to design data retention policies for business apps with clear windows, archiving, and deletion or anonymization flows that keep reports useful.

What problem a retention policy actually solves

A retention policy is a clear set of rules your app follows about data: what you keep, how long you keep it, where it lives, and what happens when time is up. The goal isn’t to “delete everything.” It’s to keep what you need to operate the business and explain past events, while removing what you no longer need.

Without a plan, three problems show up fast. Storage grows quietly until it starts costing real money. Privacy and security risk rises with every extra copy of personal data. And reporting becomes unreliable when old records don’t match today’s logic, or when people delete things ad hoc and dashboards suddenly change.

A practical retention policy balances day-to-day operations, evidence, and customer protection:

- Operations: people can still do their work.

- Evidence: you can explain a transaction later.

- Customers: you don’t hold personal data longer than necessary.

Most business apps have the same broad data areas, even if they use different names: user profiles, transactions, audit trails, messages, and uploaded files.

A policy is part rules, part workflow, part tooling. The rule might say, “keep support tickets for 2 years.” The workflow defines what that means in practice: move older tickets to an archive area, anonymize customer fields, and record what happened. Tooling makes it repeatable and auditable.

If you build your app on AppMaster, treat retention as product behavior, not a one-off cleanup. Scheduled Business Processes can archive, delete, or anonymize data the same way every time, so reporting stays consistent and people trust the numbers.

Constraints to clarify before you pick any time windows

Before you set dates, get clear on why you’re keeping data at all. Retention decisions are usually shaped by privacy laws, customer contracts, and audit or tax rules. Skip this step and you’ll either keep too much (higher risk and cost) or delete something you later need.

Start by separating “must keep” from “nice to have.” Must-keep data often includes invoices, accounting entries, and audit logs needed to prove who did what and when. Nice-to-have data might be old chat transcripts, detailed click history, or raw event logs you only use for occasional analysis.

Requirements also change by country and industry. A support portal for a healthcare provider has very different constraints than a B2B admin tool. Even within one company, users in multiple countries can mean different rules for the same record type.

Write decisions in plain language and assign an owner. “We keep tickets for 24 months” is not enough. Define what’s included, what’s excluded, and what happens when the window ends (archive, anonymize, delete). Put a person or team in charge so updates don’t stall when products or laws change.

Get approvals early, before engineering builds anything. Legal confirms minimums and deletion obligations. Security confirms risk, access controls, and logging. Product confirms what users still need to see. Finance confirms recordkeeping needs.

Example: you might keep billing records for 7 years, keep tickets for 2 years, and anonymize user profile fields after account closure while keeping aggregated metrics. In AppMaster, those written rules can map cleanly to scheduled processes and role-based access, with less guesswork later.

Map your data by type, sensitivity, and where it lives

Retention policies fail when teams decide “keep it for 2 years” without knowing what “it” includes. Build a simple map of the data you have. Don’t aim for perfection. Aim for something a support lead and a finance lead can both understand.

Classify by type and sensitivity

A practical starting set:

- Customer data: profiles, tickets, orders, messages

- Employee data: HR records, access logs, device info

- Operational data: workflows, system events, audit logs

- Financial data: invoices, payouts, tax fields

- Content and files: uploads, exports, attachments

Then mark sensitivity in plain terms: personal data (name, email), financial (bank details, payment tokens), credentials (password hashes, API keys), or regulated data (for example, health information). If you’re unsure, label it “potentially sensitive” and treat it carefully until confirmed.

Map where it lives and who depends on it

“Where it lives” is usually more than your main database. Note the exact location: database tables, file storage, email/SMS logs, analytics tools, or data warehouses. Also note who relies on each dataset (support, sales, finance, leadership) and how often. That tells you what will break if you delete too aggressively.

A helpful habit: document the purpose of each dataset in one sentence. Example: “Support tickets are kept to resolve disputes and track response time trends.”

If you build with AppMaster, you can align this inventory with what’s actually deployed by reviewing your Data Designer models, file handling, and enabled integrations.

Once the map exists, retention becomes a series of small, clear choices instead of one big guess.

How to set retention windows people can follow

A window only works if it’s easy to explain and even easier to apply. Many teams do well with simple tiers that match how data is used: hot (used daily), warm (used sometimes), cold (kept for proof), then deleted or anonymized. The tiers turn an abstract policy into a routine.

Set windows by category, not one global number. Invoices and payment records usually need a long cold period for tax and audits. Support chat transcripts often lose value quickly.

Also decide what starts the clock. “Keep for 2 years” is meaningless unless you define “2 years from what.” Pick one trigger per category, such as creation date, last customer activity, ticket closure date, or account closure. If triggers vary without clear rules, people will guess and retention will drift.

Write exceptions up front so teams don’t improvise later. Common exceptions include legal hold, chargebacks, and fraud investigations. These should pause deletion. They shouldn’t lead to hidden copies.

Keep the final rules short and testable:

- Support chats: anonymize 6 months after the last message unless on legal hold

- Marketing leads: delete 12 months after last activity if no contract exists

- Customer accounts: delete 30 days after closure; keep invoices 7 years

- Security logs: keep 90 days hot, 12 months cold for investigations

- Any record flagged

legal_hold=true: do not delete until cleared

Archive strategies that keep data usable and cheaper

An archive is not a backup. Backups are for recovery after mistakes or outages. Archives are deliberate: older data leaves your hot tables and goes to cheaper storage, but stays available for audits, disputes, and historical questions.

Most apps need both. Backups are frequent and broad. Archives are selective and controlled, and you typically retrieve only what you need.

Choose storage that’s cheaper, but still searchable

Cheaper storage only helps if people can still find what they need. Many teams use a separate database or schema tuned for read-heavy queries, or export to files plus an index table for lookup. If your app is modeled around PostgreSQL (including in AppMaster), an “archive” schema or separate database can keep production tables fast while still allowing permitted reporting over archived data.

Before choosing format, define what “searchable” means in your business. Support might need lookup by email or ticket ID. Finance might need totals by month. Audits might need a trace by order ID.

Decide what to archive: full records or summaries

Full records preserve detail, but cost more and increase privacy risk. Summaries (monthly totals, counts, key status changes) are cheaper and often enough for reporting.

A practical approach:

- Archive full records for audit-critical objects (invoices, refunds, access logs)

- Archive summaries for high-volume events (clicks, page views, sensor pings)

- Keep a small reference slice in hot storage (often the last 30-90 days)

Plan index fields up front. Common ones include primary ID, user/customer ID, a date bucket (month), region, and status. Without these, archived data exists but is painful to retrieve.

Define restore rules too: who can request a restore, who approves it, where restored data lands, and expected timing. Restore can be slow on purpose if that reduces risk, but it needs to be predictable.

Deletion vs anonymization: choosing the right approach

Retention policies usually force a choice: delete records, or keep them while removing personal details. Both can be right, but they solve different problems.

A hard delete physically removes the record. It fits when you have no legal or business reason to keep the data and keeping it creates risk (for example, old chat transcripts with sensitive details).

A soft delete keeps the row but marks it as deleted (often with a deleted_at timestamp) and hides it from normal screens and APIs. Soft delete is useful when users expect restore, or when downstream systems might still reference the record. The downside is that soft-deleted data still exists, still consumes storage, and can still leak through exports if you’re not careful.

Anonymization keeps the event or transaction but removes or replaces anything that can identify a person. Done correctly, you can’t reverse it. Pseudonymization is different: you replace identifiers (like email) with a token but keep a separate mapping that can re-identify a person. That can help with fraud investigations, but it isn’t the same as being anonymous.

Be explicit about related data, because this is where policies break. Deleting a record but leaving attachments, thumbnails, caches, search indexes, or analytics copies can quietly defeat the whole point.

You also need proof that deletion happened. Keep a simple deletion receipt: what was removed or anonymized, when it ran, which workflow ran it, and whether it completed successfully. In AppMaster, that can be as simple as a Business Process writing an audit entry when the job finishes.

How to keep reporting value while removing personal data

Reports break when you delete or anonymize records your dashboards expect to join across time. Before changing anything, write down which numbers must remain comparable month to month. Otherwise you’ll be debugging “why did last year’s chart change?” after the fact.

Start with a short list of metrics that must stay accurate:

- Revenue and refunds by day, week, month

- Product usage: active users, event counts, feature adoption

- SLA metrics: response time, resolution time, uptime

- Funnel and conversion rates

- Support volume: tickets, categories, backlog age

Then redesign what you store for reporting so it doesn’t require personal identifiers. The safest approach is aggregation. Instead of keeping every raw row forever, keep daily totals, weekly cohorts, and counts that can’t be traced back to a person. For example, you can retain “tickets created per day per category” and “median first response time per week” even if you later remove original ticket content.

Keep stable analytics keys without keeping identities

Some reports still need a stable way to group behavior over time. Use a surrogate analytics key that isn’t directly identifiable (for example, a random UUID used only for analytics), and remove or lock down any mapping to the real user ID once the retention window ends.

Also separate operational tables from reporting tables when you can. Operational data changes and gets deleted. Reporting tables should be append-only snapshots or aggregates.

Define what changes after anonymization

Anonymization has consequences. Document what will change so teams aren’t surprised:

- User-level drill-down may stop after a certain date

- Historical segments may become “unknown” if attributes are removed

- Deduplication can change if you remove email or phone

- Some audits may still require non-personal timestamps and IDs

If you build in AppMaster, treat anonymization as a workflow: write aggregates first, verify report outputs, then anonymize fields in source records.

Step by step: implement the policy as real workflows

A retention policy works only when it becomes normal software behavior. Treat it like any other feature: define inputs, define actions, and make results visible.

Start with a one-page matrix. For each data type, record the retention window, the trigger, and what happens next (keep, archive, delete, anonymize). If people can’t explain it in a minute, it won’t be followed.

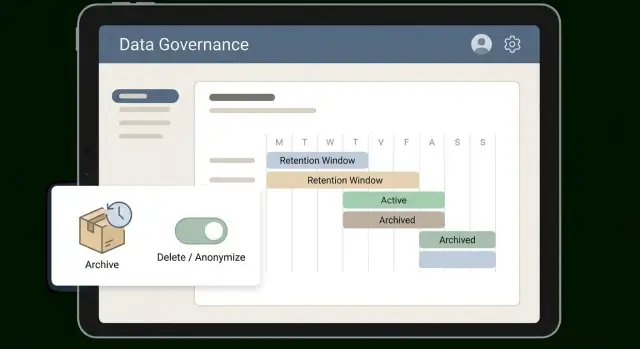

Add clear lifecycle states so records aren’t “mysteriously gone.” Most apps can get by with three: active, archived, and pending delete. Store the state on the record itself, not just in a spreadsheet.

A practical implementation sequence:

- Create the retention matrix and store it where product, legal, and ops can find it.

- Add lifecycle fields (status plus dates like

archived_atanddelete_after) and update screens and APIs to respect them. - Implement scheduled jobs (daily is common): one job archives, another purges or anonymizes what’s past the deadline.

- Add an exception path: who can pause deletion, for how long, and what reason must be recorded.

- Test on a production-like copy, then compare key reports (counts, totals, funnels) before and after.

Example: support tickets might stay active for 90 days, then move to archived for 18 months, then be anonymized. The workflow marks tickets archived, moves large attachments to cheaper storage, keeps ticket IDs and timestamps, and replaces names and emails with anonymous values.

In AppMaster, lifecycle states can live in the Data Designer, and archive/purge logic can run as scheduled Business Processes. The goal is repeatable runs with clear logs that are easy to audit.

Common mistakes that cause data loss or broken reports

Most retention failures aren’t about the chosen time window. They happen when deletion touches the wrong tables, misses related files, or changes keys that reports depend on.

A common scenario: a support team deletes “old tickets” but forgets attachments stored in a separate table or file store. Later, an auditor asks for evidence behind a refund. The ticket text exists, but the screenshots are gone.

Other common traps:

- Deleting a main record but leaving side tables (attachments, comments, audit logs) orphaned

- Purging raw events that finance, security, or compliance still needs to reconcile totals

- Relying on soft delete forever, so the database grows and deleted data still appears in exports

- Changing identifiers during anonymization (like

user_id) without updating dashboards, joins, and saved queries - Having no owner for exceptions and legal holds, so people bypass the rules

Another frequent break is reports built on person-based keys. Overwriting email and name is usually fine. Replacing the internal user ID can silently split one person’s history into multiple identities, and monthly active users or lifetime value reports will drift.

Two fixes help most teams. First, define reporting keys that never change (for example, an internal account ID) and keep them separate from personal fields that will be anonymized or deleted. Second, implement deletion as a complete workflow that walks all related data, including files and logs. In AppMaster, this often maps well to a Business Process that starts from a user or account, gathers dependencies, then deletes or anonymizes in a safe order.

Finally, decide who can pause deletion for legal holds and how that pause is recorded. If nobody owns exceptions, the policy will be applied inconsistently.

Quick checks before you turn anything on

Before you run deletion or archiving jobs, do a reality check. Most failures happen because nobody knows who owns the data, where copies are stored, or how reports depend on it.

A retention policy needs clear responsibility and a testable plan, not just a document.

Pre-launch checklist

- Assign an owner for every dataset (a person who can approve changes and answer questions).

- Confirm each data category has a retention window and a trigger (example: “90 days after ticket closes” or “2 years after last login”).

- Prove you can find the same record everywhere it appears: database, file storage, exports, logs, analytics copies, and backups.

- Verify archives stay useful: keep minimal fields for search and joins (IDs, dates, status) and document what gets dropped.

- Ensure you can produce evidence: what was deleted or anonymized, when it ran, and what rule it followed.

A simple validation is a dry run: take a small batch (like one customer’s old cases), run the workflow in a test environment, then compare key reports before and after.

What “evidence” should look like

Store proof in a way that doesn’t reintroduce personal data:

- Job run logs with timestamps, rule name, and record counts

- An immutable audit table with record IDs and the action taken (deleted or anonymized)

- A short exception list for items on legal hold

- A report snapshot showing the metrics you expect to stay stable

If you build on AppMaster, these checks map directly to implementation: retention fields in the Data Designer, scheduled jobs in the Business Process Editor, and clear audit outputs.

Example: a customer portal retention plan that still reports well

Picture a customer portal that stores support tickets, invoices and refunds, and raw activity logs (logins, page views, API calls). The goal is to reduce risk and storage cost without breaking billing, audits, or trend reporting.

Start by separating data you must keep from data you only use for day-to-day support.

A simple retention schedule could be:

- Support tickets: keep full content for 18 months after the ticket closes

- Invoices and payment records: keep for 7 years

- Raw activity logs: keep for 30 days

- Security audit events (admin changes, permission updates): keep for 12 months

Add an archive step for older tickets. Instead of keeping every message forever in main tables, move closed tickets older than 18 months into an archive area with a small searchable summary: ticket ID, dates, product area, tags, resolution code, and a short excerpt of the last agent note. That keeps context without keeping full personal detail.

For closed accounts, choose anonymization over deletion when you still need trends. Replace personal identifiers (name, email, address) with random tokens, but keep non-identifying fields like plan type and monthly totals. Store aggregated usage metrics (daily active user counts, tickets per month, revenue per month) in a separate reporting table that never stores personal data.

Monthly reporting will change, but it shouldn’t get worse if you plan for it:

- Ticket volume trends stay intact because they come from tags and resolution codes, not full text

- Revenue reporting stays stable because invoices remain

- Long-term usage trends can come from aggregates, not raw logs

- Cohorts can shift from identity to account-level tokens

In AppMaster, archive and anonymization steps can run as scheduled Business Processes, so the policy executes the same way every time.

Next steps: turn the policy into repeatable automation

A retention policy works when people can follow it and the system enforces it consistently. Start with a simple retention matrix: each dataset, owner, window, trigger, next action (archive, delete, anonymize), and sign-off. Review it with legal, security, finance, and the team that handles customer tickets.

Don’t automate everything at once. Pick one dataset end to end, ideally something common like support tickets or login logs. Make the workflow real, run it for a week, and confirm reporting matches what the business expects. Then expand to the next dataset using the same pattern.

Keep automation observable. Basic monitoring usually covers:

- Job failures (did archive or purge run and finish?)

- Archive growth (storage trend changes)

- Deletion backlog (items eligible but not processed)

- Report drift (key metrics changing after retention runs)

Plan the user-facing side too. Decide what users can request (export, deletion, correction), who approves it, and what the system does. Give support a short internal script: what data is affected, how long it takes, and what can’t be recovered after deletion.

If you want to implement this without writing custom code, AppMaster (appmaster.io) is a practical fit for retention automation because you can model lifecycle fields in the Data Designer and run scheduled archive and anonymization Business Processes with audit logging. Start with one dataset, make it boring and reliable, then repeat the pattern across the rest of the app.

FAQ

A retention policy prevents uncontrolled data growth and risky “just keep everything” habits. It sets predictable rules for what you keep, for how long, and what happens at the end so costs, privacy risk, and reporting surprises don’t creep in over time.

Start with why the data exists and who needs it: operations, audits/tax, and customer protection. Pick simple windows per data type (invoices, tickets, logs, files) and get early sign-off from legal, security, finance, and product so you don’t build workflows that later need to be undone.

Define one clear trigger per category, like ticket close date, last activity, or account closure. If the trigger is fuzzy, different teams will interpret it differently and retention will drift, which is how you end up with “2 years” meaning five different things in practice.

Use a legal hold flag or state that pauses archive/anonymization/deletion for specific records, and make the hold visible and auditable. The goal is to pause the normal workflow without creating hidden copies that nobody can track or explain later.

A backup is for disaster recovery and accidental mistakes, so it’s broad and frequent. An archive is a deliberate move of older data out of hot tables into cheaper, controlled storage that’s still retrievable for audits, disputes, and historical questions.

Delete when you truly have no reason to keep the data and it increases risk by existing at all. Anonymize when you still need the event or transaction for trends or proof but can remove personal fields permanently so it’s no longer tied to an individual.

Soft delete is useful for restore and for avoiding broken references, but it’s not real removal. Soft-deleted rows still take space and can leak into exports, analytics, or admin views unless every query and workflow consistently filters them out.

Protect reporting by storing long-term metrics as aggregates or snapshots that don’t depend on personal identifiers. If dashboards join on fields you plan to overwrite (like email), redesign the reporting model first so historical charts don’t change after retention runs.

Treat retention like a product feature: lifecycle fields on records, scheduled jobs to archive and then purge/anonymize, and audit entries that prove what happened. In AppMaster, this maps cleanly to Data Designer fields plus scheduled Business Processes that run the same way every time.

Do a small dry run on a test or production-like copy and compare key totals before and after. Also make sure you can trace a record across every place it exists (tables, file storage, exports, logs) and capture a deletion/anonymization receipt with timestamps, rule name, and counts.