CI/CD for Go backends: build, test, migrate, deploy

CI/CD for Go backends: practical pipeline steps for builds, tests, migrations, and safe deploys to Kubernetes or VMs with predictable environments.

Why CI/CD matters for Go backends you regenerate

Manual deployments fail in boring, repeatable ways. Someone builds on their laptop with a different Go version, forgets an environment variable, skips a migration, or restarts the wrong service. The release “works for me”, but not in production, and you only learn that after users feel it.

Generated code doesn’t remove the need for release discipline. When you regenerate a backend after updating requirements, you can introduce new endpoints, new data shapes, or new dependencies even if you never touched the code by hand. That’s exactly when you want a pipeline to act like a safety rail: every change goes through the same checks, every time.

Predictable environments mean your build and deploy steps run in conditions you can name and repeat. A few rules cover most of it:

- Pin versions (Go toolchain, base images, OS packages).

- Build once, deploy the same artifact everywhere.

- Keep config outside the binary (env vars or config files per environment).

- Use the same migration tool and process in every environment.

- Make rollbacks real: keep the previous artifact and know what happens to the database.

The point of CI/CD for Go backends isn’t automation for its own sake. It’s repeatable releases with less stress: regenerate, run the pipeline, and trust that what comes out is deployable.

If you use a generator like AppMaster that produces Go backends, this matters even more. Regeneration is a feature, but it only feels safe when the path from change to production is consistent, tested, and predictable.

Pick your runtime and define “predictable” upfront

“Predictable” means the same input produces the same result, no matter where you run it. For CI/CD for Go backends, that starts with agreeing on what must stay identical across dev, staging, and prod.

The usual non-negotiables are the Go version, your base OS image, build flags, and how configuration is loaded. If any of these change by environment, you get surprises like different TLS behavior, missing system packages, or bugs that only show up in production.

Most environment drift shows up in the same places:

- OS and system libraries (different distro versions, missing CA certs, timezone differences)

- Config values (feature flags, timeouts, allowed origins, external service URLs)

- Database shape and settings (migrations, extensions, collation, connection limits)

- Secrets handling (where they live, how they rotate, who can read them)

- Network assumptions (DNS, firewalls, service discovery)

Choosing between Kubernetes and VMs is less about what’s “best” and more about what your team can run calmly.

Kubernetes is a good fit when you need autoscaling, rolling updates, and a standard way to run many services. It also helps enforce consistency because pods run from the same images. VMs can be the right choice when you have one or a few services, a small team, and you want fewer moving parts.

You can keep the pipeline the same even if runtimes differ by standardizing the artifact and the contract around it. For example: always build the same container image in CI, run the same test steps, and publish the same migration bundle. Then only the deploy step changes: Kubernetes applies a new image tag, while VMs pull the image and restart a service.

A practical example: a team regenerates a Go backend from AppMaster and deploys to staging on Kubernetes but uses a VM in production for now. If both pull the exact same image and load config from the same kind of secret store, “different runtime” becomes a deployment detail, not a source of bugs. If you’re using AppMaster (appmaster.io), this model also fits well because you can deploy to managed cloud targets or export source code and run the same pipeline on your own infrastructure.

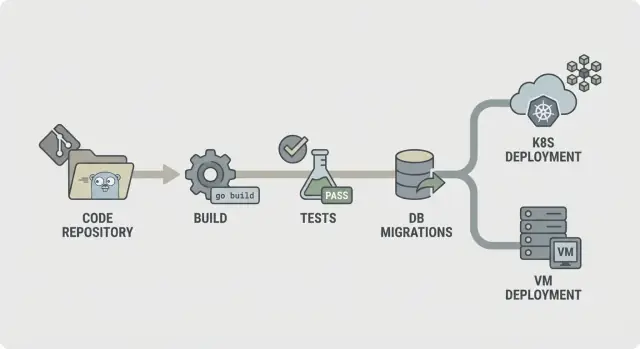

A simple pipeline map you can explain to anyone

A predictable pipeline is easy to describe: check the code, build it, prove it works, ship the exact thing you tested, then deploy it the same way every time. That clarity matters even more when your backend is regenerated (for example, from AppMaster), because changes can touch many files at once and you want fast, consistent feedback.

A straightforward CI/CD for Go backends flow looks like this:

- Lint and basic checks

- Build

- Unit tests

- Integration checks

- Package (immutable artifacts)

- Migrate (controlled step)

- Deploy

Structure it so failures stop early. If lint fails, nothing else should run. If build fails, you shouldn’t waste time starting databases for integration checks. This keeps costs down and makes the pipeline feel fast.

Not every step has to run on every commit. A common split is:

- Every commit/PR: lint, build, unit tests

- Main branch: integration checks, packaging

- Release tags: migrate, deploy

Decide what you keep as artifacts. Usually that’s the compiled binary or container image (the thing you deploy), plus migration logs and test reports. Keeping these makes rollbacks and audits simpler because you can point to exactly what was tested and promoted.

Step by step: build stage that is stable and repeatable

A build stage should answer one question: can we produce the same binary today, tomorrow, and on a different runner. If that isn’t true, every later step (tests, migrations, deploy) becomes harder to trust.

Start by pinning the environment. Use a fixed Go version (for example, 1.22.x) and a fixed runner image (Linux distro and package versions). Avoid “latest” tags. Small changes in libc, Git, or the Go toolchain can create “works on my machine” failures that are painful to debug.

Module caching helps, but only when you treat it as a speed boost, not a source of truth. Cache the Go build cache and module download cache, but key it by go.sum (or clear it on main when deps change) so new dependencies always trigger a clean download.

Add a fast gate before compilation. Keep it quick so developers don’t bypass it. A typical set is gofmt checks, go vet, and (if it stays fast) staticcheck. Also fail on missing or stale generated files, which is a common issue in regenerated codebases.

Compile in a reproducible way and embed version info. Flags like -trimpath help, and you can set -ldflags to inject commit SHA and build time. Produce a single named artifact per service. That makes it easy to trace what’s running in Kubernetes or on a VM, especially when your backend is regenerated.

Step by step: tests that catch issues before deploy

Tests only help if they run the same way every time. Aim for fast feedback first, then add deeper checks that still finish in a predictable time.

Start with unit tests on every commit. Set a hard timeout so a stuck test fails loudly instead of hanging the whole pipeline. Also decide what “enough” coverage means for your team. Coverage isn’t a trophy, but a minimum bar helps prevent slow quality drift.

A stable test stage usually includes:

- Run

go test ./...with a per-package timeout and a global job timeout. - Treat any test that hits the timeout as a real bug to fix, not “CI being flaky.”

- Set coverage expectations for critical packages (auth, billing, permissions), not necessarily the whole repo.

- Add the race detector for code that handles concurrency (queues, caches, fan-out workers).

The race detector is valuable, but it can slow builds a lot. A good compromise is to run it on pull requests and nightly builds, or only on selected packages, instead of every push.

Flaky tests should fail the build. If you must quarantine a test, keep it visible: move it to a separate job that still runs and reports red, and require an owner and deadline to fix it.

Store test output so debugging doesn’t require rerunning everything. Save raw logs plus a simple report (pass/fail, duration, and top slow tests). That makes it easier to spot regressions, especially when regenerated changes touch many files.

Integration checks with real dependencies, without slow builds

Unit tests tell you your code works in isolation. Integration checks tell you the whole service still behaves correctly when it boots, connects to real services, and handles real requests. This is the safety net that catches issues that only show up when everything is wired together.

Use ephemeral dependencies when your code needs them to start or to answer key requests. A temporary PostgreSQL (and Redis, if you use it) spun up just for the job is usually enough. Keep versions close to production, but don’t try to copy every production detail.

A good integration stage is small on purpose:

- Start the service with production-like env vars (but test secrets)

- Verify a health check (for example, /health returns 200)

- Call one or two critical endpoints and verify status codes and response shape

- Confirm it can reach PostgreSQL (and Redis if needed)

For API contract checks, focus on the endpoints that would hurt the most if they broke. You don’t need a full end-to-end suite. A few request/response truths are enough: required fields rejected with 400, auth required returns 401, and a happy-path request returns 200 with the expected JSON keys.

To keep integration tests fast enough to run often, cap the scope and control the clock. Prefer one database with a tiny dataset. Run only a few requests. Set hard timeouts so a stuck boot fails in seconds, not minutes.

If you regenerate your backend (for example with AppMaster), these checks pull extra weight. They confirm the regenerated service still starts cleanly and still speaks the API your web or mobile app expects.

Database migrations: safe ordering, gates, and rollback reality

Start by choosing where migrations run. Running them in CI is good for catching errors early, but CI usually shouldn’t touch production. Most teams run migrations during deploy (as a dedicated step) or as a separate “migrate” job that must finish before the new version starts.

A practical rule is: build and test in CI, then run migrations as close to production as possible, with production credentials and production-like limits. In Kubernetes, that’s often a one-off Job. On VMs, it can be a scripted command in the release step.

Ordering matters more than people expect. Use timestamped files (or sequential numbers) and enforce “apply in order, exactly once.” Make migrations idempotent where you can, so a retry doesn’t create duplicates or crash halfway through.

Keep the migration strategy simple:

- Prefer additive changes first (new tables/columns, nullable columns, new indexes).

- Deploy code that can handle both old and new schema for one release.

- Only then remove or tighten constraints (drop columns, make columns NOT NULL).

- Make long operations safe (for example, create indexes concurrently when supported).

Add a safety gate before anything runs. This can be a database lock so only one migration runs at a time, plus a policy like “no destructive changes without approval.” For example, fail the pipeline if a migration contains DROP TABLE or DROP COLUMN unless a manual gate is approved.

Rollback is the hard truth: many schema changes aren’t reversible. If you drop a column, you can’t bring the data back. Plan rollbacks around forward fixes: keep a down migration only when it’s truly safe, and rely on backups plus a forward migration when it isn’t.

Pair each migration with a recovery plan: what you do if it fails midway, and what you do if the app needs to roll back. If you generate Go backends (for example, with AppMaster), treat migrations as part of your release contract so regenerated code and schema stay in sync.

Packaging and configuration: artifacts you can trust

A pipeline only feels predictable when the thing you deploy is always the thing you tested. That comes down to packaging and configuration. Treat the build output as a sealed artifact and keep all environment differences outside of it.

Packaging usually means one of two paths. A container image is the default if you deploy to Kubernetes, because it pins the OS layer and makes rollouts consistent. A VM bundle can be just as reliable when you need VMs, as long as it includes the compiled binary plus the small set of files it needs at runtime (for example: CA certs, templates, or static assets), and you deploy it the same way every time.

Configuration should be external, not baked into the binary. Use environment variables for most settings (ports, DB host, feature flags). Use a config file only when values are long or structured, and keep it environment-specific. If you use a config service, treat it like a dependency: locked permissions, audit logs, and a clear fallback plan.

Secrets are the line you don’t cross. They don’t go in the repo, in the image, or in CI logs. Avoid printing connection strings on startup. Keep secrets in your CI secret store and inject them at deploy time.

To make artifacts traceable, bake identity into every build: tag artifacts with a version plus the commit hash, include build metadata (version, commit, build time) in an info endpoint, and record the artifact tag in your deployment log. Make it easy to answer “what is running” from one command or dashboard.

If you generate Go backends (for example with AppMaster), this discipline matters even more: regeneration is safe when your artifact naming and config rules make every release easy to reproduce.

Deploying to Kubernetes or VMs without surprises

Most deploy failures aren’t “bad code”. They’re mismatched environments: different config, missing secrets, or a service that starts but isn’t actually ready. The goal is simple: deploy the same artifact everywhere, and change only configuration.

Kubernetes: treat deploys as controlled rollouts

On Kubernetes, aim for a controlled rollout. Use rolling updates so you replace pods gradually, and add readiness and liveness checks so the platform knows when to send traffic and when to restart a stuck container. Resource requests and limits matter too, because a Go service that works on a big CI runner can get OOM-killed on a small node.

Keep config and secrets out of the image. Build one image per commit, then inject environment-specific settings at deploy time (ConfigMaps, Secrets, or your secret manager). That way, staging and production run the same bits.

VMs: systemd gives you most of what you need

If you deploy to virtual machines, systemd can be your “mini orchestrator”. Create a unit file with a clear working directory, environment file, and restart policy. Make logs predictable by sending stdout/stderr to your log collector or journald, so incidents don’t turn into SSH scavenger hunts.

You can still do safe rollouts without a cluster. A simple blue/green setup works: keep two directories (or two VMs), switch the load balancer, and keep the previous version ready for quick rollback. Canary is similar: send a small slice of traffic to the new version before committing.

Before marking a deploy “done”, run the same post-deploy smoke check everywhere:

- Confirm the health endpoint returns OK and dependencies are reachable

- Run a tiny real action (for example, create and read a test record)

- Verify the service version/build ID matches the commit

- If the check fails, roll back and alert

If you regenerate backends (for example, an AppMaster Go backend), this approach stays stable: build once, deploy the artifact, and let environment config drive the differences, not ad-hoc scripts.

Common mistakes that make pipelines unreliable

Most broken releases aren’t caused by “bad code”. They happen when the pipeline behaves differently from run to run. If you want CI/CD for Go backends to feel calm and predictable, watch out for these patterns.

Mistake patterns that cause surprise failures

Running database migrations automatically on every deploy with no guardrails is a classic. A migration that locks a table can take down a busy service. Put migrations behind an explicit step, require approval for production, and make sure you can safely re-run them.

Using latest tags or unpinned base images is another easy way to create mystery failures. Pin Docker images and Go versions so your build environment doesn’t drift.

Sharing one database across environments “temporarily” tends to become permanent, and it’s how test data leaks into staging and staging scripts hit production. Separate databases (and credentials) per environment, even if the schema is the same.

Missing health checks and readiness checks lets a deploy “succeed” while the service is broken, and traffic gets routed too early. Add checks that match real behavior: can the app start, connect to the database, and serve a request.

Finally, unclear ownership for secrets, config, and access turns releases into guesswork. Someone needs to own how secrets are created, rotated, and injected.

A realistic failure: a team merges a change, the pipeline deploys, and an automatic migration runs first. It completes in staging (small data), but times out in production (large data). With pinned images, environment separation, and a gated migration step, the deploy would have stopped safely.

If you generate Go backends (for example, with AppMaster), these rules matter even more because regeneration can touch many files at once. Predictable inputs and explicit gates keep “big” changes from turning into risky releases.

Quick checklist for a predictable CI/CD setup

Use this as a gut-check for CI/CD for Go backends. If you can answer each point with a clear “yes”, releases get easier.

- Lock the environment, not just the code. Pin the Go version and the build container image, and use the same setup locally and in CI.

- Make the pipeline run on 3 simple commands. One command builds, one runs tests, one produces the deployable artifact.

- Treat migrations like production code. Require logs for every migration run, and write down what “rollback” means for your app.

- Produce immutable artifacts you can trace. Build once, tag with the commit SHA, and promote through environments without rebuilding.

- Deploy with checks that fail fast. Add readiness/liveness health checks and a short smoke test that runs on every deploy.

Keep production access limited and auditable. CI should deploy using a dedicated service account, secrets should be managed centrally, and any manual production action should leave a clear trail (who, what, when).

A realistic example and next steps you can start this week

A small ops team of four ships once a week. They often regenerate their Go backend because the product team keeps refining workflows. Their goal is simple: fewer late-night fixes and releases that don’t surprise anyone.

A typical Friday change: they add a new field to customers (schema change) and update the API that writes it (code change). The pipeline treats these as one release. It builds one artifact, runs tests against that exact artifact, and only then applies migrations and deploys. That way, the database is never ahead of the code that expects it, and the code is never deployed without its matching schema.

When a schema change is included, the pipeline adds a safety gate. It checks that the migration is additive (like adding a nullable column) and flags risky actions (like dropping a column or rewriting a huge table). If the migration is risky, the release stops before production. The team either rewrites the migration to be safer or schedules a planned window.

If tests fail, nothing moves forward. The same is true if migrations fail in a pre-production environment. The pipeline shouldn’t try to push changes through “just this once.”

A simple set of next steps that works for most teams:

- Start with one environment (a single dev deploy you can reset safely).

- Make the pipeline always produce one versioned build artifact.

- Run migrations automatically in dev, but require approval in production.

- Add staging only after dev is stable for a few weeks.

- Add a production gate that requires green tests and a successful staging deploy.

If you’re generating backends with AppMaster, keep regeneration inside the same pipeline stages: regenerate, build, test, migrate in a safe environment, then deploy. Treat the generated source like any other source. Every release should be reproducible from a tagged version, with the same steps every time.

FAQ

Pin your Go version and your build environment so the same inputs always produce the same binary or image. That removes “works on my machine” differences and makes failures easier to reproduce and fix.

Regeneration can change endpoints, database models, and dependencies even if nobody edited code by hand. A pipeline makes those changes go through the same checks every time, so regenerating stays safe instead of risky.

Build once, then promote the exact same artifact through dev, staging, and prod. If you rebuild per environment, you can accidentally ship something you never tested, even if the commit is the same.

Run fast gates on every pull request: formatting, basic static checks, build, and unit tests with timeouts. Keep it quick enough that people don’t bypass it, and strict enough that broken changes stop early.

Use a small integration stage that boots the service with production-like config and talks to real dependencies like PostgreSQL. The goal is to catch “it compiles but won’t start” and obvious contract breaks without turning CI into an hours-long end-to-end suite.

Treat migrations as a controlled release step, not something that runs implicitly with every deploy. Run them with clear logs and a single-run lock, and be honest about rollback: many schema changes require forward fixes or backups, not a simple undo.

Use readiness checks so traffic only reaches new pods after the service is actually ready, and use liveness checks to restart stuck containers. Also set realistic resource requests and limits so a service that passes CI doesn’t get killed in production for using more memory than expected.

A simple systemd unit plus a consistent release script is often enough for calm deploys on VMs. Keep the same artifact model as containers when possible, and add a small post-deploy smoke check so a “successful restart” doesn’t hide a broken service.

Never bake secrets into the repo, build artifact, or logs. Inject secrets at deploy time from a managed secret store, limit who can read them, and make rotation a routine task rather than a fire drill.

Put regeneration inside the same pipeline stages as any other change: regenerate, build, test, package, then migrate and deploy with gates. If you’re using AppMaster to generate your Go backend, this lets you move fast without guessing what changed, and you can try the no-code flow to regenerate and ship more confidently.