Audit logging for internal tools: clean change history patterns

Audit logging for internal tools made practical: track who did what and when on every CRUD change, store diffs safely, and show an admin activity feed.

Why internal tools need audit logs (and where they usually fail)

Most teams add audit logs after something goes wrong. A customer disputes a change, a finance number shifts, or an auditor asks, "Who approved this?" If you only start then, you end up trying to reconstruct the past from partial clues: database timestamps, Slack messages, and guesswork.

For most internal apps, "good enough for compliance" doesn't mean a perfect forensic system. It means you can answer a small set of questions quickly and consistently: who made the change, what record was affected, what changed, when it happened, and where it came from (UI, import, API, automation). That clarity is what makes an audit log something people actually trust.

Where audit logs usually fail isn't the database. It's coverage. The history looks fine for simple edits, then gaps appear the moment work gets done at speed. The common offenders are bulk edits, imports, scheduled jobs, admin actions that bypass normal screens (like resetting passwords or changing roles), and deletes (especially hard deletes).

Another frequent failure is mixing up debugging logs with audit logs. Debug logs are built for developers: noisy, technical, and often inconsistent. Audit logs are built for accountability: consistent fields, clear wording, and a stable format you can show to non-engineers.

A practical example: a support manager changes a customer's plan, then an automation updates billing details later. If you only log "updated customer," you can't tell whether a person did it, a workflow did it, or an import overwrote it.

The audit log fields that answer who, what, when

Good audit logging starts with one goal: a person should be able to read one entry and understand what happened without guessing.

Who did it

Store a clear actor for every change. Most teams stop at "user id," but internal tools often change data through more than one door.

Include an actor type and actor identifier, so you can tell the difference between a staff member, a service account, or an external integration. If you have teams or tenants, also store the organization or workspace id so events never mix.

What happened and to which record

Capture the action (create, update, delete, restore) plus the target. "Target" should be both human-friendly and precise: table or entity name, record id, and ideally a short label (like an order number) for quick scanning.

A practical minimum set of fields:

- actor_type, actor_id (and actor_display_name if you have it)

- action and target_type, target_id

- happened_at_utc (timestamp stored in UTC)

- source (screen, endpoint, job, import) and ip_address (only if needed)

- reason (optional comment for sensitive changes)

When it happened

Store the timestamp in UTC. Always. Then display it in the viewer's local time in the admin UI. This avoids "two people saw different times" arguments during a review.

If you handle high-risk actions like role changes, refunds, or data exports, add a "reason" field. Even a short note like "Approved by manager in ticket 1842" can turn an audit trail from noise into evidence.

Pick a data model: event log vs versioned history

The first design choice is where the "truth" of change history lives. Most teams end up with one of two models: an append-only event log, or per-entity version history tables.

Option 1: Event log (append-only actions table)

An event log is a single table that records every action as a new row. Each row stores who did it, when it happened, what entity it touched, and a payload (often JSON) describing the change.

This model is straightforward to add and flexible when your data model evolves. It also maps naturally to an admin activity feed because the feed is basically "newest events first."

Option 2: Versioned history (per-entity versions)

A versioned history approach creates history tables per entity, like Order_history or User_versions, where every update creates a new full snapshot (or a structured set of changed fields) with a version number.

This makes point-in-time reporting easier ("what did this record look like last Tuesday?"). It can also feel clearer for auditors, because each record's timeline is self-contained.

A practical way to choose:

- Pick an event log if you want one place to search, easy activity feeds, and low friction when new entities appear.

- Pick versioned history if you need frequent record-level timelines, point-in-time views, or easy diffs per entity.

- If storage is a concern, event logs with field-level diffs are usually lighter than full snapshots.

- If reporting is the main goal, version tables can be simpler to query than parsing event payloads.

No matter which you pick, keep audit entries immutable: no updates, no deletes. If something was wrong, add a new entry that explains the correction.

Also consider adding a correlation_id (or operation id). One user action often triggers multiple changes (for example, "Deactivate user" updates the user, revokes sessions, and cancels pending tasks). A shared correlation id lets you group those rows into one readable operation.

Capture CRUD actions reliably (including deletes and bulk edits)

Reliable audit logging starts with one rule: every write goes through a single path that also writes an audit event. If some updates happen in a background job, an import, or a quick-edit screen that bypasses your normal save flow, your logs will have holes.

For creates, record the actor and the source (UI, API, import). Imports are where teams often lose the "who," so store an explicit "performed by" value even if the data came from a file or integration. It's also useful to store the initial values (either a full snapshot or a small set of key fields) so you can explain why a record exists.

Updates are trickier. You can log only the changed fields (small, readable, and fast), or store a full snapshot after each save (simple to query later, but heavy). A practical middle ground is to store diffs for normal edits and store snapshots only for sensitive objects (like permissions, bank details, or pricing rules).

Deletes should not erase evidence. Prefer a soft delete (an is_deleted flag plus an audit entry). If you must hard delete, write the audit event first and include a snapshot of the record so you can prove what was removed.

Treat undelete as its own action. "Restore" is not the same as "Update," and separating it makes reviews and compliance checks much easier.

For bulk edits, avoid a single vague entry like "updated 500 records." You need enough detail to answer "which records changed?" later. A practical pattern is a parent event plus per-record child events:

- Parent event: actor, tool/screen, filters used, and batch size

- Child event per record: record id, before/after (or changed fields), and outcome (success/fail)

- Optional: one shared reason field (policy update, cleanup, migration)

Example: a support lead bulk-closes 120 tickets. The parent entry captures the filter "status=open, older than 30 days," and each ticket gets a child entry showing status open -> closed.

Store what changed without creating a privacy or storage mess

Audit logs turn into junk fast when they either store too much (every full record, forever) or too little (just "edited user"). The goal is a record that is defensible for compliance and readable by an admin.

A practical default is to store a field-level diff for most updates. Save only the fields that changed, with "before" and "after" values. This keeps storage down and makes the activity feed easy to scan: "Status: Pending -> Approved" is clearer than a huge blob.

Keep full snapshots for the moments that matter: creates, deletes, and major workflow transitions. A snapshot is heavier, but it protects you when someone asks, "What exactly did the customer profile look like before it was removed?"

Sensitive data needs masking rules, or your audit table becomes a second database full of secrets. Common rules:

- Never store passwords, API tokens, or private keys (log "changed" only)

- Mask personal data like email/phone (store partial or hashed values)

- For notes or free-text fields, store a short preview and a "changed" flag

- Log references (user_id, order_id) instead of copying entire related objects

Schema changes can also break audit history. If a field later gets renamed or removed, store a safe fallback like "unknown field" plus the original field key. For deleted fields, keep the last known value but mark it as "field removed from schema" so the feed stays honest.

Finally, make entries human-friendly. Store display labels ("Assigned to") alongside raw keys ("assignee_id"), and format values (dates, currency, status names).

Step-by-step pattern: implement audit logging in your app flows

A reliable audit trail isn't about logging more. It's about using one repeatable pattern everywhere so you don't end up with gaps like "bulk import wasn't logged" or "mobile edits look anonymous."

1) Model the audit data once

Start in your data model and create a small set of tables that can describe any change.

Keep it simple: one table for the event, one for the changed fields, and a small actor context.

- audit_event: id, entity_type, entity_id, action (create/update/delete/restore), created_at, request_id

- audit_event_item: id, audit_event_id, field_name, old_value, new_value

- actor_context (or fields on audit_event): actor_type (user/system), actor_id, actor_email, ip, user_agent

2) Add one shared "Write + Audit" sub-process

Create a reusable sub-process that:

- Accepts the entity name, entity id, action, and the before/after values.

- Writes the business change to the main table.

- Creates an audit_event record.

- Computes changed fields and inserts audit_event_item rows.

The rule is strict: every write path must call this same sub-process. That includes UI buttons, API endpoints, scheduled automations, and integrations.

3) Generate actor and time on the server

Don't trust the browser for "who" and "when." Read the actor from your auth session, and generate timestamps server-side. If an automation runs, set actor_type to system and store the job name as the actor label.

4) Test with one concrete scenario

Pick a single record (like a customer ticket): create it, edit two fields (status and assignee), delete it, then restore it. Your audit feed should show five events, with two update items under the edit event, and the actor and timestamp populated the same way each time.

Build an admin activity feed that people can actually use

An audit log is only useful if someone can read it quickly during a review or an incident. The goal of the admin feed is simple: answer "what happened?" at a glance, then allow a deeper look without drowning people in raw JSON.

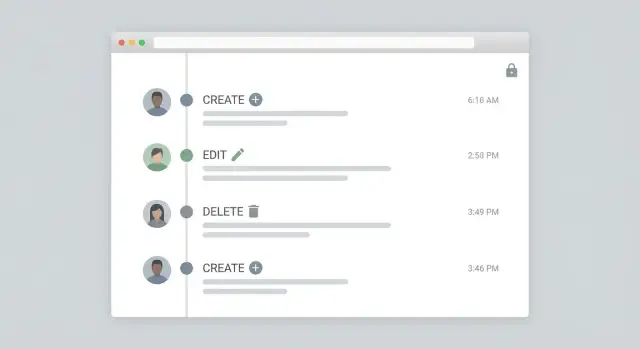

Start with a timeline layout: newest first, one row per event, and clear verbs like Created, Updated, Deleted, Restored. Each row should show the actor (person or system), the target (record type plus a human-friendly name), and the time.

A practical row format:

- Verb + object: "Updated Customer: Acme Co."

- Actor: "Maya (Support)" or "System: Nightly Sync"

- Time: absolute timestamp (with timezone)

- Change summary: "status: Pending -> Approved, limit: 5,000 -> 7,500"

- Tags: Updated, Deleted, Integration, Job

Keep "what changed" compact. Show 1-3 fields inline, then offer a drill-down panel (drawer/modal) that reveals full details: before/after values, request source (web, mobile, API), and any reason/comment field.

Filtering is what makes the feed usable after the first week. Focus on filters that match real questions:

- Actor (user or system)

- Object type (Customers, Orders, Permissions)

- Action type (Create/Update/Delete/Restore)

- Date range

- Text search (record name or ID)

Linking matters, but only when permitted. If the viewer has access to the affected record, show a "View record" action. If not, show a safe placeholder (for example, "Restricted record") while keeping the audit entry visible.

Make system actions obvious. Label scheduled jobs and integrations distinctly so admins can tell "Dana deleted it" from "Nightly billing sync updated it."

Permissions and privacy rules for audit data

Audit logs are evidence, but they're also sensitive data. Treat audit logging like a separate product inside your app: clear access rules, clear limits, and careful handling of personal info.

Decide who can see what. A common split is: system admins can view everything; department managers can view events for their team; record owners can view events tied to records they can already access (and nothing else). If you expose an activity feed, apply the same rules to every row, not just the screen.

Row-level visibility matters most in multi-tenant or cross-department tools. Your audit table should carry the same scoping keys as the business data (tenant_id, department_id, project_id), so you can filter consistently. Example: a support manager should see changes to tickets in their queue, but not salary adjustments in HR, even if both happen in the same app.

A simple policy that works in practice:

- Admin: full audit access across tenants and departments

- Manager: audit access limited by department_id or project_id

- Record owner: audit access only for records they can view

- Auditor/compliance: read-only access, export allowed, edits blocked

- Everyone else: no access by default

Privacy is the second half. Store enough to prove what happened, but avoid turning the log into a copy of your database. For sensitive fields (SSNs, medical notes, payment details), prefer redaction: record that the field changed without storing the old/new value. You can log "email changed" while masking the actual value, or store a hashed fingerprint for verification.

Keep security events separate from business record changes. Login attempts, MFA resets, API key creation, and role changes should go into a security_audit stream with tighter access and longer retention. Business edits (status updates, approvals, workflow changes) can live in a general audit stream.

When someone requests personal data removal, don't erase the whole audit trail. Instead:

- Delete or anonymize the user profile data

- Replace actor identifiers in logs with a stable pseudonym (for example, "deleted-user-123")

- Redact stored field values that are personal data

- Keep timestamps, action types, and record references for compliance

Retention, integrity, and performance for compliance

A useful audit log isn't just "we record events." For compliance, you need to prove three things: you kept the data long enough, it wasn't changed after the fact, and you can retrieve it quickly when someone asks.

Retention: decide a policy you can explain

Start with a simple rule that matches your risk. Many teams pick 90 days for day-to-day troubleshooting, 1 to 3 years for internal compliance, and longer only for regulated records. Write down what resets the clock (often: event time) and what gets excluded (for example, logs that include fields you should not keep).

If you have multiple environments, set different retention per environment. Production logs usually need the longest retention; test logs often don't need any.

Integrity: make tampering hard

Treat audit logs as append-only. Don't update rows, and don't allow normal admins to delete them. If a delete is truly required (legal request, data cleanup), record that action too as its own event.

A practical pattern:

- Only the server writes audit events, never the client

- No UPDATE/DELETE permissions on the audit table for regular roles

- A separate "break glass" role for rare purge actions

- A periodic export snapshot stored outside the main app database

Exports, performance, and monitoring

Auditors often ask for CSV or JSON. Plan an export that filters by date range and object type (like Invoice, User, Ticket) so you aren't hand-querying the database at the worst possible time.

For performance, index for how you search:

- created_at (time range queries)

- object_type + object_id (one record's full history)

- actor_id (who did what)

Watch for silent failure. If audit writing fails, you lose evidence and often won't notice. Add a simple alert: if the app processes writes but audit events drop to zero for a period, notify the owners and log the error loudly.

Common mistakes that make audit logs useless

The fastest way to waste time is to collect lots of rows that don't answer the real questions: who changed what, when, and from where.

One common trap is leaning on database triggers only. Triggers can record that a row changed, but they often miss the business context: which screen the user used, what request caused it, which role they had, and whether it was a normal edit or an automated rule.

Mistakes that most often break compliance and day-to-day usability:

- Recording full sensitive payloads (password resets, tokens, private notes) instead of a minimal diff and safe identifiers.

- Letting people edit or delete audit records "to correct" history.

- Forgetting non-UI write paths like CSV imports, integrations, and background jobs.

- Using inconsistent action names like "Updated," "Edit," "Change," "Modify," so the feed reads like noise.

- Logging only the object ID, without the human-friendly object name at the time of change (names change later).

Standardize your event vocabulary early (for example: user.created, user.updated, invoice.voided, access.granted) and require every write path to emit one event. Treat audit data as write-once: if someone made the wrong change, log a new correcting action rather than rewriting history.

Quick checklist and next steps

Before you call it done, run a few fast checks. A good audit log is boring in the best way: complete, consistent, and easy to read when something goes wrong.

Use this checklist in a test environment with realistic data:

- Every create, update, delete, restore, and bulk edit produces exactly one audit event per affected record (no gaps, no duplicates).

- Every event includes actor (user or system), timestamp (UTC), action, and a stable object reference (type + ID).

- The "what changed" view is readable: field names are clear, old/new values are shown, and sensitive fields are masked or summarized.

- Admins can filter the activity feed by time range, actor, action, and object, and they can export results for reviews.

- The log is hard to tamper with: write-only for most roles, and changes to the audit log itself are either blocked or separately audited.

If you're building internal tools with AppMaster (appmaster.io), one practical way to keep coverage high is to route UI actions, API endpoints, imports, and automations through the same Business Process pattern that writes both the data change and the audit event. That way, your CRUD audit trail stays consistent even as screens and workflows change.

Start small with one workflow that matters (tickets, approvals, billing changes), get the activity feed readable, then expand until every write path emits a predictable, searchable audit event.

FAQ

Add audit logs as soon as the tool can change real data. The first dispute or audit request usually happens before you think you’re “ready,” and backfilling history later is mostly guesswork.

A useful audit log can answer who did it, what record was touched, what changed, when it happened, and where it came from (UI, API, import, or job). If you can’t answer one of those quickly, the log won’t be trusted.

Debug logs are for developers and are often noisy and inconsistent. Audit logs are for accountability, so they need stable fields, clear wording, and a format that stays readable for non-engineers over time.

Coverage usually fails when changes happen outside the normal edit screen. Bulk edits, imports, scheduled jobs, admin shortcuts, and deletes are the common places where teams forget to emit audit events.

Store an actor type and an actor identifier, not just a user ID. That way you can clearly distinguish a staff member from a system job, service account, or external integration, and you can avoid “someone did it” ambiguity.

Store timestamps in UTC in the database, then display in the viewer’s local time in the admin UI. This prevents time zone disputes and makes exports consistent across teams and systems.

Use an append-only event log when you want one place to search and an easy activity feed. Use versioned history when you often need point-in-time views of a single record; in many apps, an event log with field-level diffs covers most needs with less storage.

Prefer soft deletes and log the delete action explicitly. If you must hard delete, write the audit event first and include a snapshot or key fields so you can prove what was removed later.

A practical default is to store field-level diffs for updates and snapshots for creates and deletes. For sensitive fields, record that a value changed without storing the secret itself, and redact or mask personal data so the audit log doesn’t become a second copy of your database.

Make one shared “write + audit” path and force every write to use it, including UI actions, API endpoints, imports, and background jobs. In AppMaster, teams often implement this as a reusable Business Process that performs the data change and writes the audit event in the same flow to avoid gaps.