سير العمل طويل الأمد: إعادة المحاولة، الرسائل الميتة، والرؤية

سير العمل طويل الأمد يمكن أن يفشل بطرق معقدة. تعرّف على أنماط الحالة الواضحة، عدادات المحاولات، التعامل مع الرسائل الميتة، ولوحات رؤية يمكن للمشغلين الوثوق بها.

What breaks in long-running automation

Long-running workflows fail differently than quick requests. A short API call either succeeds or errors right away. A workflow that runs for hours or days can get 9 steps out of 10 and still leave a mess: half-created records, confusing status, and no clear next action.

That’s why “it worked yesterday” comes up so often. The workflow didn’t change, but its environment did. Long-running workflows rely on other services staying healthy, credentials staying valid, and data staying in the shape the workflow expects.

The most common failure modes look like this: timeouts and slow dependencies (a partner API is up but takes 40 seconds today), partial updates (record A created, record B not created, and you can’t safely rerun), dependency outages (email/SMS providers, payment gateways, maintenance windows), lost callbacks and missed schedules (a webhook never arrives, a timer job didn’t fire), and human steps that stall (approval sits for days, then resumes with outdated assumptions).

The hard part is state. A “quick request” can keep state in memory until it finishes. A workflow can’t. It has to persist state between steps and be ready to resume after restarts, deploys, or crashes. It also has to cope with the same step triggering twice (retries, duplicate webhooks, operator replays).

In practice, “reliable” is less about never failing and more about being predictable, explainable, recoverable, and clearly owned.

Predictable means the workflow reacts the same way every time a dependency fails. Explainable means an operator can answer, in one minute, “Where is it stuck and why?” Recoverable means you can safely retry or continue without doing damage. Clear ownership means every stuck item has an obvious next action: wait, retry, fix data, or hand off to a person.

A simple example: an onboarding automation creates a customer record, provisions access, and sends a welcome message. If provisioning succeeds but messaging fails because the email provider is down, a reliable workflow records “Provisioned, message pending” and schedules a retry. It doesn’t rerun provisioning blindly.

Tools can make this easier by keeping workflow logic and persistent data close together. For example, AppMaster lets you model workflow state in your data (via the Data Designer) and update it from visual Business Processes. But the reliability comes from the pattern, not the tool: treat long-running automation as a series of durable states that can survive time, failures, and human intervention.

Define states that people can read

Long-running workflows tend to fail in repeatable ways: a third-party API slows down, a human hasn’t approved something, or a job is waiting behind a queue. Clear states make those situations obvious, so people don’t confuse “taking time” with “broken.”

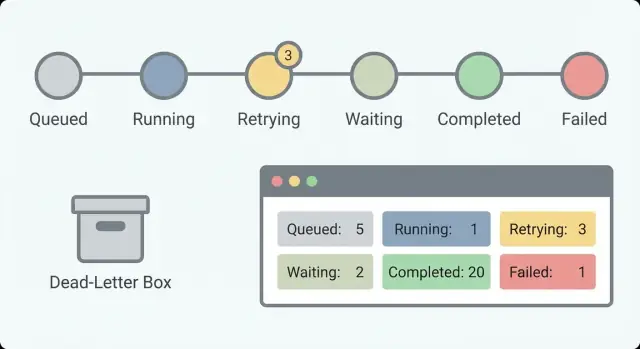

Start with a small set of states that answer one question: what is happening right now? If you have 30 states, nobody will remember them. With about 5 to 8, an on-call person can scan a list and understand it.

A practical state set that works for many workflows:

- Queued (created but not started)

- Running (actively doing work)

- Waiting (paused on a timer, callback, or human input)

- Succeeded (finished)

- Failed (stopped with an error)

Separating Waiting from Running matters. “Waiting for customer response” is healthy. “Running for 6 hours” might be a hang. Without this split, you’ll chase false alarms and miss real ones.

What to store with each state

A state name isn’t enough. Add a few fields that turn a status into something actionable:

- Current state and last state change time

- Previous state

- A short human-readable reason for failures or pauses

- An optional retry counter or attempt number

Example: an onboarding flow might show “Waiting” with the reason “Pending manager approval” and last changed “2 days ago.” That tells you it isn’t hung, but it might need a reminder.

Keep states stable

Treat state names like an API. If you rename them every month, dashboards, alerts, and support playbooks become misleading fast. If you need new meaning, consider introducing a new state and leaving the old one for existing records.

In AppMaster, you can model these states in the Data Designer and update them from Business Process logic. That keeps status visible and consistent across your app instead of buried in logs.

Retries that stop at the right time

Retries help until they hide the real problem. The goal isn’t “never fail.” The goal is “fail in a way people can understand and fix.” That starts with a clear rule for what’s retryable and what isn’t.

A rule most teams can live with: retry errors that are likely temporary (network timeouts, rate limits, brief third-party outages). Don’t retry errors that are clearly permanent (invalid input, missing permissions, “account closed,” “card declined”). If you can’t tell which bucket an error belongs to, treat it as non-retryable until you learn more.

Make retries step-scoped, not workflow-scoped

Track retry counters per step (or per external call), not just one counter for the whole workflow. A workflow can have ten steps, and only one might be flaky. Step-level counters keep a later step from “stealing” attempts from an earlier one.

For example, an “Upload document” call might be retried a few times, while “Send welcome email” shouldn’t keep retrying forever just because the upload used up attempts earlier.

Backoff, stop conditions, and clear next actions

Pick a backoff pattern that matches the risk. Fixed delays can be fine for simple, low-cost retries. Exponential backoff helps when you might be hitting rate limits. Add a cap so waits don’t grow without bounds, and add a little jitter to avoid retry storms.

Then decide when to stop. Good stop conditions are explicit: max attempts, max total time, or “give up for certain error codes.” A payment gateway returning “invalid card” should stop immediately even if you normally allow five attempts.

Operators also need to know what will happen next. Record the next retry time and the reason (for example, “Retry 3/5 at 14:32 due to timeout”). In AppMaster, you can store that on the workflow record so a dashboard can show “waiting until” without guessing.

A good retry policy leaves a trail: what failed, how many times it was tried, when it will try again, and when it will stop and hand off to dead-letter handling.

Idempotency and duplicate protection

In workflows that run for hours or days, retries are normal. The risk is repeating a step that already worked. Idempotency is the rule that makes this safe: a step is idempotent if running it twice has the same effect as running it once.

A classic failure: you charge a card, then the workflow crashes before it saves “payment succeeded.” On retry, it charges again. That’s a double-write problem: the outside world changed, but your workflow state didn’t.

The safest pattern is to create a stable idempotency key for each side-effecting step, send it with the external call, and store the step result as soon as you get it back. Many payment providers and webhook receivers support idempotency keys (for example, charging an order by OrderID). If the step repeats, the provider returns the original result instead of doing the action again.

Inside your workflow engine, assume every step can be replayed. In AppMaster, that often means saving step outputs in your database model and checking them in your Business Process before calling an integration again. If “Send welcome email” already has a MessageID recorded, a retry should reuse that record and move on.

A practical duplicate-safe approach:

- Generate an idempotency key per step using stable data (workflow ID + step name + business entity ID).

- Write a “step started” record before the external call.

- After success, store the response (transaction ID, message ID, status) and mark the step “done.”

- On retry, look up the stored result and reuse it instead of repeating the call.

- For uncertain cases, add a time window rule (for example, “if started and no result after 10 minutes, check provider status before retrying”).

Duplicates still happen, especially with inbound webhooks or when a user presses the same button twice. Decide the policy per event type: ignore exact duplicates (same idempotency key), merge compatible updates (like last-write-wins for a profile field), or flag for review when money or compliance risk is involved.

Dead-letter handling without losing context

A dead-letter is a workflow item that failed and was moved out of the normal path so it doesn’t block everything else. You keep it on purpose. The goal is to make it easy to understand what happened, decide whether it’s fixable, and reprocess it safely.

The biggest mistake is saving only an error message. When someone looks at the dead-letter later, they need enough context to reproduce the problem without guessing.

A useful dead-letter entry captures:

- Stable identifiers (customer ID, order ID, request ID, workflow instance ID)

- Original inputs (or a safe snapshot), plus key derived values

- Where it failed (step name, state, last successful step)

- Attempts (retry count, timestamps, next scheduled retry if any)

- Error details (message, code, stack trace if available, and dependency response payload)

Classification makes dead letters actionable. A short category helps operators choose the right next step. Common groups include permanent error (logic rule, invalid state), data issue (missing field, bad format), dependency down (timeout, rate limit, outage), and auth/permission (expired token, rejected credentials).

Reprocessing should be controlled. The point is to avoid repeated harm, like charging twice or spamming emails. Define rules for who can retry, when to retry, what can change (edit specific fields, attach a missing document, refresh a token), and what must stay fixed (request ID and downstream idempotency keys).

Make dead-letter items searchable by stable identifiers. When an operator can type “order 18422” and see the exact step, inputs, and attempt history, fixes become fast and consistent.

If you build this in AppMaster, treat the dead-letter as a first-class database model and store state, attempts, and identifiers as fields. That way your internal dashboard can query, filter, and trigger a controlled reprocess action.

Visibility that helps you diagnose issues

Long-running workflows can fail in slow, confusing ways: a step waits for an email reply, a payment provider times out, or a webhook arrives twice. If you can’t see what the workflow is doing right now, you end up guessing. Good visibility turns “it’s broken” into a clear answer: which workflow, which step, what state, and what to do next.

Start by making every step emit the same small set of fields so operators can scan quickly:

- Workflow ID (and tenant/customer if you have one)

- Step name and step version

- Current state (running, waiting, retrying, failed, completed)

- Duration (time in step and total time in workflow)

- Correlation IDs for external systems (payment ID, message ID, ticket ID)

Those fields support basic counters that show health at a glance. For long-running workflows, counts matter more than single errors because you’re looking for trends: work piling up, retries spiking, or waits that never end.

Track started, completed, failed, retrying, and waiting over time. A small waiting number can be normal (human approvals). A rising waiting count usually means something is blocked. A rising retrying count often points to a provider issue or a bug that keeps hitting the same error.

Alerts should match what operators experience. Instead of “error occurred,” alert on symptoms: a growing backlog (started minus completed keeps rising), too many workflows stuck in waiting beyond an expected time, high retry rate for a specific step, or a failure spike right after a release or config change.

Keep an event trail for every workflow so “what happened?” is answerable in one view. A useful trail includes timestamps, state transitions, summaries of inputs and outputs (not full sensitive payloads), and the reason for retries or failure. Example: “Charge card: retry 3/5, timeout from provider, next attempt in 10m.”

Correlation IDs are the glue. If a customer says “my payment was charged twice,” you need to connect your workflow events to the payment provider’s charge ID and your internal order ID. In AppMaster, you can standardize this in Business Process logic by generating and passing correlation IDs through API calls and messaging steps so the dashboard and logs line up.

Operator-friendly dashboards and actions

When a workflow runs for hours or days, failures are normal. What turns normal failures into outages is a dashboard that only says “Failed” and nothing else. The goal is to help an operator answer three questions quickly: what is happening, why it’s happening, and what they can safely do next.

Start with a workflow list that makes it easy to find the few items that matter. Filters reduce panic and chat noise because anyone can narrow the view quickly.

Useful filters include state, age (started time and time in current state), owner (team/customer/responsible operator), type (workflow name/version), and priority if you have customer-facing steps.

Next, show the “why” next to the status instead of hiding it in logs. A status pill only helps if it’s paired with the last error message, a short error category, and what the system plans to do next. Two fields do most of the work: last error and next retry time. If next retry is blank, make it obvious whether the workflow is waiting for a human, paused, or permanently failed.

Operator actions should be safe by default. Guide people toward low-risk actions first and make risky actions explicit:

- Retry now (uses the same retry rules)

- Pause/resume

- Cancel (with a required reason)

- Move to dead-letter

- Force continue (only if you can state what will be skipped and what might break)

“Force continue” is where most damage happens. If you offer it, spell out the risk in plain language: “This skips payment verification and may create an unpaid order.” Also show what data will be written if it proceeds.

Audit everything operators do. Record who did it, when, the before/after state, and the reason note. If you build internal tools in AppMaster, store this audit trail as a first-class table and show it on the workflow detail page so handoffs stay clean.

Step-by-step: a simple reliable workflow pattern

This pattern keeps workflows predictable: every item is always in a clear state, every failure has a place to go, and operators can act without guessing.

Step 1: Define states and allowed transitions. Write down a small set of states a person can understand (for example: Queued, Running, Waiting on external, Succeeded, Failed, Dead-letter). Then decide which moves are legal so work doesn’t drift into limbo.

Step 2: Break work into small steps with clear inputs and outputs. Each step should accept one well-defined input and produce one output (or a clear error). If you need a human decision or an external API call, make it its own step so it can pause and resume cleanly.

Step 3: Add a retry policy per step. Pick an attempt limit, a delay between tries, and stop reasons that should never retry (invalid data, permission denied, missing required fields). Store a retry counter per step so operators can see exactly what’s stuck.

Step 4: Persist progress after every step. After a step finishes, save the new state plus key outputs. If the process restarts, it should continue from the last completed step, not start over.

Step 5: Route to a dead-letter record and support reprocessing. When retries are exhausted, move the item to a dead-letter state and keep full context: inputs, last error, step name, attempt count, and timestamps. Reprocessing should be deliberate: fix data or config first, then re-queue from a specific step.

Step 6: Define dashboard fields and operator actions. A good dashboard answers “what failed, where, and what can I do next?” In AppMaster, you can build this as a simple admin web app backed by your workflow tables.

Key fields and actions to include:

- Current state and current step

- Retry count and next retry time

- Last error message (short) and error category

- “Re-run step” and “Re-queue workflow”

- “Send to dead-letter” and “Mark as resolved”

Example: onboarding workflow with a human approval step

Employee onboarding is a good stress test. It mixes approvals, external systems, and people who are offline. A simple flow might be: HR submits a new hire form, the manager approves, IT accounts are created, and the new hire gets a welcome message.

Make states readable. When someone opens the record, they should immediately see the difference between “Waiting for approval” and “Retrying account setup.” One line of clarity can save an hour of guesswork.

A clear set of states to show in the UI:

- Draft (HR is still editing)

- Waiting for manager approval

- Provisioning accounts (with retry counter)

- Notifying new hire

- Completed (or Canceled)

Retries belong on steps that depend on networks or third-party APIs. Account provisioning (email, SSO, Slack), sending email/SMS, and calling internal APIs are all good retry candidates. Keep the retry counter visible and cap it (for example, retry up to five times with increasing delays, then stop).

Dead-letter handling is for problems that won’t fix themselves: no manager on the form, invalid email address, or an access request that conflicts with policy. When you dead-letter a run, store context: which field failed validation, the last API response, and who can approve an override.

Operators should have a small set of straightforward actions: fix the data (add manager, correct email), re-run one failed step (not the whole workflow), or cancel cleanly (and undo partial setup if needed).

With AppMaster, you can model this in the Business Process Editor, keep retry counters in data, and build an operator screen in the web UI builder that shows state, last error, and a button to retry the failed step.

Checklist and next steps

Most reliability problems are predictable: a step runs twice, retries spin at 2 a.m., or a “stuck” item has no clue what happened last. A checklist keeps it from turning into guesswork.

Quick checks that catch most issues early:

- Can a non-technical person read every state and understand it (Waiting for payment, Sending email, Waiting for approval, Completed, Failed)?

- Are retries bounded with clear limits (max attempts, max time), and does each attempt increment a visible counter?

- Is progress saved after each step so a restart continues from the last confirmed point?

- Is every step idempotent, or protected against duplicates with a request key, lock, or “already done” check?

- When something goes to dead-letter, does it keep enough context to fix and re-run safely (input data, step name, timestamps, last error, and a controlled re-run action)?

If you can only improve one thing, improve visibility. Many “workflow bugs” are really “we can’t see what it’s doing” problems. Your dashboard should show what happened last, what will happen next, and when.

A practical operator view includes the current state, last error message, attempt count, next retry time, and one clear action (retry now, mark as resolved, or send to manual review). Keep actions safe by default: re-run a single step, not the whole workflow.

Next steps:

- Sketch your state model first (states, transitions, and which ones are terminal).

- Write retry rules per step: which errors retry, how long to wait, and when to stop.

- Decide how you’ll prevent duplicates: idempotency keys, unique constraints, or “check then act” guards.

- Define the dead-letter record schema so humans can diagnose and re-run confidently.

- Implement the flow and the operator dashboard in a tool like AppMaster, then test with forced failures (timeouts, bad inputs, third-party outages).

Treat this as a living checklist. Any time you add a new step, run these checks before it reaches production.

الأسئلة الشائعة

تستمر سير العمل طويل الأمد لساعات أو أيام، لذلك قد ينجح حتى النهاية أو يفشل متأخرًا بعد أن يحدث تغييرات جزئية. كما أنه يعتمد على عناصر قد تتغير أثناء التشغيل مثل توفر طرف ثالث، صلاحية بيانات الاعتماد، شكل البيانات، أو أوقات استجابة البشر.

اجعل مجموعة الحالات صغيرة وقابلة للقراءة حتى يفهمها المشغل بسرعة. إفتراضيًا مجموعة مثل queued، running، waiting، succeeded، failed تعمل جيدًا، مع فصل واضح بين “waiting” و“running” لتمييز الوقفات الصحية عن التجمّد الحقيقي.

خزن ما يكفي لجعل الحالة قابلة للعمل: الحالة الحالية، زمن آخر تغيير للحالة، الحالة السابقة، وسبب قصير عندما تكون في انتظار أو فشلت. إذا كانت هناك محاولات، فخزن أيضًا عدد المحاولات ووقت المحاولة المخطط التالي حتى لا يحتاج أحد للتخمين.

لأن ذلك يمنع الإنذارات الكاذبة والحوادث المفقودة. “بانتظار موافقة” أو “بانتظار ويب هوك” قد تكون صحية تمامًا، بينما “قيد التنفيذ لمدة ست ساعات” ربما يعني خطوة معلّقة؛ فصلهم يحسن الإنذارات وقرارات المشغل.

أعد المحاولات للأخطاء المحتملة مؤقتًا مثل انتهاء المهلة، حدود المعدل، أو انقطاعات قصيرة بمزود طرف ثالث. لا تعيد المحاولة للأخطاء الدائمة الواضحة مثل بيانات غير صالحة، أذونات مفقودة، أو رفض دفع، لأن التكرار يهدر الوقت وقد يسبب آثارًا جانبية متكررة.

تتبع المحاولات لكل خطوة بدلًا من عداد واحد لكل سير العمل. محاولات على مستوى الخطوة تمنع خطوة معطلة من استهلاك كل المحاولات المتاحة وتجعل التشخيص واضحًا: أي خطوة تفشل وكم مرة حاولت.

اختر تدرجًا يتناسب مع المخاطر، وضع حدًا حتى لا تنمو فترات الانتظار بلا حدود. اجعل قواعد الإيقاف صريحة — مثلاً حد أقصى لعدد المحاولات أو زمن إجمالي — وسجّل سبب الإيقاف والوقت التالي للمحاولة حتى يعرف الملاك ماذا يحدث.

افترض أن أي خطوة قد تُنفّذ مرتين. صمّمها بحيث لا تسبب ضررًا عند التكرار: أنشئ مفتاح idempotency ثابت لكل خطوة جانبية التأثير، سجّل “بدء الخطوة” قبل النداء الخارجي، وخزن النتيجة فور عودتها حتى يمكن إعادة استعمالها عند المحاولة التالية بدلاً من التكرار.

عنصر الرسائل الميتة هو عنصر نقلته خارج المسار العادي بعد استنفاد المحاولات حتى لا يعطل الباقي. خزّن سياقًا كافيًا لإصلاح المشكلة وإعادة المعالجة بأمان: معرفات ثابتة، المدخلات أو لقطة آمنة، أين فشل، تاريخ المحاولات، وتفاصيل خطأ التبعية، وليس رسالة غامضة فقط.

لوحة سريعة الاستخدام تُظهر أين هو العنصر، لماذا هناك، وماذا سيحصل لاحقًا. استخدم حقولًا ثابتة مثل معرف سير العمل، الخطوة الحالية، الحالة، زمن البقاء في الحالة، آخر خطأ، ومعرفات الترابط مع الأنظمة الخارجية. وفر إجراءات آمنة افتراضيًا مثل إعادة محاولة خطوة واحدة أو إيقاف/استئناف، ووسم الإجراءات الخطرة بوضوح.